514

Review

TRENDS in Genetics Vol.19 No.9 September 2003

Distribution of meiotic recombination

sites

Bernard de Massy

Institut de Génétique Humaine, 141 rue de la Cardonille, 34396 Montpellier cedex 5, France

Meiotic recombination generates gene conversion and

crossover events that are distributed heterogeneously

in the genome. Studies in yeast show that initiation of

recombination, which occurs by the formation of DNA

double-strand breaks, determines the distribution of

gene conversion and crossover events that take place in

nearby intervals. Recent data in humans and mice also

indicate the presence of highly localized initiation sites

that promote crossovers clustered around the region of

initiation and seem to share common features with

sites in yeast. On a larger scale, chromosomal domains

with various recombination rates have been identified

from yeast to mammals. This indicates a higher level of

regulation of recombination in the genome with potential consequences on genome structure.

During meiosis, recombination between homologous chromosomes generates gene conversion (nonreciprocal events)

and crossing over (reciprocal events). Analyses in many

organisms show that meiotic recombination events are not

distributed randomly in the genome. Given that homologous recombination can, in principle, spread over large

distances, the distribution of events depends on where

recombination is initiated as well as how far it extends.

The combination of genetic and molecular analysis in

Saccharomyces cerevisiae and, more recently, in mammals

shows that recombination events (gene conversion and

crossover) cluster tightly in the vicinity of initiation

sites. Therefore, the distribution of exchanges essentially

reflects the distribution of initiation sites. Here, I review

the properties of these sites and associated events in the

yeasts S. cerevisiae, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe,

mice and humans.

The current model for meiotic recombination

The current model of meiotic recombination combines

the double-strand-break repair (DSBR) model [1] and

the synthesis-dependent strand-annealing (SDSA) model

(Box 1) (reviewed in [2]). The combination of these pathways has been proposed to explain extra-chromosomal

recombination in mammalian cells [3] and human

minisatellite rearrangements [4]. Molecular analysis in

S. cerevisiae provides direct support for this model with

respect to meiotic recombination [5,6].

Several specific features of this model are particularly

relevant for the comparative analysis of events in yeast

and mammals presented below. First, the chromatid that

Corresponding author: Bernard de Massy (bdemassy@igh.cnrs.fr).

initiates and, therefore, where the DSB occurs, is the

recipient of genetic information. This leads to conversion

on the initiating chromatid. Conversion occurs by mismatch repair, and not by double-strand gap as originally

proposed. Second, the strand exchange is initiated and

extended from the 30 ends, thus, heteroduplex forms

initially in regions where degradation of 50 ends occurs

but can extend further by either strand displacement or

branch migration of Holliday junctions. Repair of heteroduplex produces either gene conversion or restoration

depending on the choice of the corrected strand. If Holliday

junctions are resolved within the interval defined by the

gene-conversion tract, the sites of crossing over map at

the boarders of these tracts. However, branch migration

of the Holliday junctions can lead to crossover away from

this region.

Local distribution of recombination in yeasts

DSBs, which are detected by molecular analysis, are

generated by Spo11 in conjunction with several other

proteins at many sites in the genome (reviewed in [7]).

Four levels of constraint have been observed with respect

to the distribution of DSBs in yeast: (1) at the nucleotide

level, DSBs are not distributed randomly, but no clear

sequence motif has been identified; (2) DSBs are commonly

located in accessible regions of the chromatin; (3) the

formation of DSBs appears to depend on chromosome

organization and to occur preferentially in chromatin loops

away from DNA-axis associations that are mediated by

cohesins and Red1 [8,9]; and (4) DSBs are clustered in

chromosome domains and are reduced in telomeric regions

and the vicinity of centromeres [10,11].

Local distribution of initiation sites

DSBs occur in highly localized regions and spread over

70–250 bp (reviewed in [7]). DNA sequence analysis reveals

no unique conserved consensus sequences, although a

degenerate 50-bp motif partly correlates with DSB sites.

