The Ties that Bind: Ted Rogers, Larry Tanenbaum, and the Toronto

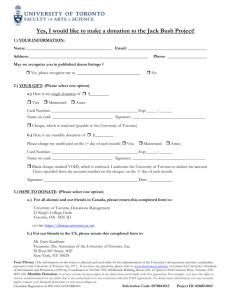

advertisement