Key Factors for Successful Evaluation and Screening of Strategic

advertisement

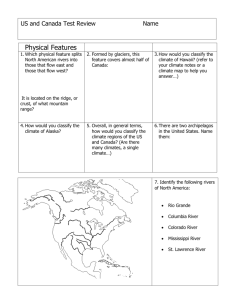

Asia Pacific Management Review (2007) 12(3), 151-160 Key Factors for Successful Evaluation and Screening of Strategic Alliance: A Case Study in the Telecommunications Industry Ming-Kuen Wang and Kevin P. Hwang* Department of Transportation and Communication Management Science, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, R.O.C. Accepted in June 2007 Available online Abstract This research uses the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to analyze key factors in evaluating and screening strategic alliance partners in the telecommunications industry. Telecommunications companies can utilize key factors of strategic alliances to provide self-growth and obtain competitive advantage opportunities for expanding global market share. This research summarizes the evaluation and screening criteria of strategic alliance partners via a questionnaire of 30 Chunghwa Telecom executives who had actually participated in alliance decisions or related tasks and who had employed AHP screening criteria. Findings include three key factors in evaluating and screening partners: complementation of marketing channels and skills, past cooperation experience of both parties, and complementation of technology and resources. This research can provide a reference to telecommunication companies when evaluating and screening partners. Keywords: Strategic alliance; Analytical hierarchy process; Partner evaluation and screening; Key factor 1. Introduction communications companies will inevitably make strate- gic plans, adopt strategic alliances, and expand to a global telecom market aggressively to increase competitiveness and profitability. The Taiwan telecommunications market has been liberalized for over ten years. Market dynamics have resulted in three dominant companies: Chunghwa Telecom, Taiwan mobile, and Far Eastone, with each holding about one third market share. The opening of 3G and the implementation of Mobile Number Portability (MNP) will introduce increased competition. Because of fierce competition, limited resources, technical barriers, capital shortages, and geographical limitations, it is difficult for a company to operate independently and to profit in the global market. Therefore, many companies have started to seek alliances with other companies or create cooperation opportunities with other partners in response to global competition. Such cooperations promise to reduce operating risks, to help obtain technical knowledge and resource complements--increasing the competitiveness of the company. Wu (1996) offers that the basic purpose of strategic alliances is to either strengthen a businesses’ self competitive advantage or to seek competitive balance. Strategic alliances utilize synergistic effects to make every partner able to take advantage of complementary combinations, which can result in greater strength. However, strategic alliances also present risks. Liu (2000) shows that management complexity is increased. Therefore, the company must consider the traits of alliance targets (products, technologies, etc.) and decide how many companies should participate; they must also decide the target for the participating alliance. Designing and managing a bad alliance group will make management difficult and cause conflicts; this will result in the disappearance of the potential value obtained by the alliance relationship. Because Chunghwa Telecom is the leader of the Taiwan telecommunications industry, this research uses Chunghwa Telecom as a example to study, compare, analyze, and summarize the choices of strategic alliances that Taiwan telecommunications companies face. It faces these conditions in an external environment of growing 3G and MNP policy after market liberalization and internal environment change, due to the company's privatization. Further, this research explores the key Varis et al., (2005) 1 show that an international growth strategy has become the biggest challenge a company faces when international expansion offers a company growth and added value. The telecommunications industry not only has the high