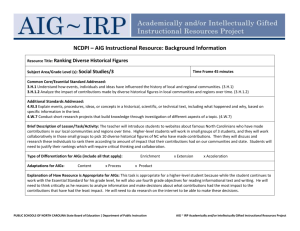

The AIG Bailout - Washington and Lee University School of Law

advertisement