Chapter Five Analysis of Three Sub

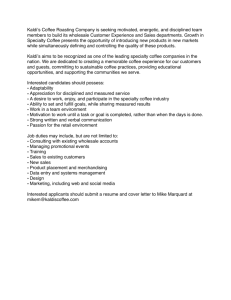

advertisement