technology and enormous capital, but it also is a service industry. Since such a multi-characteristic industry faces a competitive environment with various changes, global tele* Email:wmk2582@cht.com.tw 151 Ming-Kuen Wang et al.,/Asia Pacific Management Review (2007), 12(3), 151-160 ing skills, and experience are important. This research proposes that complementary skills should be summarized as: alliance networks, technology resources, marketing channels, financial resources; the partner’s previous experiences are used as the sub-criterion level (Geringer, 1991; Stafford, 1994; Brouthers et al., 1995; Dacin et al., 1997; Tam & Tummala, 2001; Nielson, 2003; Holtbrugge, 2004). factors valued by telecommunications companies when choosing strategic alliance partners. 2. Definition of Strategic Alliance Aaker (1992) contends that the strategic alliance is a long-term cooperation relationship between two or more companies; and it combines an advantageous leverage to achieve strategic goals. It is one kind of tactic; it also includes the cooperation of mutually needed resources and technologies; furthermore, it generates strategic value. Wu (1996) believes that the strategic alliance is the non-market oriented company deals between competitors to participate in activities of existing potential competitors via technology transfer to each other, consignment sale contract, minority or equal shares investment (i.e., joint venture company), capacity swap, joint marketing, cooperative research and development, cooperative production, or a combination of each of the above activities. Therefore, exchanges, product co-sharing or co-development, and autonomic affiliations of technology and services between companies also belong to strategic alliances (Gulaty, 1998). Spekman et al., (1998) considers the strategic alliance as the close, long-term, and mutual beneficial agreement relationship between two or more partners; in the agreement, resources, knowledge and skills are shared in order to strengthen each partner’s position. A strategic alliance occurs when two or more organizations agree to use each other’s resource to achieve the strategic goals that one single company would not be able to reach (Ahwireng-Obeng, 2001). (2) Cooperative culture between partners The primary key of creating cooperative culture lies in symmetry. When the size difference between alliance partners is small or financial resources and the internal work environment are compatible, the strategic alliance will tend to succeed. Symmetry should exist in each other’s top management team; namely, top management teams between partners should establish peer relationships. Brouther et al., (1995) argue that organizational culture, trust, commitment, and past cooperative experiences are important; while Chen (2002) proposes to add cooperative vision to constitute the fourth sub-criteria for constructing cooperative culture. (3) Compatible goals of cooperative partners A clear goal is indispensable to successful strategic alliances. In order to avoid vague and different goals, achievement levels of original goals also must be regularly reviewed. Brouther et al. (1995) and Gonzalez (2001) contend that strategic goals need to be compatible; this research adopts the view that the compatibility of the management team is also an important factor in a successful strategic alliance, as Stadfford (1994), Lin & Chen (2004), propose. Liu (1996) states that the compatibility of operational policy between organizations must be stressed in order to have compatible strategic alliance goals. This research defines the strategic alliance as two or more companies, for the purpose of sharing each other’s market, technologies, resources, knowledge and skills, sign a long-term mutual benefit agreement and operate independently and freely to strengthen the competitive abilities of alliance members. (4) Commensurate risks sharing At the beginning of a strategic alliance, risks distribution issue must be prudently considered. This research summarizes previous scholars’ viewpoints: Liu (1996) thinks that reputation and renown of alliance partners may influence the reputation and performance of the whole alliance. Brouther