Culture, Change and Community Justice

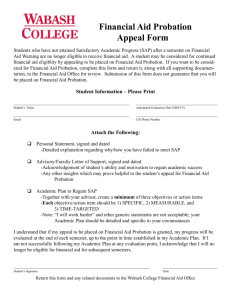

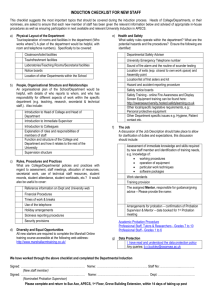

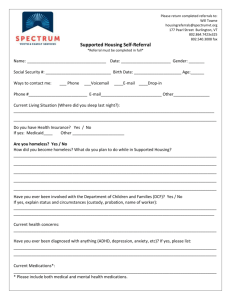

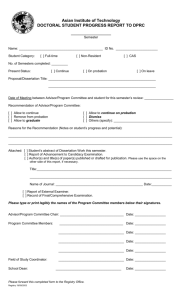

advertisement