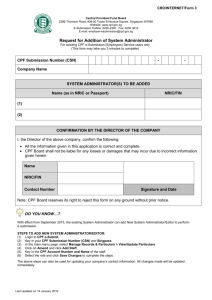

Central Provident Fund in Singapore

advertisement