et al. (1995) consid that competition and conflict of interests in the industryand the financial risk of extra cost incurred by the alliance are the risks that a strategic alliance possibly faces. Wu (1996) contends that the risk of communication barriers may occur during correspondence when a company is investing in or seeking cooperation. Lambe and Spekman (1997) hold that innovation of technology will cause highly uncertain risk in the industry. Therefore, they suggest that companies should apply the strategic alliance method to reduce this risk. We have gathered domestic and international literature about the evaluation of strategic alliance partners and explored the conceptual criteria in relation to Taiwan telecom companies, who are evaluating and screening strategic alliance partners. For the main criteria, we have adopted four main criteria of selecting strategic alliance partners, proposed by Brouthers et al. (1995). Combining all other scholars’ research, we summarize the criteria structures, considered by strategic alliance decision makers of telecom industry, as follows: (1) Complementary skills offered by the partner Brouthers et al., (1995) holds that the most basic overview of a partner includes the aspects of technology and market; it also should consider the experience of the partner and the realistic contributions; they also contend that the partner’s financial resources, market- 152 Ming-Kuen Wang et al.,/Asia Pacific Management Review (2007), 12(3), 151-160 second stage questionnaire. The second stage questionnaire is mainly based on results of the first stage to build hierarchical structure; and it deploys pair-wise comparisons, conforming to the application of rating scales. This research uses Chunghwa Telecom as the research subject and surveys executives who are actually responsible for alliance tasks in the three branches of the company: Mobile Business, Data Communications, and International Business. A total of 45 questionnaires were sent out, starting on March 27, 2006. The response deadline was May 3, 2006; 30 responses were valid, with a response rate of 67%. 3. Methodology 3.1 Structure Because each evaluation criterion obtained by this research is a qualitative, it is difficult to quantify for practical application. Therefore, this research deploys two-stages of expert questionnaires to find out the criteria of evaluating and screening strategic alliance partners, which Chunghwa Telecom uses. In the first stage, we use a fuzzy Dephi method to screen relevant influence factors and utilize the concept of threshold value to select proper evaluation criteria. In the second stage, we utilize evaluation criteria obtained from screening, fitting Analytic Hierarchy Process, to get the relative weight of evaluation criteria. The hierarchical structure is shown in Figure 1. 3.3 Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Due to rapid environmental changes, aspects of consideration by decision makers have become more complicated and varied. In order to solve this problem, Saaty (1980) proposes the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). AHP can offer decision makers sufficient information about selecting the appropriate scheme. The more weighted value the scheme has, the higher priority for scheme adoption. AHP can be used to reduce the risks of making wrong decisions and helping decision makers to make sound judgments (Deng & Tseng, 1989). 3.2 Questionnaire Design and Analysis Questionnaire analysis mainly consists of a fuzzy Dephi method and an Analytic Hierarchy Process in two stages. The first stage questionnaire inquires of expert opinion. Items result from summarizing geometric means of above mentioned items of literature review, and items that reach the threshold value from each dimension are used as the base of developing Figure 1. Research Structure 153 Ming-Kuen Wang et al.,/Asia Pacific Management Review (2007), 12(3), 151-160 AHP retrieves majority opinions of experts and deploys pair-wise comparisons to find the relative importance of decision elements; it further selects the biggest relative weighted scheme as the best scheme by linking hierarchy levels. After summarizing opinions of