However, one common feature is that DSBs are located in

accessible regions of the chromatin next to either promoters or binding sites for transcription factors (reviewed

in [12– 14]). Based on two studies, DSB activity does not

correlate with local transcriptional activity, but depends

on transcription-factor binding (HIS4 in S. cerevisiae and

ade6-M26 in S. pombe). The constraint imposed by chromatin is also revealed by the activity of a Gal4–Spo11 fusion

protein, which induces high DSB levels in a region that

contains a Gal4-binding site and normally a low DSB

http://tigs.trends.com 0168-9525/$ - see front matter q 2003 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00201-4

Review

515

TRENDS in Genetics Vol.19 No.9 September 2003

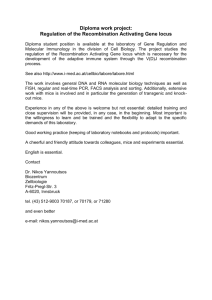

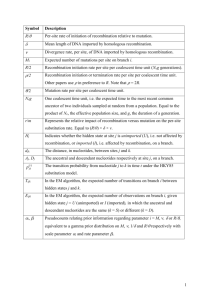

Box 1. Double-strand-break repair (DSBR) and synthesis-dependent strand-annealing (SDSA) models of meiotic

recombination

Two interacting duplexes from homologous chromosomes are shown

as black and red lines in Fig. I . Sister chromatids present at this stage

are not represented. Initiation occurs by double-strand break (DSB)

formation on the red chromatid. DSB ends are then degraded (Fig. Ia) to

generate long, 300 single-strand tails of several hundred base pairs. This

generates a gradient of single-strandedness in a population of cells,

with a higher level proximal to the break [77]. One single-strand invades

the homologous duplex (Fig. Ib) to form a heteroduplex and a D loop

that is extended by DNA synthesis. This has two possible outcomes.

In the DSB repair (DSBR) pathway, the D loop captures the second

30 end (Fig. Ic). DNA synthesis and ligation generate a double Holliday

junction [78 –80] with heteroduplex DNA flanking the DSB site [81]. This

recombination intermediate is resolved by the cleavage and ligation of

strands of same polarities at identical positions, which generates

crossover products. This pathway might also generate noncrossovers

(not shown). Mismatch repair of heteroduplexes can lead to either gene

conversion or restoration depending on the choice of the corrected

strand. Here, repair towards gene conversion is shown on both sides of

the initiation point. This is the major direction of repair for markers

located near the DSB site, probably because of the preferential removal

of strands with an available 30 end (i.e. strands from the initiating

duplex). Repair of heteroduplex DNA away from the DSB site might take

place on the opposite strand and lead to restoration.

In the synthesis-dependent strand-annealing (SDSA) pathway, the

D loop is disassembled by displacement of the newly synthesized

strand, which anneals with the other DSB end (Fig. Id). Repair of the

break is completed by DNA synthesis and ligation. Mismatch repair of

heteroduplex DNA generates gene conversion without crossover.

In both pathways, the process of mismatch repair is presented

arbitrarily at the last step. This is probably an oversimplified view

because mismatch repair itself might involve several pathways and act

at more than one step during the process [80]. Various alternatives

could be considered: for example, early repair of heteroduplex DNA at

the stage of D-loop formation could lead to conversion events on both

sides of the initiation event through the SDSA pathway. Little is known

about how and when Holliday junctions are processed, and when

mismatch repair takes place, although some data indicate that these

two events might be coordinated [82]. In the case shown, Holliday

junctions do not migrate from the region of initial heteroduplex DNA,

therefore crossover molecules have exchange points at the ends

of conversions tracts (shown as flags). More distal crossover points

might form if one or both Holliday junctions migrated away from the

initiation site.

Although most data that support this model result from studies

in yeast, the conservation of the major proteins involved indicates

that the main lines should be conserved in yeast and mammals [83].

DSB formation

3′

5′

3′

5′

(a)

5′ to 3′ resection

Heteroduplex

Strand-invasion, D-loop

formation, DNA synthesis

(dotted line)

(b)

DSBR

SDSA

Strand-displacement

Second end capture,

synthesis, ligation

(c)

(d)

Strand annealing,

synthesis, ligation

Holliday junction

resolution

Mismatch repair

Mismatch repair

Crossover

point

Crossover point

Gene conversion

tract

Gene conversion

with crossover

Gene conversion

tract

Gene conversion

without crossover

TRENDS in Genetics

Fig. I. Double-strand break repair (DSBR) and synthesis-dependent strand-annealing (SDSA) pathways. Reproduced with permission from [5].

activity [15]. However, some DSB sites do not seem to be

associated with the binding of transcription factors,

indicating that there might be alternative determinants

for accessibility to the recombination machinery. It has

been proposed that a chromatin-modification code contributes to the definition of DSB sites [13].

http://tigs.trends.com

Distribution of gene-conversion events

The presence of highly localized initiation sites that are

separated by regions that contain few detectable initiation

events allows the measurement of how recombination

extends from the initiation site. At several loci, genetic

analyses show that gene conversion frequencies decrease

516

Review

TRENDS in Genetics Vol.19 No.9 September 2003

Table 1. Analysis of gene-conversion gradients in yeasts and of a crossover gradient in mice

