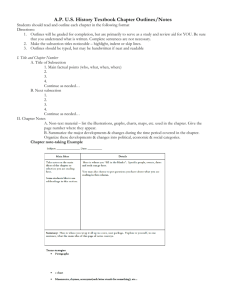

A Quarter Century in Partnerships

advertisement

A Quarter Century in Partnerships Peter E. McQuillan, FCA* P RÉCIS En 1971, la réforme fiscale a entraîné l’introduction de nouvelles notions et de nombreux changements dans la Loi de l’impôt sur le revenu. La notion de société de personnes est antérieure à la réforme fiscale, mais la Loi de l’impôt sur le revenu antérieure à 1972 ne contenait que huit mentions distinctes de la «société de personnes». Par conséquent, l’imposition des sociétés de personnes était essentiellement une question de procédure administrative. La mention la plus importante de la société de personnes dans la Loi de l’impôt sur le revenu antérieure à 1972 figurait à l’ancien alinéa 6(1)c) : «(…) doit être inclus dans le calcul du revenu d’un contribuable pour une année d’imposition (…) le revenu que le contribuable a tiré d’une société ou d’un syndicat pour l’année, qu’il l’ait touché ou non durant l’année». Lorsque cette phrase apparemment simple a été reportée dans la nouvelle Loi de l’impôt sur le revenu, avec application postérieure au 31 décembre 1971, elle est devenue une sous-section entière, soit la sous-section j. Cette sous-section, qui traitait des sociétés de personnes et de leurs associés, s’étendait des articles 96 à 103 et prévoyait un nombre impressionnant de règles et de règlements devant être pris en compte attentivement pour le calcul du revenu à la section B. Durant le quart de siècle depuis la réforme fiscale, le domaine des sociétés de personnes n’a pas fait l’objet d’une révision approfondie. Le ministère des Finances s’est concentré à contrer le transfert injustifié de certains types de déductions aux associés bénéficiaires. Cette longue bataille semble s’achever par suite de la présentation de nouvelles règles portant sur les dettes avec recours limité. Il est temps d’examiner certaines modifications législatives probantes visant à corriger nombre des lacunes susmentionnées, par exemple un cadre simple pour la fusion de sociétés de personnes; un transfert du surplus exonéré et du surplus imposable; la reconnaissance des sociétés de personnes comme des moyens appropriés de gels successoraux; l’élargissement de la notion de papillon aux sociétés de personnes; l’élimination du terme société de personnes de la définition de «bien étranger» lorsque ces sociétés de personnes comportent uniquement des biens canadiens; et la correction de certaines anomalies et lacunes au chapitre des roulements existants des sociétés de personnes. Au cours des dernières années, la notion de société à responsabilité limitée (SRL) a pris naissance aux États-Unis : les SRL sont reconnues * Of KPMG Peat Marwick Thorne, Toronto. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1465 1466 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE dans environ quatre cinquièmes des lois de divers États sur les sociétés de personnes. Pour l’application du droit des sociétés, une SRL offre la protection de la responsabilité limitée dont peuvent se prévaloir les sociétés par actions traditionnelles; dans le cadre de la fiscalité, elle offre le traitement de transfert normalement accordé à une société de personnes. Essentiellement, une SRL est une société de personnes constituée en société. Il est vrai que les avantages d’une SRL peuvent être comparés à ceux découlant de l’utilisation d’une société en commandite, mais une société en commandite constitue un moyen plus encombrant du point de vue de la loi et elle peut permettre à un créancier déterminé et bien financé de lever le voile sur la responsabilité limitée. Aucun examen du traitement fiscal des sociétés de personnes ne serait complet sans l’étude attentive des avantages que comporte l’adoption de la notion de SRL au Canada. ABSTRACT In 1971, tax reform introduced new concepts and many changes into the Income Tax Act. The concept of partnership predated tax reform, but the pre-1972 Income Tax Act contained a mere eight separate references to “partnership.” The taxation of partnerships, therefore, was essentially a matter of administrative procedure. The most important reference to “partnership” in the pre-1972 Income Tax Act was found in old paragraph 6(1)(c), which stated that “a taxpayer’s income from a partnership or syndicate for the year whether or not he has withdrawn it during the year shall be included in computing the income of a taxpayer for a taxation year.” When this seemingly straightforward sentence was carried into the new Income Tax Act for application after December 31, 1971, it occupied an entire subdivision, namely, subdivision j. That subdivision, which dealt with partnerships and their members, extended from sections 96 to 103 and set out an imposing array of rules and regulations that had to be carefully considered in the computation of income for division B. In the quarter century since tax reform was introduced, the partnership area has not undergone a thorough review. Finance’s focus has been to attack the unwarranted flowthrough of certain types of deductions to the receiving partners. This long war seems to be drawing to a close with the introduction of the new rules regarding limited recourse debt. The time has come to consider meaningful legislative changes to correct many of the deficiencies outlined above—for example, a simple framework for merging partnerships; a flowthrough of exempt surplus and taxable surplus; recognition of partnerships as appropriate vehicles for estate freezing; extension of the butterfly concept to partnerships; removal of partnerships from the definition of “foreign property” when those partnerships contain only Canadian assets; and correction of some of the anomalies and deficiencies in the existing partnership rollovers. In recent years, the concept of the limited liability corporation (LLC) has emerged in the United States: approximately four-fifths of the partnership acts of the various states now recognize LLCs. For corporate law (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1467 purposes, an LLC offers the protection of limited liability available to the classic limited corporation; for tax purposes, it offers the flowthrough treatment ordinarily accorded to a partnership: the LLC is, in essence, an incorporated partnership. It is true that the advantages of an LLC can be approximated with the use of a limited partnership, but a limited partnership is a more cumbersome vehicle at law and may permit the lifting of the veil of limited liability by a well-financed and determined creditor. No review of the tax treatment of partnerships would be complete without a careful consideration of the merits of adopting the concept of the LLC in Canada. THE TAX TREATMENT OF PARTNERSHIPS: AN OVERVIEW In Canada, as in many taxing jurisdictions, a partnership is generally not regarded as a separate person, but as a relationship between or among partners. Therefore, Canada generally adopts the lookthrough or “transparency” principle by taxing the income generated from the partnership’s activities in the hands of the partners rather than at the partnership level. While the partnership itself is not regarded as a taxable entity, the income and losses of the partnership are calculated “as if ” the partnership were a separate person. Certain exceptions to the transparency principle in Revenue Canada’s administrative treatment of partnerships are sometimes to the advantage and sometimes to the disadvantage of the taxpayer. The Income Tax Act1 does not define “partnership.” Although section 102 contains a definition of “Canadian partnership,” that definition presupposes the existence of a “partnership” and therefore gives little guidance as to what is considered a partnership for Canadian tax purposes. The definition of “Canadian partnership” requires that all the members be resident in Canada. There is no requirement, however, that all the partners be Canadian residents throughout the year. There is also no requirement that a Canadian partnership carry on all or any part of its business in Canada, or even that it be organized under Canadian law. The relevance of “Canadian partnership” is most apparent when one considers the accessibility of various rollovers for partnerships. Under Canadian law, the meaning of “partnership” is derived from the common law and from the provincial legislation under which partnerships are created. Partnership legislation is similar across the Canadian provinces; the exception is Quebec, where civil law, as opposed to common law, applies. Generally speaking, a partnership is an aggregation of its members whereby two or more persons carry on business in common with a view to profit. There must be an intention to earn a profit in order for Canadian courts to find that the parties are carrying on business through a partnership. The intention to form a partnership can be expressed in a 1 RSC 1985, c. 1 (5th Supp.), as amended (herein referred to as “the Act”). Unless otherwise stated, statutory references in this article are to the Act. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1468 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE written agreement or implied by the conduct of the parties. A partner can deal only with his or her partnership interests and not with the underlying partnership assets, because a partner is entitled only to his or her share of the net proceeds of the partnership property on a winding up of the partnership. Revenue Canada’s administrative position as to what constitutes a partnership is set out in Interpretation Bulletin IT -90.2 If a legal relationship is determined to be a partnership, it cannot, for certain other taxation purposes, be regarded as another legal structure. In no circumstances, therefore, will an enterprise that is at law organized as a partnership be recharacterized for tax purposes as a corporation (as is possible under US tax law). Conversely, Canada does not yet have “corporations” that may elect to be treated as flowthrough vehicles in the manner of a partnership: there is no direct Canadian equivalent of the US limited liability corporations. REPORTING REQUIREMENTS OF A PARTNERSHIP Because a partnership does not pay tax, it need not file a tax return. For many years after tax reform in 1971, there was no prescribed form or prescribed filing for partnerships. Surprisingly, and in contrast to the experience in the United States, not until 1989, under regulation 229, was a mandatory annual information return (T-5013) required to be filed by a partnership. Certain partnerships are still exempt from filing, as per Information Circular 89-5R3 (for example, partnerships with five or fewer members). Each member of a partnership with more than five members that either carries on business in Canada at any time during its fiscal period or meets the definition of a Canadian partnership is now required to file the annual information return on behalf of the partnership. In addition, a partnership must file supplementary information, including, inter alia, the allocation of the partnership income among each of the partners, the allocation of capital cost allowance, and the continuity of capital cost allowance as well as the continuity of the adjusted cost base of each of the partners. This information is also filed by the partnership on behalf of all the partners; a copy is then given to each partner. The partnership itself is given an identification number, and the partners file their supplementary slips from the partnership along with their tax returns. ROLLOVER PROVISIONS ADDED IN 1971 When tax reform dictated that a partnership was to compute its income as if it were a separate person, and when the concept of the taxation of capital gains was intoduced, an interest in a partnership became a separate and distinct capital property that could itself be subject to a capital gain or a capital loss. Attendant upon this concept was the need to introduce rules that would, in certain circumstances, allow assets to be transferred into or out of a partnership without a realization of gain upon the transfer. 2 Interpretation 3 Information Bulletin IT-90, “What Is a Partnership?” February 9, 1973. Circular 89-5R, “Partnership Information Return,” June 21, 1991. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1469 Subsections 85(2) and 85(3) allow a partnership to transfer its assets into a corporation on a tax-deferred basis in exchange for shares of the transferee corporation, and then allow the partnership to wind up and to distribute to each of the members of the partnership the shares that had been taken back by the partnership. Ordinarily, such a transfer of assets from a partnership to a corporation (with a subsequent windup of the partnership) could ordinarily be achieved on a tax-deferred basis. More important, subsection 97(2) allows the transfer of assets from a partner to the partnership on a tax-deferred basis. This is the partnership equivalent of the corporate rollover in subsection 85(1). In turn, subsection 98(3) allows the partnership to wind up and to distribute, pro rata, its assets to each partner on a tax-deferred basis. Subsection 98(5) permits one partner to buy out his or her other partners in such a manner that the surviving partner will have no immediate realization of his investment in the partnership; all of the former partners (the vending partners) will be deemed to have sold a capital interest in the partnership to the buying partner. Subsection 98(6) provides a continuation of a predecessor partnership by a new partnership when one or more partners withdrew from a predecessor partnership. Under the more common interpretation of subsection 98(6) and the administrative practice of Revenue Canada, this is the rollover that ensures a continuity of life to a predecessor Canadian partnership when the partnership agreement is silent, or even if it specifically provides for termination of the partnership on the death or withdrawal of one or more partners. By and large, these rollover provisions achieve the same results for partners and partnerships that are available to corporations and their shareholders in subdivision h of the Act. With one major exception, the partnership rollovers have remained substantially unchanged since their introduction in 1971. Technical anomalies have been corrected, and minor changes have been made to provide for certain transitory concepts (for example, the $100,000 lifetime capital gains exemption). However, no thorough review of these rollovers has been undertaken with a view to a complete technical amendment, and several necessary rollovers that would more consistently treat partnerships as favourably as corporations have not been added. This review is long overdue. The infamous MacEachen budget of November 12, 1981 contained a number of proposals that would have materially altered the conceptual application and availability of the partnership rollovers. These proposals significantly paralleled the proposals for changes in the corporate rollovers. Fortunately, the proposals were never implemented. The one major exception occurred on December 4, 1985, when the then minister of finance attacked the “Little Egypt” bump. It was recognized that the opportunity to bump inventory and depreciable capital property as well as non-depreciable capital property in the partnership area (subsections 98(3) and (5)) was far more generous than the equivalent bump in the corporate area (subsection 88(1)). Taxpayers that might otherwise have enjoyed only the corporate bump limited to non-depreciable (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1470 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE capital property arranged their affairs so that they could enjoy the more generous partnership bump even in a corporate context. The Department of Finance, which faced the alternative of expanding the categories of property that could be bumped in a corporate windup under section 88 or limiting the property that could be bumped under a partnership windup, was forced to act. Not surprisingly, Finance chose to narrow the bump in the partnership area rather than expand the bump in the corporate area. PRACTICAL ADDITIONS TO THE PARTNERSHIP PROVISIONS: LEGISLATING ADMINISTRATIVE PRACTICE In 1974, Finance added subsections 96(1.1) through 96(1.7) to the Act and thereby introduced as legislation what had previously existed as a commonsense administrative practice that allowed for the allocation of a share of income to retired partners. The subsections were a welcome addition to the Act, and by and large have remained significantly unaltered since