evaluators, we evaluate items via a nominal scale to give proper comparison values. In general, a geometric mean is used to serve as a basis for forming the comparison matrix. (5) Establishment of a pair-wise comparison matrix 3.4 Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) Procedure While conducting pair-wise comparison among elements for n elements, n (n-1)/2 comparisons are needed. Next, we put the measure of n elements comparison results in the upper triangular part of the comparison matrix, while the bottom triangular part serves as the reverse value of the upper triangular part’s relative value. Then, we can obtain a pair-wise comparison matrix A as shown in Equation (1): a12 L a1n ⎤ ⎡ 1 ⎢1 a 1 L a 2 n ⎥⎥ (1) A = ⎢ 12 ⎢ M M O M ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ ⎣1 a1n 1 a 2 n L 1 ⎦ The AHP procedure can be divided into the following steps: (1) Definition of decision problems While using AHP, for evaluating the hierarchy of key factors, the direction of the problem must be fully grasped. First of all, the problem must be clarified, and the scope of the problem must be defined clearly. (2) List of every evaluating factor When listing every evaluating factor, relevant literature, group brainstorming, and Delphi methods are used to assemble opinions of scholars and experts. Their professional knowledge and practical experience are used to list every evaluating factor. Where aij denotes the relative importance of element i as compared with element j (3) Development of hierarchy structure (6) Finding eigen vector and maximized eigenvalue Every evaluating factor is compartmentalized to a hierarchy layer, according to the relevant relationship of each factor and independent level. Saaty (1980) suggested that each layer has no more than seven items so as to avoid conflicts that affect evaluating results. Saaty and Vargas (1982) propose four approximate eigen vector solution characteristics. This research adopts the row vector geometric mean standard method, as shown in Equation (2); this is also called normalization of the geometric mean of the rows (NGM) method; this method is often used and also has the best accuracy. (4) Pair-wise comparison and evaluation Pair-wise comparison is conducted according to the relative importance of each evaluating factor. This can lighten the decision makers’ burden of thinking; it can even more clearly present the relative importance of decision factors. AHP employs a nominal scale as the evaluating indicator of pair-wise comparisons, which can be divided into nine scales as shown in Table 1: n n Wi = Definition 1 Equal Importance 3 Weak Importance 5 Essential Importance 7 Very Strong Importance 9 2, 4, 6, 8 Absolute Importance Intermediate Values of Neighborhood Scales ij i,j=1,2,…,n j =1 (2) n n ∑ ∏a n i =1 ij j =1 Next, we further calculate the maximized eigen value λ max . First, we multiply pair-wise the comparison matrix A by eigen vector Wi to get a new vector Wi ' , as shown in Equation (3), where each vector value of Wi ' is divided by each vector value that corresponds to the original vector Wi . Then, use all obtained values to calculate an arithmetic average, deriving λ max , as shown in Equation (4). Table 1. Meanings and Explanation of AHP Scale Evaluating Scale ∏a Explanation Contributions of two criteria are equally important Experience and judgment moderately favor one scheme over another Experience and judgment strongly favor one scheme over another In practice, a scheme is favored very strongly over another Experience and judgment favor one scheme over another When compromise judgment values are needed a12 ⎡ 1 ⎢1 a 1 Wi ' = A × Wi = ⎢ 12 ⎢ M M ⎢ ⎣1 a1n 1 a2n 1⎛ n W' ⎞ λmax = ⎜⎜ ∑ i ⎟⎟ n W ⎝ i =1 i ⎠ (7) Consistency test (A) Consistency index Source: Saaty (1980) 154 L a1n ⎤ ⎡W1 ⎤ ⎡W '1 ⎤ L a2n ⎥⎥ ⎢⎢W2 ⎥⎥ ⎢⎢W ' 2 ⎥⎥ (3) × = O M ⎥ ⎢M ⎥ ⎢ M ⎥ ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ L 1 ⎦ ⎣Wn ⎦ ⎣W ' n ⎦ (4) Ming-Kuen Wang et al.,/Asia Pacific Management Review (2007), 12(3), 151-160 C .I . = λmax − n where n j denotes the number of elements contained in j level, Wij is the comprehensive weight value of i element in j level; U i , j +1 means the consistency index of j+1 level toward the i element in j level; and Ri , j +1 is the random index of j+1 level toward the i element in j level. If CRH≦0.1, the overall hierarchy of the developed comparison evaluation has consistency. (5) n −1 The smaller C.I. the value is, the higher the consistency is-- while C.I.