Schizosaccharomyces

pombe

Saccharomyces cerevisiac c

Highest markera

Lowest marker

Distanceb

P

Linear correlation within

99% confidence (P , 0.01)

Mean tract length (bp)

95% confidence interval

Mus musculus

ARG4 (1)

ARG4 (2)

HIS2

HIS4 (1)

HIS4 (2)

ade6

ura4-aim

Psmb9

1

0.02

1383

0.9975

Yes

1

0.12

2100

0.999

Yes

1

0.33

879

0.9988

Yes

1

0.44

2270

0.9997

No

1

0.19

1592

0.999

No

1

0.05

2357

0.9987

Yes

1

0.33

601

0.9987

Yes

1

0.03

790

0.9958

Yes

794

667 –981

2078

1420–3860

1679

1173– 2949

6562

Not determined

1963

Not determined

1591

1421 –3862

1484

946–3442

480

315 –1018

a

At each locus, the frequency of events for the highest frequency marker is normalized to 1.

Distance in base pairs between the highest and lowest frequency markers. The frequency of events as a function of distance follows an exponential law ( p value). References:

ARG4 (1), [60]; ARG4 (2), [18]; HIS2, [61]; HIS4 (1), [62]; HIS4 (2), M.F.F. Abdhulla and R.H. Borts, pers. commun.; ade6, [19]; ura4-aim, J. Kohli, pers. comm.; Psmb9, [35].

c

(1) and (2) refer to two independent experiments.

b

http://tigs.trends.com

co-conversion with a proximal promoter marker indicates

the presence of distal initiation events [17].

In agreement with the DSBR model and the processivity of heteroduplex repair, analysis at ARG4 and ade6

also show that most conversion tracts are continuous

[18,19]. However, discontinuous conversion tracts are

observed in other fungi, such as Neurospera crassa

[20,21] and Ascobolus immersus [22], which indicates

either alternative intermediates or alternative processing

of intermediates by the mismatch-repair machinery in

these species.

Distribution of crossing over

The model of DSBR allows alternatives to how and where

Holliday junctions could be resolved, and mapping geneconversion events does not directly address this issue.

There are at least two possibilities in terms of location:

either Holliday junctions are resolved in the area covered

by the conversion tracts or they migrate further away in

flanking regions. It should be emphasized that the location

of crossovers might be distinct from the actual point of

Holliday-junction resolution. Two studies performed in

S. cerevisiae, provide more information about this issue.

Symington et al. [23,24], used polymorphisms to select and

map crossovers in a 22 kb interval and two regions that

contained high densities of crossover were identified.

(a)

(b)

1.0

0.0015

0.8

Frequency

Relative frequency

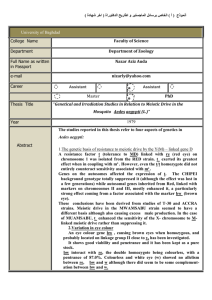

on both sides of the initiation site. The molecular mechanism responsible for this decrease, referred to as a

gradient of gene conversion, is debated. It could involve a

regulation of the directionality of mismatch repair, which

influences the relative frequencies of gene conversion and

restoration as a function of the distance from initiation, or

it might involve a regulation of heteroduplex length, or

both (Box 1). Data from several loci are reported in Table 1.

At each locus gene conversion frequencies of several

markers were measured. In each case, meiotic DSBs

were detected and the marker located closest to the DSB

site was found to have the highest frequency of gene

conversion. The relative frequencies of only the highest

(normalized to 1) and lowest markers are indicated in

the table.

When all markers tested are taken into account, the log

of the frequencies of gene conversion follows a linear

relationship as a function of distance with a 99% confidence interval in all cases tested except the HIS4 locus.

This exponential relationship is best explained by assuming that repair events that lead to gene conversion travel

from the initiation point with a fixed probability (1 2 p) of

stopping at a given position (n). The probability that a gene

conversion tract extends over a length L to position n from

initiation is: PðL ¼ nÞ ¼ pn ð1 2 pÞ ¼ (probability of reaching position n) £ (probability of stopping at position n).

Assuming independent processing of heteroduplexes on

either side of the DSB, as proposed in the DSBR model,

the length distribution of conversion tract is: PðCo ¼ n ¼

ðn þ 1Þpn ð1 2 pÞ2 ; with a the mean of (1 þ p)/(1 2 p) [16].

