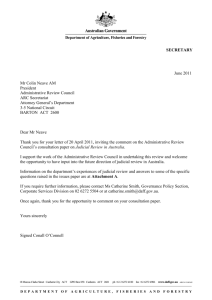

discussion paper reform of judicial review in nsw

advertisement