=0 means total consistency. Generally speaking, C.I.≦0.1 denotes acceptable evaluating values within the matrix. If C.I.>0.1, we re-calculate the pair-wise comparison matrix until the C.I. value improves to an acceptable level. (B) Consistency ratio C.R. = C.I . R.I . (9) Calculating total priority vector of the overall hierarchy After the consistency of the overall hierarchy reaches an acceptable level, the last AHP step is to combine the relative weights of the elements of each level to obtain each decision scheme that corresponds to the relative priority order of the decision goal. (6) When C.R.≦0.1, the results of data judgment have consistency. If C.R. >0.1, we re-calculate the matrix until C.R. the value improves to an acceptable level. The random index (R.I.) is as shown in Table 2: 4. Results and Discussions 4.1 Strategic Alliance Main Criterion Table 2. Random Index n R.I. 1 0 2 0 3 0.58 4 0.9 5 1.12 6 1.24 Table 3 shows each pair-wise comparison matrix and the weight for the strategic alliance main criterion: 7 1.32 From Table 3 results, C.I. and C.R. values are all smaller than 0.1, showing this pair-wise comparison matrix has consistency; namely, every interviewee shows consistency toward the evaluation of this dimension. The importance sequencing is as follows: complementary skills > risks and risks sharing > cooperative culture > compatible goals. Therefore, the results show strategic alliances emphasize complementary skills. Source: Saaty (1980) (8) Finding the overall consistency ratio hierarchy (CRH) First, calculate the overall consistency ratio hierarchy (CIH) and overall random index hierarchy (RIH), the algorithms for which are as shown in Equation (7) ~ Equation (9): h nj CIH = ∑∑ WijU i , j +1 (7) 4.2 Complementary Skills j =1 i =1 h Results of Table 4 show C.I. and C.R. values are both smaller than 0.1, meaning this comparison matrix has consistency; that is, every interviewee shows consistency toward comparisons of complementary skills. The importance sequence is as follows: marketing channel and skills complementation > technology and resource complementation > alliance network complementation. nj RIH = ∑∑ Wij Ri , j +1 (8) CIH RIH (9) j =1 i =1 CRH = Table 3. Pairwise Comparison Matrix of Main Criterion Main Criterion Complementary Skills Compatible Goals Cooperative Culture Risks and Risks Sharing Weight of Each Dimension Complementary Skills 1.00000 2.33030 1.63143 1.03186 (1)0.34391 Compatible Goals 0.42913 1.00000 1.12260 0.96068 (4)0.20155 Cooperative Culture 0.61296 0.89079 1.00000 1.05524 (3)0.21290 Risks and Risks Sharing 0.96912 1.04093 0.94765 1.00000 (2)0.24163 λmax = 4.07101, C.I.= 0.02367, C.R.= 0.02630 155 Ming-Kuen Wang et al.,/Asia Pacific Management Review (2007), 12(3), 151-160 Table 4. Pair-wise Comparison Matrix of Complementary Skills Technology and ReMarketing Channel and Weight of source ComplementaSkills Complementation Each Item tion Alliance Network Complementation Complementary Skills Alliance Network Complementation Technology and Resource Complementation Marketing Channel and Skills Complementation Relative Weight 1.00000 0.84795 0.46073 0.23137 (4)0.07957 1.17931 1.00000 0.59365 0.28104 (3)0.09665 2.17048 1.68450 1.00000 0.48759 (1)0.16769 λmax =3.00087,C.I.= 0.00044,C.R.= 0.00075 Table 5. Pairwise Comparison Matrix of Compatible Goals Compatible Goals Compatibility of Operational Policies Compatibility of Management Teams Compatibility of Strategic Goals Weight of Each Item Relative Weight 1.00000 1.18942 0.86716 0.33675 (7)0.06787 0.84075 1.00000 1.11806 0.32649 (9)0.06581 1.15319 0.89441 1.00000 0.33675 (8)0.06787 Compatibility of Operational Policies Compatibility of Management Teams Compatibility of Strategic Goals λmax =3.02035,C.I.=0.01017,C.R.=0.01754 exhibits consistency toward comparisons of cooperative culture. Its importance sequencing is as follows: both parties’ past cooperation experience > trust and commitment > cooperative visions. 