their introduction. Similarly, sections 98.1 and 98.2 were added to the Act in 1974; they codified the administrative practice that had built up around the concept of a residual interest in a partnership. Because of the relieving nature of both these changes, their application was made retroactively effective to the 1972 taxation year. FINANCE’S WAR OF ATTRITION AGAINST CERTAIN PARTNERSHIPS Perhaps the most significant attribute of partnerships is their flowthrough nature, which clearly distinguishes a partnership from a corporation. If it is anticipated that the investment by the taxpayer will yield losses in the early stage of the investment, then a taxpayer may want to structure his affairs to ensure that the loss flows through to him and can be used by him against his other income during the period of those losses. As early as 1971, the Department of Finance recognized that there were certain kinds of property on which losses could not be flowed through a partnership to the partners. As a result, regulations 1100(11) and 1100(17) were introduced to ensure that capital cost allowance (CCA) could not be claimed by the partnership on certain kinds of capital assets—namely, rental properties and leasing properties—so as to create a net loss after CCA that could be passed on to the partners. Effective May 23, 1985, the rental property and leasing property regulations were expanded to limit CCA on certain fixed assets such as hotels and yachts (regulations 1100(14.1), (14.2), (17.2), and (17.3)). The war had begun! Taxpayers were desperate for tax shelters to be used to reduce their other income. On December 16, 1987, Finance introduced paragraphs 96(1)(e.1) and (g) and moved its attack away from the regulations and to the Act itself: in essence, it prevented the flowthrough of scientific research and experimental development (SR & ED) losses to passive members of a partnership. Under subsection 96(1), SR & ED losses could not be allocated to a “specified member” of a partnership, defined in section 248 to include any member of a partnership who was a limited partner and (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1471 any member of a partnership other than a member who was actively engaged in the activities of the partnership business. The war was escalating! After years of attempting to create by administrative fiat a framework of at-risk rules, a frustrated Department of Finance concluded that, for greater certainty, the at-risk rules had to be legislated. On February 25, 1986, a formal body of at-risk rules was introduced into the Act in subsections 96(2.1) through 96(2.7). Though the provisions were somewhat vague in their language, they were comprehensive, and their vague terms were intended always to be construed in favour of the taxing authorities. Interestingly, the at-risk rules initially were not to be applied to resource expenditures made by a partnership. Aggressive conduct by tax-shelter promoters made this exclusion short-lived. The aggressive interpretation of the concept of seismic expenditures compelled Finance to act, and act it did on June 17, 1987, when the at-risk rules were extended to the resource areas with the introduction of new section 66.8. Aggressive promoters were still looking for a loophole that could be used in a partnership context, and they turned their attention to accrued but unrealized losses dammed up in foreign partnerships. Canadian taxpayers could purchase an interest in the foreign partnership before those accrued losses were realized, and then be on hand at the end of the fiscal period of the partnership when the accrued losses were recognized in the partnership accounts. The recognized losses would then be allocated to the partners, including the Canadian partners who had bought their partnership interest months or days in advance of the loss recognition. In 1994 (but retroactive to December 21, 1992), subsection 96(8) was introduced; the subsection imposed a further limitation on the flowthrough of that type of loss to Canadian partners. Subsection 96(8) provides that, when a Canadian taxpayer acquires an interest in a foreign partnership that owns property with a fair market value less than its cost, the cost of inventory and of capital property and the capital cost of depreciable property of that partnership will be deemed to be the lesser of the fair market value at that time and its cost or capital cost otherwise determined. Thus Finance legislated against Canadians purchasing the “pregnant losses” of a foreign partnership. In December 1994, with the introduction of the concept of “limited recourse financing,” the minister of finance struck what may ultimately be the final blow against the use of partnerships to flow through undeserved tax deductions to investors. The result has been that, in addition to the perceived abusive arrangements, even certain bona fide arrangements may be attacked. New subparagraph 53(2)(c)(i.3) of the Act will provide for a decrease in the adjusted cost base of a taxpayer’s interest in a partnership to the extent of any limited recourse indebtedness of the taxpayer that can reasonably be considered to have been used to acquire the partnership interest. Paragraph 53(2)(c) is amended to exclude from its application partnership interests that are tax-sheltered investments, consequential on the introduction of new section 143.2. That section provides for the reduction of (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1472 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE the amount of certain expenditures of a taxpayer to the extent that a “limited recourse amount” can reasonably be considered to relate to the expenditure (for example, in respect of the taxpayer’s tax-sheltered investment). It seems that with this bodyguard of amendments Finance should now be satisfied that there will be no flowthrough of net losses or deductions to investors in partnerships in any manner that offends the department. OTHER AMENDMENTS TO THE PARTNERSHIP PROVISIONS In 1979, having recognized that taxpayers were using partnerships to increase their access to the small business deduction, Finance amended section 125 to introduce the concept of “specified partnership income,” thereby rendering the first $200,000 of active business income flowing through a partnership eligible for the small business deduction in the hands of corporate partners. This philosophy was arguably extended a little too far in 1988 with the addition of subsection 125(6.2): Notwithstanding any other provision of this section, where a corporation is a member of a partnership that was controlled, directly or indirectly in any manner whatever, by one or more non-resident persons, by one or more public corporations . . . or by any combination thereof at any time in its fiscal period ending in a taxation year of the corporation, the income of the partnership for that fiscal period from an active business carried on in Canada shall, for the purposes of computing the specified partnership income of a corporation for the year, be deemed to be nil [emphasis added]. In May 1985, in an effort to stimulate the funding of smaller Canadiancontrolled private corporations, the federal government introduced a number of financial intermediaries, which became eligible investments for the tax-deferred plans (registered pension plans, deferred profit-sharing plans, registered retirement savings plans, and registered retirement income funds). The May 1985 budget significantly increased the ability of the tax-deferred plans to invest directly and/or indirectly in the debt and equity securities of small businesses (especially private). The Act was changed to allow direct investment in certain qualifying securities of eligible corporations and indirect investment through new intermediaries defined in the Act. The new intermediaries included qualified limited partnerships (QLPs), small business investment corporations (SBICs), small business investment limited partnerships ( SBILPs), and small business investment trusts ( SBITs). Investment in SBICs, SBILPs, and SBIT s was even rewarded by the expansion of the tax-deferred plans’ foreign property limit from 10 percent to 30 percent (on the basis of three dollars of foreign property limit for each dollar invested). Unfortunately, the