Examples of the distributions of gene-conversion frequencies and gene-conversion-tract lengths at the ARG4

locus are shown in Fig. 1. Applying this to other loci results

in a fairly homogeneous range of gene-conversion-tract

lengths in S. cerevisiae (except at the HIS4 locus) and

S. pombe. The means range from 800– 2000 bp at most loci.

At the HIS4 locus, the distribution of gene conversion is

not well fitted by an exponential law and the significance

of the predicted mean is therefore questionable. This

might reflect either some specific property of recombination in this region or that some of the events detected are

not initiated from DSBs located in the HIS4 promoter

region. The observation that a high proportion (, 50%)

of conversion events at a distal marker do not involve

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0

500 10001500200025003000

Distance (bp)

0.0010

0.0005

0

0

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000

Distance (bp)

TRENDS in Genetics

Fig. 1. (a) Distribution of gene conversion frequencies at the ARG4 locus. Values

are normalized to 1 for the marker with the highest frequency set at position 0.

Experimental values for eight markers are shown in pink. The best fit of the linear

correlation between the log of frequencies and distance is shown in blue

( p ¼ 0.99748). PðL $ nÞ ¼ p n : (b) Distribution of the gene-conversion tract length

assuming a bidirectional processing on either sides of the initiation point and an

exponential law of p ¼ 0.99748. PðCo ¼ nÞ-ðn þ 1Þp n ð1 2 pÞ2 : The mean of this

distribution is 794 bp.

Review

517

TRENDS in Genetics Vol.19 No.9 September 2003

DSBs were analyzed. Subsequent DSB analysis in this

region showed that the two regions with high crossover

density also have high levels of DSBs [25]. From the

sizes of the interval tested, it is likely that most crossovers occur within , 2 – 3 kb of their initiation site. Most

gene-conversion tracts detected are ,2 kb long and are

continuous. A minority (8%) of long conversion events

(4.5–12.0 kb) were also identified. Using a similar approach,

Borts et al. mapped gene conversion and crossing-over

association. As above, crossover mapped to the boarders

of conversion tracts in most cases, but positions of the

DSBs were not determined [26,27]. These data are consistent with a model in which the Holliday junctions do

not migrate from the region of initial asymmetric heteroduplex (Box 1).

By contrast, a recent comparison of DSB and crossover

density in large intervals in the S. pombe genome led

Young et al. [28] to propose that Holliday junctions migrate

and are resolved at long distances from their site of

initiation in this organism. However, in a study of gene

conversion and crossover association at the ade6 locus,

crossover separated from selected conversion events were

detected in one interval and found to represent only a

minority of events [19]. Further analyses are therefore

needed to determine the proportion of events that follow

this pathway in S. pombe [29].

Local distribution of recombination events in mammals

Local distribution of sites

Several recombination hot spots have been defined in

humans and mice. These are based on the higher density of

crossing over (relative to either adjacent regions or the

genome average) identified from pedigree analysis in

humans and screening recombinant in-crosses between

laboratory mouse strains. More recent studies have also

identified meiotic recombination hot spots and highresolution mapping of recombination events through

direct molecular analysis in humans and mice. The level

of precision, therefore, differs according to the methods

used. Table 2 summarizes those that are precisely located

on the physical map. Large differences are observed

between the activity of these hot spots, and their definition

is obviously relative. For example, recombination at Dna1

is three-fold lower than the genome average but about

seven-fold higher than surrounding regions.

In terms of location, of the 17 hot spots listed, nine are

intergenic (50 and 30 of genes), three are within introns, and

five are mapped at insufficient resolution to distinguish

intronic and exonic locations. Although analysis of DNA

sequences in these regions has identified no obvious

motifs, several properties have been noted [30,31]. Even

though not confined to transcription-promoter regions,

determinants for hot-spot localization in mammals might

Table 2. Hot spots in humans and mice

Hot spota

Frequency

(cM)

Interval

(Kb)

