An Institution-Based View of the Competitive Advantage of Firms in

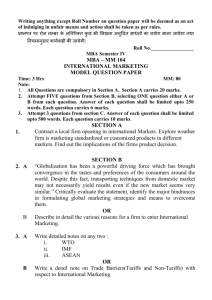

advertisement