response to these new financial intermediaries has been lukewarm. Although a partnership interest ordinarily could be rolled over to a spouse in a tax-free transfer, when the adjusted cost base ( ACB) was negative at the time of the transfer it would be set to nil and the transferor would have a deemed capital gain equal to the amount of the negative ACB. Paragraph 70(6)(d.1) was added in 1994 (retroactive to dispositions made after January 15, 1987): the paragraph provides that, where the (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1473 property transferred is an interest in a partnership, the taxpayer will be treated, except for the purposes of paragraph 98(5)(g) of the Act, as not having disposed of the interest immediately before his death, and the transferee will be treated as having acquired the interest at its cost to the taxpayer. So that the transferee will be in the same position as the taxpayer, any amount added or deducted by the taxpayer under subsection 53(1) or 53(2) in respect of the partnership interest will be similarly added or deducted, as the case may be, in computing the transferee’s ACB of the interest. Subsection 100(2.1) was added on January 15, 1987. The subsection provides that when an amalgamation occurs after that date, the new corporation formed on the amalgamation acquires a predecessor corporation’s interest in a partnership. The predecessor is treated as having disposed of its interest in the partnership to the new corporation immediately before the amalgamation for proceeds of disposition equal to its ACB, and the new corporation is treated as having acquired the interest immediately after that time at a cost equal to the amount of such proceeds. As a result, the predecessor corporation will be required to recognize a gain on disposition of any interest in the partnership that has a negative ACB. As a result of this amendment, it is now necessary to calculate the ACB of any partnership interest held by a corporation prior to any amalgamation. It is very easy for a partnership interest to be positive for accounting purposes but negative for tax purposes (since draws reduce ACB when made, but accruing profits do not enter the ACB until the year-end of the partnership). Note that the application of subsection 100(2.1) is narrowed to situations in which the new corporation formed on amalgamation acquires the interest in the partnership from the predecessor corporation to which it was not related. Subsection 251(3.1) treats the new corporation as related to any predecessor corporation to which it would have been related immediately before the amalgamation if the new corporation had been in existence at that time. Before the enactment of subsection 100(2.1), it had been argued that (except for Quebec income tax purposes), when a corporation holding a partnership interest with a negative ACB amalgamated, the ACB was set to nil in the amalgamated company without the predecessor’s having to recognize the gain—obviously an anomalous and undeserved result. ELIMINATING THE TAX DEFERRAL ENJOYED BY INDIVIDUALS IN A PARTNERSHIP Individuals who have carried on business either as a proprietorship or as a partnership have been able to defer the payment of tax on business income by selecting a business year that ends before December 31. For example, if an individual started a business in a partnership on February 1, 19-1, he could select as his first year-end January 31, 19-2. In his personal tax return for the calendar year ending December 31, 19-1, he would have no income from this partnership business to report (or on which to pay tax) for the period from January 1, 19-1 to December 31, 19-1. The income for the 11 months in 19-1 (from February 1, 19-1 to (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1474 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE December 31, 19-1) would be recognized in the fiscal year ending January 31, 19-2, and reported in a personal return for the calendar year ending December 31, 19-2. The February 27, 1995 budget proposes to eliminate this deferral opportunity for all individuals (that is, proprietorships), professional corporations conducting the practice of the six designated professions, and partnerships any member of which is a person described above. These taxpayers will be required to report their income on a calendar-year basis for fiscal years beginning after 1994 (or, alternatively, to retain a January year-end but to pay tax on their income on a calendar-year basis). Transitional relief is proposed that will provide for the inclusion of the deferred income over a 10-year period: 5 percent in 1995, 10 percent in each year from 1996 to 2003, and 15 percent in 2004. Individuals affected by these rules will be able to file their personal tax returns on June 15 instead of April 30, but will nevertheless be required to pay any balance of tax owing by April 30. Finance has been clever enough and reasonable enough to introduce this harsh provision with a generous 10-year transitional rule. DEFICIENCIES IN THE CURRENT LAW A Merger of Partnerships: The Missing Rollover In both the corporate and the partnership sections of the Act, a number of rollover provisions permit a reorganization to take place without triggering tax consequences. Unfortunately, since tax reform in 1971, no rollover provision has dealt directly with a tax-free merger or combination of partnerships. Since 1971 it has been generally necessary to use two separate partnership rollovers, neither of which at first glance appears to be the most logical way to merge two partnerships. Taxpayers deserve a partnership equivalent to the amalgamation provisions in section 87. It should be possible simply to aggregate two partnerships on a tax-free basis in such a manner that the combined partnership will have all the tax attributes of the two predecessors. The two partnership rollovers are found in subsections 97(2) and 98(3). (Note that these two rollovers apply only to Canadian partnerships.) Merger of a partnership by way of subsection 97(2) and subsection 98(3) requires a careful navigation of the two provisions to ensure that problems do not arise. For example, paragraph 13(7)(e) does not intervene when a nonarm’s-length partner transfers depreciable capital property. Careful and sometimes artificial restucturing is required to ensure that 1) the half-year rule regarding the acquisition of depreciable capital property does not intervene; 2) leasehold interests are not subjected to a longer than necessary period of amortization; 3) there are no traps in merging principal business real estate partnerships; and 4) the reserve accounts in paragraphs 20(1)(m) and (n) and the instalment sale reserve in paragraph 40(1)(a) are not unreasonably run off. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1475 Lack of Flowthrough of Exempt Surplus and Taxable Surplus Pots Through a Domestic Partnership Revenue Canada has indicated that where a Canadian partnership holds shares of a foreign corporation that meets the definition of a foreign affiliate, then the foreign corporation is a foreign affiliate of the partnership and not the partners. Revenue Canada argues that, for the purposes of computing the income of the partners, the partnership owns the shares of the foreign corporation. Therefore, in determining the relationship to the foreign affiliate, the partnership is considered a separate person. If the partnership holds an investment in a corporation that constitutes a foreign affiliate of the partnership, and if that foreign affiliate is also a controlled foreign affiliate of the partnership, the partnership will include in its income its share of any foreign accrual property income, and it will retain its character when allocated to the partners. However, Revenue Canada takes the somewhat debatable position that, regardless of a partner’s direct or indirect ownership of a partnership that holds shares of a foreign affiliate, “exempt surplus” and “taxable surplus” will not retain their character when passing through a partnership to Canadian partners that are corporations, because the foreign corporation is not a foreign affiliate of the Canadian corporate partners. Tax Treaty Entitlement of Foreign Partnerships When the applicable treaty recognizes that a foreign partnership is