Fold above

genome

average

Location

Methods

Human

MS32

0.04

1.5

30

Intergenic, next to minisatellite

CEB1

0.16

2

$ 70

Intergenic, next to minisatellite

b-Globin

0.9

11

90

Intergenic, 50 of b globin

PGM1

CMT1a

1.7

0.0015

58

1.4

30

1.2

Intragenic, intron or exon

Intergenic

DNA1

0.0005

1.9

0.3

Intergenic, 50 of DNA

DNA2

0.0037

1.3

3

Intergenic, 30 of DNA, next Alu

DNA3

0.13

1.2

120

Intergenic, 30 of DNA, next Alu

DMB1

0.0031

1.8

2

Intragenic, intron or exon

DMB2

0.028

1.2

30

Intergenic, 30 of DMB

TAP2

0.0058

1

10

Intragenic, intron

PAR1

0.3

3.9

90

Intragenic, intron or exon

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Pedigree analysis and single

sperm analysis

Pedigree analysis

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Pedigree analysis and direct

molecular detection

Mouse

Ea

Eb

Psmb9

0.9

0.1

1

0.4

4

1.8

3750

40

930

Intragenic, intron

Intragenic, intron

Intergenic, 30 of Psmb9

Gc7

Pb

Unknown

1.5

2.4

5.3

Unknown

470

Intragenic, intron or exon

Intragenic, intron or exon

a

Genetic crosses

Genetic crosses

Genetic crosses and direct

molecular detection

Genetic crosses

Genetic crosses

Locus Link databaseb

HBB; locus ID, 64162

PGM1; locus ID, 5236

CMT1A; locus ID, 1248

HLA-DOA; locus ID, 3111

HLA-DOA; locus ID, 3111

HLA-DOA; locus ID, 3111

HLA-DMB; locus ID, 3109

HLA-DMB; locus ID, 3109

Tap2; locus ID, 6891

Shox; locus ID, 6473

H2-Ea; locus ID, 14968

H2-Eb1; locus ID, 14969

Psmb9; locus ID, 16912

D17H6S56E-3; locus ID, 27762

H2-Pb; locus ID, 15004

For each hot spot, the frequency of crossing-over is given in cM in the interval that defines the hot spot. The increase relative to the genome average is calculated taking a

value of 0.89 cM Mb21 for human [63] and 0.6 cM Mb21 for mouse [64]. These are average values for male and female recombination rates. The Cmt1a hot spot is a preferred

site for unequal exchanges. The methods used to define the locations and frequencies of the hot spots are indicated. References: MS32, [32]; CEB1, [4]; b-globin, [65– 67];

Pgm1, [68]; Cmt1a, [69]; Dna1, Dna2, Dna3, Dmb1 and Dmb2, [33]; Tap2, [30]; Par1, [70]; Ea, [71]; Eb, [72,73]; Psmb9, [35,74,75]; Gc7, [76]; Pb [31].

b

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/LocusLink

http://tigs.trends.com

Review

TRENDS in Genetics Vol.19 No.9 September 2003

share common features with those described in yeast, such

as chromatin accessibility. To what extent gene-regulatory

elements and transcription factors play a role in this

localization is currently unknown.

Local distribution of events

Direct molecular detection of recombination events was

developed by A. Jeffreys group to study minisatellite

rearrangements that take place at a high rate during

meiosis. This strategy allows the selective amplification of

recombinant molecules by PCR. In minisatellite regions,

the analysis of events either with or without the exchange

of flanking markers indicated the existence of two pathways, the DSBR and SDSA pathways described in Box 1.

In addition, extensive polymorphisms have allowed the

mapping of minisatellite rearrangements that show the

presence of gene conversion and crossover gradients [4,32].

The same approach has been used to study some crossover

hot spots that are not associated with minisatellites in

humans and mice (Table 2). Although the activities of

these hot spots differ by up to several-hundred-fold, they

share common features, such as clustering of crossovers in

a small interval (1 –3 kb) and nonrandom distribution with

a central region of highest density. In addition, all recombinant molecules detected are simple exchanges with no

mosaicism.