4.3 Comaptible Goals From the results of Table 5, we know that both C.I. and C.R. values are smaller than 0.1-- showing that this pair-wise comparison matrix has consistency; this means every interviewee exhibits consistency toward comparisons of compatible goals. Its importance sequencing is as follows: compatibility of operational policies=compatibility of strategic goals > compatibility of management teams. 4.5 Risks and Risks Sharing From the results of Table 7, we know both C.I. and C.R. values are smaller than 0.1, showing this pair-wise comparison matrix has consistency; that is, every interviewee has consistency toward comparisons of risks and risks sharing. Its importance sequencing is: competitiveness or conflict of interests in the industry > past reputation and renown > risk sharing of task environment uncertainty > potential communication barrier. 4.4 Cooperative Culture In the results of Table 6, both C.I. and C.R. values are smaller than 0.1, showing this pair-wise comparison matrix has consistency, namely; every interviewee Table 6. Pair-wise Comparison Matrix of Cooperative Culture Cooperative Culture Both Parties’ Past Cooperation Experi- Cooperative Visions ence Trust and Commitment Weight of Each Item Relative Weight Both Parties’ Past Cooperation Experience 1.00000 3.59124 2.08514 0.56422 (2)0.12012 Cooperative Visions 0.27846 1.00000 0.47979 0.14743 (13)0.03139 Trust and Commitment 0.47958 2.08424 1.00000 0.28835 (10)0.06139 λmax = 3.00404, C.I. = 0.00202, C.R. = 0.00349 156 Ming-Kuen Wang et al.,/Asia Pacific Management Review (2007), 12(3), 151-160 Table 7. Pair-wise Comparison Matrix of Risks and Risks Sharing Risks and Risks Sharing Past Reputation and Renown Competitiveness or Conflict of Interests in the Industry Potential Communication Barrier Risk Sharing of Task Environment Uncertainty Past Reputation and Renown Competitiveness or Conflict of Interests in the Industry Potential Communication Barrier Risk Sharing of Task Environment Uncertainty Weight of Each Item Relative Weight 1.00000 1.17430 1.38397 1.19476 0.29042 (6)0.07017 0.85157 1.00000 2.07582 1.20578 0.29726 (5)0.07183 0.72256 0.48174 1.00000 1.20578 0.19802 (12)0.04785 0.83699 0.82934 0.82934 1.00000 0.21430 (11)0.05178 λmax = 4.06252, C.I. = 0.02084, C.R. = 0.02316 reasons for undertaking strategic alliances. Accordingly, companies often combine each other’s complementary technologies and resources via strategic alliances to increase competitive advantages of companies (Tsang, 1998; Hitt & Dacin, 2000; Schilling, 2005). A strategic alliance is created when companies cooperate because of mutual needs and risks sharing to achieve common goals (Kogut, 1988). This verifies and supports the viewpoints of scholars. In addition, the first five key factors that are most stressed are: marketing channels and skills complementation; both parties’ past cooperation experience; technology and resource complementation; alliance network complementation; and competitiveness or conflict of interests in the industry. The least emphasized factors are cooperative visions; potential communication barriers; risk sharing of task environment uncertainty; trust and commitment; and compatibility of the management team. Chunghwa Telecom, the biggest telecommunications company in Taiwan, faces the saturation of market scale economy after privatization and is now aggressively turning to developing countries in the Asia-Pacific region to seek strategic alliances of trans-investments in the international market; it seeks to solicit strategic alliance partners who can co-invest to develop telecommunications markets in Asia-Pacific countries. Findings of this research can act as a reference for Taiwan telecommunications companies when seeking trans-investments strategic alliance partners. This is a solid contribution of this research to telecommunications industry. This study considers only the case of Chunghwa Telecom; furthermore, in order to improve the reliability of the survey, only executives and employees whom are familiar with partnering strategies are included in the survey; so, in terms of generality, there are some