a “resident” of the other state because partnerships are treated in that state as taxable entities, the partnership itself ordinarily would be entitled to treaty benefit, according to the OECD model.4 In the light of section 6.2 of the Income Tax Conventions Interpretations Act, 5 however, it appears that Canada will view the foreign partnership as entitled to the tax treaty benefits in respect of non-resident partners only if none of the partners is resident in Canada. If the treaty in question does not refer to a partnership as a person, Canada will view each of the foreign partners as having received his proportionate share of Canadian source income directly and will afford the tax treaty benefits accordingly. If some or all of the partners of the foreign partnership are residents of a third state, Canada will apply the tax treaty with the country in which the partnership was established if the foreign partnership is recognized as a person for the purposes of that treaty. In any other case, the relevant treaty will be between Canada and the country in which the partners themselves are resident. If no treaty is in force with this third state, Canada, as the state of source, will levy the full 25 percent withholding tax under part XIII of the Act on any passive income paid to the partnership. If the foreign partnership were carrying on business in Canada, the partners resident in the 4 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital (Paris: OECD) (looseleaf ). 5 RSC 1985, c. I-4, as amended. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1476 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE third state would have to include the full amount of their pro rata share of the income from business sourced in Canada and would not be able to claim the deduction for treaty-protected income under paragraph 110(1)(f ) of the Act. Note that section 6.2 of the Income Tax Conventions Interpretations Act was added by Canada to ensure that the principles enunciated in the United Kingdom in Padmore 6 were not extended to Canadian treaty interpretation. The application of section 6.2 of the Income Tax Conventions Interpretations Act may be retroactive. Allocation of a Partnership’s Income or Loss to Partners Who Acquire or Dispose of Their Partnership Interest During the Partnership’s Fiscal Year Subsection 96(1) of the Act requires a partnership to calculate the income or loss from any source for its fiscal period and to allocate such income or loss to its partners. Administratively, Revenue Canada permits the allocation of income or loss to partners even if they have not been partners throughout the fiscal period of the partnership. Thus, partners may leave or enter a partnership part way through a year, and all partners, both part-year partners and former partners, will be allowed an allocation of income and expense. This administrative practice should be clarified in the legislation. Furthermore, if one partner exits a partnership part way through the year and another partner enters, it is important that there be agreement between the two parties as to how income is to be reckoned for allocation purposes for the part year. It is also important to remember that income or loss reckoned on a tax basis may be significantly different from the income or loss reckoned on an accounting basis: the agreement should be clear as to exactly how income is to be reckoned. Similarly, it is important to recognize that, in reckoning a partner’s ACB, drawings made at any time during the year reduce the partner’s adjusted cost base, while income earned is not allocated to the partner for inclusion in this cost base until the end of the fiscal period. To the extent that an interest in a partnership is being rolled over at any time other than the fiscal period of the partnership, it is important to recognize that the ACB requires careful attention in establishing the values to be used in the election. Participating and Shared Appreciation Debt Obligations: Do They Constitute a Partnership Interest? Until recently, both lenders and borrowers were able to use participating debt instruments in such a manner as to optimize their tax positions. A borrower who sought to deduct the fixed and variable financing charges on an as-incurred basis would argue that there had been no disruption of its principal business status. A lender, frequently a non-resident, would argue that fixed and variable finance income was income (other than interest) not earned from carrying on business in Canada through a permanent establishment, and that it was deductible but not subject to withholding tax or branch tax. Two amendments to the Act have affected the use of 6 Padmore v. IR Commrs., [1989] BTC 221 (CA). (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1477 participating debt instruments. Paragraph 20(1)(e) has been amended so that, to the extent that an amount was previously deductible immediately under old paragraph 20(1)(e), it is no longer deductible immediately but must be amortized over the period referred to therein (frequently, evenly over five years). This amendment may render these instruments decidedly less attractive to the borrower. Paragraph 212(1)(b) has been amended to render both fixed and variable participation payments subject to a withholding tax that does not escape under subparagraph 212(1)(b)(vii). Revenue Canada has been prepared to rule on the tax nature of a debt instrument that contains fixed and variable payments, but only when the yield, both fixed and variable, offered by the instrument approximates a reasonable return similar to that of straight debt. The debt instrument should therefore be thoroughly analyzed to determine whether it includes positive (as well as negative) covenants that in themselves constitute continual management decision making, which, if exercised, could constitute partnership. Is the income participation calculated on gross revenues or net revenues? (A net revenue participation has more of the attributes of partnership.) Does the debt holder share in losses? In the loss year, is the fixed interest still payable? Is it cumulative? If the holder of the participating instrument is deemed to hold a partnership interest, it may, under subsection 206(1), be “foreign property” to an exempt tax-deferred plan. In addition, the partnership may cease to be a principal business partnership if one of the new partners is not itself a principal business corporation. Participating and shared appreciation debt obligations may be recharacterizable as a partnership interest. The Interaction of Subsection 129(6) and Partnerships with Corporate Partners: The Norco Development Case The issue of the payment of amounts by a corporate partnership to one of the corporations associated with the corporate partners was considered in Norco Development Ltd. v. The Queen.7 Norco Development was a corporate member of a partnership. It was associated with a corporation, Noort Brothers Construction Limited, which was not a member of the partnership. Noort loaned funds to the partnership at interest. The interest received by Noort was treated by it as Canadian investment income. Revenue Canada reassessed Noort and included the interest in its active business income pursuant to subsection 129(6). The minister of revenue argued and the court agreed that the payment of interest was in essence made by the corporate partners to the recipient, and therefore within the ambit of subsection 129(6). In support of this proposition, the minister reviewed case law, which had the effect of piercing the partnership veil and causing the payments of interest to be viewed as being from one corporation to another. The effect of this decision may be far more widespread than is apparent on the surface. In essence, the conclusion to 7 85 DTC 5213 (FCTD). (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1478 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE be drawn from this case is that amounts paid to or by a partnership are to be treated as if they were paid to or by the individual partners. However, it is not yet completely clear how the Norco decision should be applied in practice. In Norco, the facts were straightforward: all the members of the partnership were associated with each other, and all were associated with the