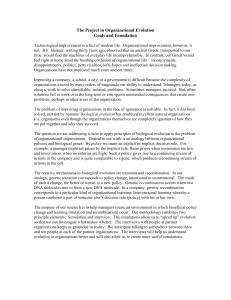

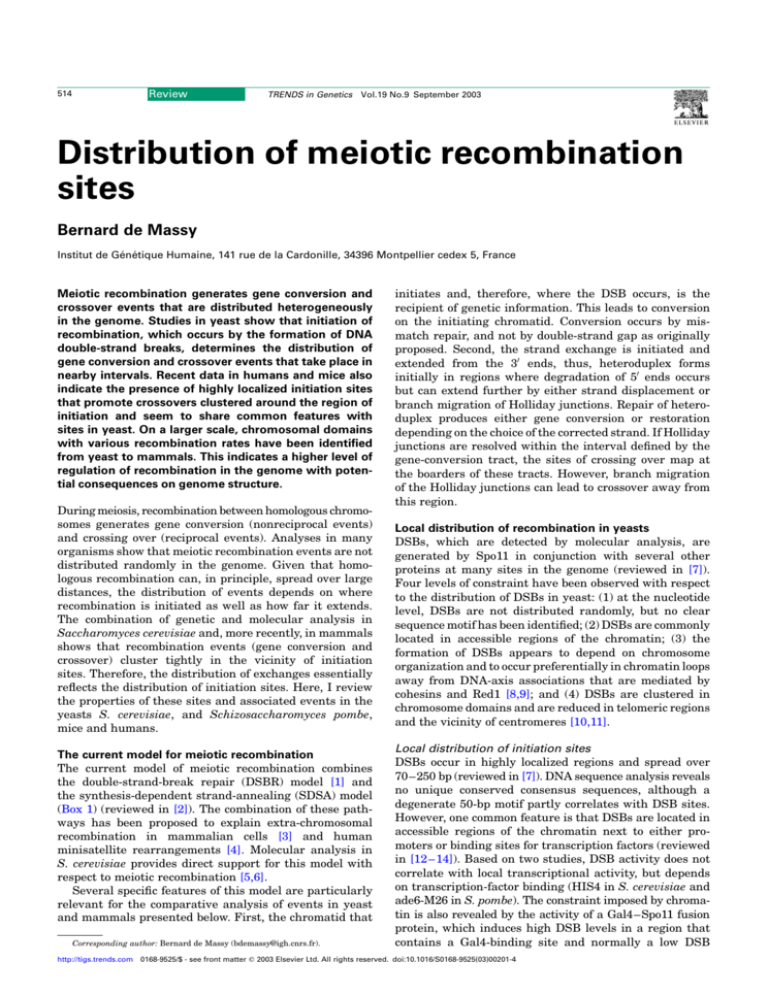

The distribution of crossovers at the mouse Psmb9 hot

spot is presented in Fig. 2. The properties of Psmb9 are

compatible with the presence of an initiation site that

induces recombination events that are repaired according

to the DSBR model, and where crossover points correspond

to the borders of gene-conversion tracts (Box 1). The

distribution of crossovers fits an exponential law on either

side of the central region, corresponding to a mean value

for tract sizes of 480 bp, which is slightly shorter than that

deduced from gene-conversion events in yeast (Table 1).

This observation of highly localized crossovers fits with

the analysis of linkage disequilibrium near hot spots in

humans. In the regions between hot spots [e.g. the 100 kb

interval between Dmb and Tap2 (Fig. 3a)], there is a strong

linkage, which indicates that few crossovers extend outside the hot-spot regions [33]. Two additional pieces of

information strongly support these hot spots as sites of

initiation. First, one prediction of the DSBR model is that

when only one homologous chromosome initiates, of the

two types of crossover molecules that can be recovered,

the exchange point of one will always be on one side of

the initiation site, and the other on the opposite side

(Box 1). In some heterozygous situations, such a bias has

been observed at the human Dna2 hot spot [34] and at the

mouse Psmb9 hot spot (F. Baudat and B. de Massy, pers.

commun.). Second, the presence of an initiation site

predicts a high frequency of gene-conversion events that

are not associated with a crossover. Recombinant molecules compatible with such events occur at the Psmb9

hot spot for a marker located in the central region. The

sizes of the gene-conversion events (without crossover

in the interval tested) recovered in this analysis were

short (, 500 bp), which is compatible with the analysis of

crossover distribution discussed above [35].

http://tigs.trends.com

Crossover frequency (cM Mb–1)

518

1500

210 bp

1000

500

100

T/C T/C

TaqI

T/C T/A

BsrFI StyI

(A)8/9

SphI

Eco57I

TRENDS in Genetics

Fig. 2. Distribution of crossovers at the Psmb9 hot spot in mice. Recombinant

molecules were selected by allele-specific PCR using primers 3 kb apart. All events

detected map within the TaqI –Eco57I interval (1.8 Kb) in which the average polymorphism is 0.65%. The crossover frequency relative to distance (cM Mb21) is

given for the intervals analysed, based on the analysis of 69 independent events

(38 and 31 of each type of exchange). The interval with the highest crossover density is defined by the 210-bp BsrFI– StyI region and corresponds to the center of

the initiation site. The T ! C, T ! A and (A)8/9 polymorphisms are indicated. Data

reproduced with permission from [35].

Global distribution of recombination in yeasts

The extensive molecular analyses in yeasts reveal that

DSB sites cluster into chromosomal domains. For instance,

on S. cervisiae chromosome III (300 kb long), two separate

domains (,50 kb each) with high DSB levels can be

identified [10,11]. The influence of domains is well illustrated by the correlation between the level of DSB of an

inserted sequence and the global DSB level of the domain

where it is inserted [36]. Components that define these

domains are unknown. In addition, centromeric regions

and telomeres (10 – 20 kb proximal) are repressed for DSB

formation.