limitations. However, since most companies have adopted differing but similar policies, the results of the survey are still relevant to other telecommunications companies. Regarding the consistency of the whole level, relevant indices are as follows: CIH=0.031338 RIH=1.557322 CRH=0.020123 CRH is smaller than 0.1, showing this pair-wise comparison matrix has consistency; this implies that every interviewee has consistency toward the comparison of this item. 5. Conclusions Successful strategic alliances can help companies obtain competitive advantages in the market. Therefore, an organization’s important strategic issue is how to select the optimum alliance partner in the hope of minimizing input to achieve maximum output. Nevertheless, when a company makes a decision, it is quite common that changes of organizational environment and the complexity of decision factors are intermingled in the decision making process. Therefore, it is appropriate to form an evaluating project team within the organization to select the solving scheme. While choosing the strategic alliance partner, it is usual to face the problem of multiple criteria and many decision makers. Because this problem has the characteristics of unstructured openness, complex environmental factors need to be included when making decisions. Some criteria are often qualitative and are deeply influenced by accumulated experience and the subjective judgment of the decision makers, causing criteria weights to often be changed due to environmental variations at the time of decision making. We invited Chunghwa Telecom middle and higher level executives to conduct comparisons, and we employed AHP to understand the crucial factors of evaluating and screening strategic alliance partners in the telecommunications industry resulting in actual effects and meanings. Research results show complementary skills with partners, risks reduction, and risks sharing are the main 157 Ming-Kuen Wang et al.,/Asia Pacific Management Review (2007), 12(3), 151-160 References 159-179. Aaker, D.A. (1992). Developing Business Strategies, NY: John Liu, Chi-Mea. (2000). Global Business Appraisal on Alliance Strat- Wiley and Sons. egy, Economic review, 6(1), 114-126. Ahwireng-Obeng, F. (2001). Contribution to Successful Large-Small Liu, Yi-Ping. (1996). Study of Selationships among Strategic Alli- Business Linkaging in South Africa. International Council of ance Types, Goals,and Choosing Partner Standards: A Cause Small Business World Conference, Taipei, Taiwan. Study of Integrated Circuit Industry in Taiwan, Telecommuni- Brouthers, K.D., Brouthers, L.E. and Wilkinson, T.J. (1995). Strate- cation University Taiwan. gic Alliance: Choose Your Partners. Long Range Planning, Nielsen, B.B. (2003). An Empirical Investigation of the Drivers of 28(3), 18-25. International Strategic Alliance Formation. European Man- Cheng, E.B. (2002). A systematic Fuzzy MCDM Model for the agement Journal, 21(3), 301-322. Strategic Alliance Partners Selection of the Airlines is Pro- Saaty, T.L. (1980). The Analytic Hierarchy Process, NY: posed, Ocean University Taiwan. McGraw-Hill. Dacin, M.T., Hitt, M.A. and Levitas, E. (1997). Selection Partners Saaty, T.L. and Vargas, L.G. (1982). The Logic of Priorities, Boston: for Successful International Alliance, Examination of U.S. and Kluwer-Nijhoff. Korean Firms. Journal of World Business, 32(1), 3-16. Saaty, T.L. (1997). A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical Dun, Z.E. and Zun, K.S. (1989). Applied & Character of Hierarchy structures. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 15(2), Analysis Method(1), Journal of Statistic, 27(6), 5-22. 234-281. Tsang, E.W.K. (1998). Motives for Strategic Alliance: A Re- Schilling, M.A. (2005). Strategic Management Technological Inno- source-Based Perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Manage- vation, NY: McGraw-Hill. ment, 14(3), 207-221. Spekman, R.E., Forbes, T.M., Isabella, L.A. and MacAvor, T.C. Geringer, J.M. (1991). Strategic Determinants of Partner Selection (1998). Alliance Management: A View from the Past and a Criteria in International Joint Ventures. Journal of Interna- Look to the Future. Journal of Management Studies, 35(6), tional Business Studies, 22(1), 41-62. 