corporation to which the interest was paid by the partnership. But how will Norco be applied if a 30 percent minority corporate partner in a partnership with no other corporate partner is associated with a corporation to which interest and/or rents are paid by the partnership? Is 0 percent of the interest and/or rent deemed by Norco to be active business income pursuant to subsection 129(6)? If a 60 percent majority corporate partner is associated with a corporation to which interest and/or rents are paid by the partnership, then it seems that, pursuant to Norco, 100 percent of the interest and/or rent would be deemed to be active business income pursuant to subsection 129(6). In Norco, the minister of revenue argued and the court agreed that the payments were in essence made by the corporate partners to the recipient; it is therefore surprising when the policy behind this decision is transposed to a partnership that has borrowed money from a specified non-resident. Consider the case of a corporate partnership in which one of the corporate partners is a foreign-controlled corporation that perhaps controls the partnership. If the partnership itself borrows significantly from the parent company of the foreign-controlled Canadian corporate partner, the rationale in Norco seems to suggest that the interest-bearing indebtedness will be tested against the thin capitalization provisions in subsection 18(4) as if the loan had been made directly from the specified non-resident to its Canadian subsidiary corporation. Surprisingly, the rationale in Norco does not seem to be applied even by Revenue Canada to this particular fact pattern. Revenue Canada has commented several times at its round tables that such a loan from a specified non-resident will not be subject to any test of thin capitalization, since a partnership itself is not directly subject to the thin capitalization rules in subsection 18(4). While this particular interpretation may be lenient and readily accepted by taxpayers, it appears inconsistent with the rationale established by Revenue Canada in Norco. Permanent Establishments of Partnerships: Compliance Issues for Partners Certain partnership arrangements may cause partners to have permanent establishments in more than one province. Prospective investors in partnerships should be aware of two important points: 1) A partnership must allocate its business income to each of the provinces or countries in which it operates through a permanent establishment. Partners, both individuals and corporations, will become liable to income tax and certain other provincial taxes in those provinces with permanent establishments. The rules for recognition of income and the writing off of various expenses may vary among the provinces. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1479 2) On a number of occasions, partnerships of professionals have asked the Department of Finance to simplify the filing of personal tax returns by the individual members. While Finance has been sympathetic to the initial submissions, it has asked the various professions to determine whether all of the members of the partnerships will be satisfied to simply file and pay tax in their province of residence. Finance’s suggestion has not been met with universal acceptance by members of the professions, and as a result individual taxpayers (as well as corporations) remain subject to tax in each of the provinces in which they have a permanent establishment. Estate Freezes Using Partnerships The concept of using a corporation to achieve a freeze in the value of an individual’s estate is well understood. That understanding flows from a continuing series of interpretation bulletins issued by Revenue Canada, especially those dealing with the attributes of the share consideration that must be taken back by the freezor in the classic estate freeze plan. The rationale could easily be transposed to freezing in the context of a partnership interest, where the freezor was prepared to take back a capital interest in a partnership that was entitled to a fixed priority return on the freezor’s capital interest in the assets of the estate. For some reason, Revenue Canada has been completely reluctant to allow the use of partnerships to achieve the kind of estate freeze attainable through a corporation. Revenue Canada has on several occasions indicated that if a party were to attempt an estate freeze using a partnership rather than a corporation, the freeze might well be challenged under section 103 of the Act on the basis that the allocation of income from the partnership was not reasonable. It is unclear from a policy point of view why Revenue Canada has been so reluctant to see partnerships used for estate freezing. It is not obvious that the economic results and the attendant tax results would be any less favourable to Revenue Canada because of the use of a partnership rather than a corporation. Immigration to Canada and Emigration from Canada If a partnership is not carrying on business in Canada, but a member of the partnership becomes a resident of Canada during the fiscal year of the partnership, the individual will be taxed under part I for his or her share of the income of the partnership for the entire fiscal period of the partnership that ends after the partner becomes a resident of Canada. While this interpretation may be debatable, it is Revenue Canada’s view that there is no basis for prorating the partnership income for periods before and after the partner becomes a resident of Canada. The transfer to Canada does not in itself cause a year-end in the partnership unless there are unusual clauses in the partnership agreement. This could lead to a double taxation of the income earned by the partner through the partnership during the year of immigration to Canada. Conversely, when an individual ceases to reside in Canada, under subsection 128.1(4) the individual will be deemed to have disposed, at the time he ceases to reside in Canada, of each (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1480 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE property owned by him, other than property that is taxable Canadian property. Note that a partnership that has, at any time during the 12 months immediately preceding its disposition, a fair market value in excess of 50 percent of its assets by way of a Canadian resource property or any other property used in carrying on a business in Canada will be deemed to be taxable Canadian property. Therefore, the emigrating Canadian taxpayer who holds an interest in a partnership that does not qualify as taxable Canadian property will be deemed to have disposed of that capital property upon his ceasing to reside in Canada. It should be noted that drawings at any time during the year reduce the partnership’s ACB. Earnings accruing throughout the year do not enter into the reckoning of the partnership’s ACB, but they do enter into the reckoning of the fair market value of that partnership interest at the time of departure. The departing resident will therefore be deemed to have disposed again and be subject to a capital gain on the income that accrues in the partnership prior to the emigration. This second element of inequity may be offset by adjustments to the cost base of the non-Canadian partnership interest suffered by the party when he first immigrated to Canada. In short, immigrants and emigrants who are partners in partnerships, particularly foreign partnerships, may be subject to an element of double taxation. Pushing Down Basis in a Partnership to the Underlying Assets of the Partnership An individual who purchases an interest in a partnership may have an ACB in that partnership that is far in excess of his pro rata share of the net cost amount of the net assets underlying the partnership interest. Is there any way in which the taxpayer can cause his outside cost base to become his cost base inside the partnership in the assets of the partnership? In Canada, this result can be achieved only with the greatest of difficulty. The partnership must first be wound up under subsection 98(3). The partner must then apply his excess cost base to bump up any non-depreciable capital property; then all the partners must reconstitute the partnership by transferring their assets back into the partnership. This arrangement is extremely cumbersome, and the subsection 98(3) windup may in fact be a taxable event to other members of the partnership. As a result, a partner will seldom be able to push down his cost base to the underlying assets of the partnership, even the non-depreciable capital assets of the partnership. There should be a simple election by which a taxpayer can, in certain circumstances, transfer his excess outside ACB to his net pro rata share of the cost amount of the partnership assets. Obviously, this election would be made only with respect to non-depreciable capital property. This very analysis may also lead to the observation that a partner who is going to sell his partnership interest in a taxable transaction may wish to rearrange his affairs so that the prospective incoming partner purchases goodwill from the partnership and then transfers that goodwill back into the partnership as his capital contribution, while the outgoing partner accepts a complete allocation of the gain on the sale of goodwill as a taxable event allocable only to the departing partner. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1481 Partnership Interests Remain Non-Qualified Investments for Tax-Deferred Plans It should be noted that the definition of “foreign property” in paragraph 206(1)(i) for the purposes of the deferred income plans indicates that a partnership interest includes all partnership interests (unless prescribed). This is so notwithstanding that every one of the assets within the partnership itself might otherwise be a qualifying investment if held outside the partnership. This interpretation seems especially harsh, and prevents the tax-deferred plans from making qualifying investments in Canadian partnerships that hold only Canadian real property. Butterflying Assets from a Partnership Beginning in the late 1970s, section 55 was expanded to include, indirectly, the divisive reorganization known as a butterfly. Throughout the 1980s, the butterfly was expanded by legislative changes and the continuing stream of administrative interpretations from Revenue Canada. In February 1994, the butterfly provisions were significantly overhauled and rendered far more difficult to comply with. Notwithstanding the narrowing of the provisions, Revenue Canada’s reluctance to allow assets to be butterflied from a partnership is decidedly puzzling. It has been suggested that the butterfly provisions for partnerships could immediately be added if Revenue Canada would merely agree that subsections 85(2) and 85(3) could be read in such a way that the transferee corporation referred to therein was not one transferee corporation but more than one. If “transferee corporation” was construed in the plural, there would arise a complete opportunity to use the two subsections to achieve a butterfly of assets from a partnership using two or more corporations. In the mid-1970s, Revenue Canada was prepared to say that “transfer corporation” could in fact be read in the plural. Sometime around 1975, however, these informal interpretations were withdrawn and Revenue Canada indicated that henceforth it was prepared to interpret the phrase only in the singular. As a result, the opportunity to butterfly assets from a partnership seems to be completely absent. Subsection 93(3) is not useful in butterflying assets from a partnership because of its provision that each and every partner must receive a pro rata undivided interest in each and every asset of the partnership. Clearly, the time is long overdue for Revenue Canada to extend the butterfly reorganization to partnerships as well as to corporations. Bumping Property Other Than Non-Depreciable Capital Property: The Little Egypt Bump On December 4, 1985, the Income Tax Act was amended in such a way that the bump applicable on the windup of a partnership (subsections 98(3) and 98(5)) would most closely resemble the bump on the windup of a subsidiary (subsection 88(1)). Under the old rule, it was possible on the windup of a partnership to bump every kind of partnership property. Under the new rule, the bump was restricted in its application to nondepreciable capital property. However, it is important to remember that while the old bump (the “Little Egypt” bump) is significantly precluded (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1482 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE from future use, it is nevertheless still available and may apply after December 4, 1985, when three conditions are met: 1) the member acquired the partnership interest before the relevant date (or after the relevant date in a non-arm’s-length transfer); 2) the assets being bumped were owned by the partnership before the relevant date; and 3) the partner is not a corporate partner that has undergone a change of control since the relevant date. Further, a portion of the same partner’s partnership interest may qualify for the old bump, and another portion may qualify only for the new bump. It is time that the old bump was given the continuing dignity that it deserves: it should be properly incorporated into the Act as a separate subparagraph or paragraph where it can be clearly read and understood. It should not, as it now is, be relegated to fine print by way of notes to subsection 98(3). This is an unreasonable attempt to bury the legitimate and ongoing application of the old “Little Egypt” bump. Subsection 96(1.1): Ongoing Problems and Deficiencies As previously discussed, subsection 96(1.1) represented a codification of administrative interpretations. Though useful, it leaves unanswered a number of questions. Why, for example, is subsection 96(1.1) restricted to those partnerships whose principal activity is the carrying on of business in Canada? Why the “in-Canada” requirement to give the commonsense results of subsection 96(1.1)? What interpretation is applied when the partnership is in fact carrying on business principally outside Canada? The income that is earned by the former partner from the partnership pursuant to subsection 96(1.1) has many of the attributes of active business income. Even though it may be paid periodically, it will be taxable to the recipient only at the year-end of the partnership. Furthermore, if paid to a non-resident, it will constitute under subsection 96(1.6) income earned by the non-resident from carrying on business in Canada. Why, then, is this income not “earned income” that qualifies in determining whether the recipient is entitled to make RRSP contributions with respect to this kind of income? Further, this kind of income is income that arises quite naturally when one of the partners withdraws from a two-person partnership and the remaining partner continues to allocate income to the departing partner. Revenue Canada has indicated that it will not interpret subsection 96(1.1) to allow the allocation of income from a (present) proprietorship to a former partner. Is it possible for the proprietorship to deduct such allocated amounts in reckoning the proprietorship income pursuant to paragraph 12(1)(g)? Clearly, such received amounts would be taxable in the hands of the recipient. There should be a provision for a former partnership that is now a proprietorship to make such allocations, whereby both the payer and the payee agree that such amounts are ordinary income and ordinary deductions rather than capital payments. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1483 Problems with the Operation of Subsection 98(5) Subsection 98(5) deals with the circumstances in which a partnership business converges and is carried on as a proprietorship. While the subsection is easily read, there are a number of problems in its continuing interpretation. 1) Consider, for example, the case in which company A and company B are each partners in the AB partnership. Company A and company B decide that they are going to amalgamate to form company AB . As a result of their amalgamation, the two partners have converged into one ongoing ownership of the economic enterprise, namely, company AB. Intuitively, one knows that subsection 98(5) should apply; technically, however, the amalgamated corporation (deemed to be a new company for income tax purposes) was a not a partner immediately before the partnership converged to form the proprietorship. 