File - Military Tactics

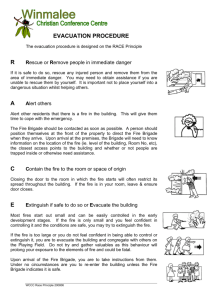

advertisement