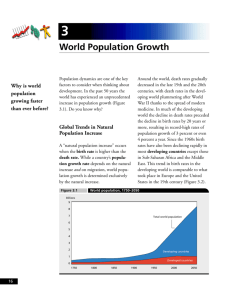

Global Demographic Divide - Population Reference Bureau

advertisement