747-772. Gonzalez, M. (2001). Strategic Alliances: The Right Way to Com- Stafford, E.R. (1994). Using Co-operation Strategies to Make Alli- pete in the 21th Century. Ivey Business Journal, 66(1), 47-51. ances Work. Long Range Planning, 27(3), 64-74. Gulati, R. (1998). Alliance and Networks. Strategic Management Tam, M.C.Y. and Tummala, V.M.R. (2001). An Application of the Journal, 19(4), 293-317. AHP in Vendor Selection of a Telecommunications system, Hitt, M.A. and Dacin, M.T. (2000). Partner Selection in Emerging Omega, 29(2), 171-182. and Developed Market Contexts Resource-Based and Organ- Varis, J., Kuivalainen, O. and Saarenketo, S. (2005). Partner Selec- izational Learning Perspectives. Academy of Management tion for International Marketing and Distribution in Corporate Journal, 43(3), 449-467. New Ventures. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, Holtbrugge, D. (2004). Management of International Strategic Busi- 3(1), 19-36. ness Cooperation: Situational Conditions, Performance Crite- Wu, C.S. (1996). International Business Management, Taipei: Zeu ria, and Success Factors. Thunderbird International Business Seng Ltd. Review, 46(3), 255-274. Kogut, B. (1988). Joint Ventures: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives. Strategic Management Journal, 9(4), 319-332. Lambe, C.J. and Spekman, R.E. (1997). Alliance, External Technology Acquisition, and Discontinuous Technological Change. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 14(2), 102-116. Lin, C.W.R. and Chen, H.Y.S. (2004). A Fuzzy Strategic Alliance Selection Framework for Supply Chain Partnering under Limited Evaluation Resources. Computers in Industry, 55(2), 158 Ming-Kuen Wang et al.,/Asia Pacific Management Review (2007), 12(3), 151-160 Appendix: Questionnaire Strategic Alliance Partners Factors 9:1 8:2 Importance of one factor over another 7:3 6:4 5:5 4:6 3:7 2:8 1:9 Complementary skills offered by the partner Complementary skills offered by the partner Complementary skills offered by the partner Cooperative culture between partners Cooperative culture between partners Compatible goals of cooperative partners Factors Cooperative culture between partners Compatible goals of cooperative partners Commensurate risks sharing Compatible goals of cooperative partners Commensurate risks sharing Commensurate risks sharing Complementary Skills Factors 9:1 8:2 Importance of one factor over another 7:3 6:4 5:5 4:6 3:7 2:8 1:9 Alliance Network Complementation Alliance Network Complementation Technology and Resource Complementation Factors Technology and Resource Complementation Marketing Channel and Skills Complementation Marketing Channel and Skills Complementation Compatible Goals Factors 9:1 8:2 Importance of one factor over another 7:3 6:4 5:5 4:6 3:7 2:8 Factors 1:9 Compatibility of Operational Policies Compatibility of Operational Policies Compatibility of Management Teams Compatibility of Management Teams Compatibility of Strategic Goals Compatibility of Strategic Goals Cooperative Culture Factors 9:1 8:2 Importance of one factor over another 7:3 6:4 5:5 4:6 3:7 Both Parties’ Past Cooperation Experience Both Parties’ Past Cooperation Experience Cooperative Visions 2:8 1:9 Factors Cooperative Visions Trust and Commitment Trust and Commitment 159 Ming-Kuen Wang et al.,/Asia Pacific Management Review (2007), 12(3), 151-160 Risks and Risks Sharing Factors 9:1 8:2 Importance of one factor over another 7:3 6:4 5:5 4:6 3:7 2:8 Factors 1:9 Competitiveness or Conflict of Interests in the Industry Potential Communication Barrier Risk Sharing of Task Environment Uncertainty Past Reputation and Renown Past Reputation and Renown Past Reputation and Renown Competitiveness or Conflict of Interests in the Industry Competitiveness or Conflict of Interests in the Industry Potential Communication Barrier Risk Sharing of Task Environment Uncertainty Risk Sharing of Task Environment Uncertainty Potential Communication Barrier Questionnaire sample scale respondents Corporation Mabile Telcos Data Telcos International Telcos President Director 1 1 3 2 Depart. Director 1 3 1 160 Supervisor Manager Forman Total 2 2 1 1 2 5 1 4 10 10 10