2) When all the partners simultaneously sell their partnership interests to a willing buyer who was not a partner at the time of the sale, subsection 98(5) seems not to apply. Obviously, the problem can be avoided to the extent that the buyer can, immediately prior to purchase, become a partner in the partnership. Further, it is unclear what results do follow if subsection 98(5) does not apply in the circumstances. 3) In the classic case in which partner A and partner B are carrying on the AB partnership and partner A buys out partner B, in the absence of any express agreement at the time of the purchase, which of them is liable to pay tax on the stub period earnings of the partnership up to the time that partner B sold his partnership interest? Is the stub period income taxable in the hands of partner B because he was a partner for part of the year? Or is the stub period income taxable to partner A because he has bought out the old partnership interest and carries on the partnership business? 4) In many two-person partnerships, the deceased partner will be unable to transfer a continuing partnership interest to a beneficiary, either because of a partnership agreement that triggers a sale to the surviving partner (which will preclude the indefeasible vesting of the partnership interest in the beneficiary) or because of rules of professional partnerships that prevent the non-professional beneficiary from being a partner in a partnership carrying on a professional practice such as medicine, law, or accounting. Subsection 98(5) appears to prevent the ongoing partner from agreeing to purchase a package of assets from the beneficiaries instead of purchasing a capital interest as anticipated in subsection 98(5). 5) Subsection 98(5) is not elective and applies automatically. Why does it apply only in respect of a Canadian partnership? What are the results in a similar fact pattern involving a non-Canadian partnership? 6) A problem may arise in the interaction of subsections 98(5) and 98(3). Consider the following. Two corporate partners carried on a business in partnership. After a number of years of partnership, it was decided that one partner would buy out the other. The intention was to dissolve (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 1484 CANADIAN TAX JOURNAL / REVUE FISCALE CANADIENNE the partnership and distribute an undivided interest in each asset to each of the partners (subsection 98(3)), and then to have the continuing partner purchase the retiring partner’s interest in all the assets. It was hoped that this would give the continuing partner a rollover as to one-half of the assets, while the disposing partner would be taxed on the gains on the assets that were sold. The problem arose in the interaction of subsections 98(5) and 98(3). Subsection 98(5) seems to say that if one of the partners is going to continue the business, then the other partner will be denied any form of rollover treatment and a gain will be realized at the partnership level. Subsection 98(4) provides that subsection 98(3) is not applicable in any case in which subsection 98(5) is applicable. This seems to produce an unreasonable conflict in certain circumstances. In summary, the rules of subsection 98(3), which might be beneficial to all partners, are not available if one of the partners, within the three-month period after the termination of the partnership, carries on the business formerly carried on by the partnership and uses therein some of the partnership property received by him in exchange for his partnership interest, so that subsection 98(5) becomes applicable. This rule seems particularly unfair when the partners, as part of the process of negotiating the dissolution of the partnership, might have agreed that each would take an undivided interest in each property and that subsection 98(3) should apply. If one of the partners should subsequently commence to carry on the business formerly carried on by the partnership (which may be a common occurrence), then subsection 98(3) will not apply even though an election under the subsection has been jointly made by all the parties. The partner who breaches the agreement will be protected by the rules in subsection 98(5). More Confusion About the Transparent Nature of a Partnership: The Robinson Trust Case A recent decision of the Tax Court of Canada has cast some doubt on the principle of transparency for partnerships in Canada. In Robinson Trust et al. v. The Queen,8 the taxpayer trust was a limited partner of a partnership that carried on an active business. The taxpayer trust wanted to apply the exemption under subsection 122(2) of the Act so that not all of its income would be subject to the top marginal rate of tax. For the exemption to apply, the trust could not be carrying on an active business. Under the normal transparency principle, because the partnership is carrying on an active business the trust is also carrying on an active business and is therefore unable to claim the exemption. The court, however, held that the exemption applied. In particular, the court said that the trust’s interest in the limited partnership did not cause it to carry on an active business because the trust never exercised a management role in the partnership and accordingly did not take part in the business of the partnership. Nonetheless, Revenue Canada has confirmed that notwithstanding the Robinson 8 93 DTC 1179 (TCC). (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5 A QUARTER CENTURY IN PARTNERSHIPS 1485 Trust case, partnership assets used in an active business are considered to be used by the partners in an active business. When a Deceased Partner’s Capital Account Is in Deficit When a deceased partner’s estate or heirs who do not acquire a partnership interest are required to make a payment to the partnership of which the deceased was a member in an amount which, if it had been paid by the partner while alive, would have increased the ACB of the partnership interest pursuant to subparagraph 53(1)(e)(iv), the department allows the ACB of the deceased partner’s partnership interest immediately prior to the death to be increased by the amount so paid. This administrative relief is found in Interpretation Bulletin IT-278 R2. 9 This concept warrants legislative clarification. Life Insurance Proceeds Received by a Partnership and Paid Out to a Deceased Partner: A Possible Problem Revenue Canada was asked to consider the treatment of life insurance received by a partnership upon the death of one of the partners and to address the issue of the treatment for tax purposes of the partners, including the deceased partner. Subparagraph 53(1)(e)(iii) of the Act provides for an increase in the ACB of a partnership interest by the taxpayer’s share of life insurance proceeds (net of the ACB of the policy). The question is whether and to what extent the net insurance proceeds increase the ACB of the partnership if they arise when the net life insurance proceeds are allocable solely to the deceased partner and are used to pay the estate of the deceased for the partnership interest. It is Revenue Canada’s position that the subparagraph will apply only to the surviving partners because the subparagraph refers to the taxpayer’s share of any proceeds of a life insurance policy received by a partnership in consequence of the death of any person insured under the policy. Because the adjustment can only take place after the proceeds are received by the partnership, and because the deceased partner is deemed to have disposed of the interest immediately before death and is no longer a partner at the time the proceeds are received, no adjustment is possible with respect to the deceased’s former interest in the partnership. Although the proceeds received by the partnership may be earmarked for use by the partnership to fund a payment to the deceased’s estate, the estate does not have a right to any direct share in the actual life insurance proceeds. While I look forward to the changes that will come in the next 25 years to the partnership provisions of the Income Tax Act, I doubt that I will be called upon in 2020 to review those changes. Alas, perhaps the changes will no longer be relevant to me! 9 Interpretation Bulletin IT-278R2, “Death of a Partner or of a Retired Partner,” September 16, 1994. (1995), Vol. 43, No. 5 / no 5