Global distribution of recombination in mammals

High-resolution analysis of a 200 KB interval in the major

histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II region reveals

six hot spots (Table 2), the activities of which varies from

0.3 to 110 cM Mb21. These hot spots cluster in three

regions and are separated by 50 – 100 kb (Fig. 3a). In these

intervals, the values of recombination frequencies are a

rough estimate based on linkage disequilibrium (LD)

analysis. The crossovers in the hot-spot regions, which

cover , 10% of the whole interval, account for . 95% of

crossover events. This analysis illustrates clearly the high

discontinuity of distribution of recombination rates and a

surprisingly high level of variation in recombination rates

between hot spots (up to 400 fold).

At a lower resolution, crossover distribution in the

whole MHC (3.5 Mb) was analyzed using pedigree and

single-sperm analysis [37]. Markers 30 –200 kb apart

define 30 intervals in which crossover density varies

from 0.15 to 2.50 cM Mb21 with an average of

0.49 cM Mb21. This is slightly lower than the male average

(0.85 cM Mb21 from [38]) (Fig. 3b). Six regions are ‘hotter’

Review

TRENDS in Genetics Vol.19 No.9 September 2003

(a)

1000

cM Mb–1

100

10

1

3 mcM

0.1

3 mcM

4 mcM

?

0.01

(b)

3.0

Frequency (cM Mb–1)

0

2.5

50

100

kb

150

TAP2

PSMB9

TAP1

PSMB8

DMA

DMB

DNA

RING3

0

200

centromeric and telomeric regions are, on average, systematically cold and hot, respectively. However, there are large

sex differences in these regions, with, in general, a higher

frequency of recombination near centromeres in females

and a higher frequency of recombination near telomeres in

males. Although the average recombination rate in females

is 1.65 times higher than in males, some regions in chromosome arms can be hotter in males than females. In fact,

the correlation (R value) between male and female rates

is 0.57, which indicates that a large amount of the control

of the distribution of recombination along chromosomes

is regulated by factors other than the primary DNA

sequence [38]. These chromosome-wide variations are also

described at the cytological level in humans and mice,

through the analysis of chiasmata and late recombination

nodules [42,43].

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

Distance (Kb)

Class II

(c)

Chromosome 6

3

Frequency (cM Mb–1)

519

2

1

0

c

MHC

0

50

100

Mb

150

200

TRENDS in Genetics

Fig. 3. Recombination hot spots on human chromosome 6. (a) High-resolution

mapping of crossover within 200 kb in the major histocompatibility complex

(MHC) class II region. Recombination frequencies were measured by direct

molecular detection in the six intervals showing peaks of recombination rates

(Dna1, Dna2 and Dna3 near the DNA gene, Dmb1 and Dmb2 near the DMB gene

and Tap2). These values are from male meiosis. Between these sites, recombination rates were approximated from linkage disequilibrium studies. (b) Mapping

crossovers in the MHC region by sperm typing. Each point represents the centre of

the intervals (average of 12 individuals). The position of the 200 kb interval of the

class II genes in (a) is shown as a solid line, the remainder of this region is shown

as a dotted line. (c) Mapping crossovers on human chromosome 6 (male and

female). Data are plotted with 3 Mb windows, moved by 1 Mb steps. The positions

of the MHC and the centromere (c) are shown. Data reproduced with permission

from: (a), [33]; (b), [37]; and (c), [38].

than average, one of which includes the strongest hot-spot

defined at high resolution (Dna3). At still lower resolution,

the human and mouse genetic maps reveal Mb fluctuations in recombination rates [38 – 41]. These variations

are shown for human chromosome 6, which contains the

MHC region (Fig. 3c). On this chromosome, recombination

rates vary from 0.1 to 3.0 cM Mb21 with an average of

1 cM Mb21, which is close to the genome average in this

study (1.13 cM Mb21). It is likely that these variations

are caused by a combination of variations in density and

levels of activity of initiation sites in these intervals. The

http://tigs.trends.com

GC content and the distribution of recombination

The analysis of DSB distribution in S. cerevisiae shows a

correlation between DSB activity and GC content: domains

with high levels of DSB correspond to GC-rich domains

[10,11]. Furthermore, DSB activities of a DNA fragment

inserted at various locations on yeast chromosome III

correlate with local GC content [44]. In humans, two LD

studies indicate a correlation between high GC content

and elevated recombination rates [45,46]. However, estimation of recombination rates based on LD analysis is

subject to several caveats and should be taken with caution

[47]. Nevertheless, the correlation between recombination

density and GC is observed from the complete human

genetic map [48,49], and has also been deduced from

immunolocalization of recombination nodules [50]. GC-rich

regions are organized into chromosome domains, also

identified as isochores [51], which correspond to gene-rich

R bands. Many properties distinguish GC-rich from GC-poor

domains, such as replication timing and the frequency of

repeated sequences [52,53]. It is important to note that

although the correlation is significant, the variation in

GC content accounts for only a small part of the variation

in recombination rates (17%, R2 ¼ 0.17) [38]. The detailed

analysis of recombination in the human MHC show no

correlation between recombination rate and GC content:

the sharp increase in the proportion of GC residues in class

II compared to class III genes does not cause a difference in

recombination rates on either side of this transition

(0.66 cM Mb21 in the class II region, intervals Dpb1 to

Notch4, and 0.46 cM Mb21 in the class III region, intervals

Notch4 to MicB) [37]. Furthermore, in the MHC class II

region, of the three crossover clusters that have been

mapped at high resolution (Dna3, Dmb2 and Tap2), only

one (Tap2) corresponds to a region with a higher than

average GC content. In this region, three GC peaks are

located in cold intervals for recombination (B. de Massy

and L. Duret, unpublished). Given that these hot spots are

in regions with relatively low GC content, one can conclude

that a high level of recombination activity does not require

a GC-rich domain or a high local GC content. The correlation observed at high resolution in yeast is, therefore, not

universal.

Whatever the correlation observed, it is important to

determine whether it is either a cause or a consequence

520

Review

TRENDS in Genetics Vol.19 No.9 September 2003

(or both) of the recombination activity. Several studies

address this issue, taking into account several parameters

of genome evolution and considering either selectionist or

neutralist models (reviewed in [54]). Although selectionist

models related to features such as gene organization

and/or chromatin properties have not been tested, two

observations favor the neutralist model. First, in yeast, the

correlation between DSB levels and GC content is higher

when the GC content at the third base of a codon (GC3) is

used as parameter, rather than GC values as a whole [55].

Second, in mice, the recent translocation of a gene into the

pseudo-autosomal region correlates with an increase in

GC3 from 50 to 73%. This indicates strongly that elevated

GC content is a consequence and not the cause of recombination activity in this case [56]. Two processes have,

therefore, been proposed to explain a neutral effect: either

a mutation bias or a gene-conversion bias [55,57,58]. The

hypothesis that recombination contributes to changes in

GC content also needs to account for the observation that

recombination events are highly localized and, therefore,

explain how, for instance, a local gene-conversion bias

could affect the GC composition over large chromosome

domains. Given the time-scale over which these changes

are expected to take place, the validation of such a hypothesis might require understanding the distribution,

evolution and possible movement of recombination sites

in the genome. Indeed, recombination sites raise a paradoxical situation: given the mechanism of DSBR, sequences

on the active chromosome will be replaced by that of the

less active one, which would be expected to lead to the loss

of initiation sites [59]. However, given the complexity of

determinants that influence recombination rates described

above, and that many of these determinants do not reside

in the area where recombination takes place, the preferential loss of sequences on the initiating chromosome

might only marginally affect its recombination activity.

Conclusions

Many aspects of the mechanism of meiotic recombination

have been identified in yeast, where the initiating lesion

is a DSB. Repair by the DSBR pathway leads to gene

conversion and crossing-over, and repair by the SDSA

pathway leads to gene conversion without crossover. The

main lines of this mechanism are thought to be conserved

in mammals. In S. cerevisiae, analysis of DSBs shows that

initiation takes place in open chromatin. Genetic analysis

shows that both gene conversion and crossover cluster

tightly within a few Kb of the DSB. Comparison of genetic

and DSB data in S. pombe indicates a different situation in

which reciprocal exchanges take place far (. 10 kb) away

from initiation. Although DSBs have not yet been identified in mammals, several crossover hot-spot regions are

likely to correspond to preferred initiation sites. In such

regions, crossovers are tightly clustered and follow a

distribution in agreement with the DSBR pathway, similar

to that described in S. cerevisiae. The heterogeneous

distribution of these hot spots creates large regions with

low levels of recombination separated by small intervals

with hot-spot activities and results in up to thousand-fold

variations in recombination rates. At the chromosome

level in both yeast and mammals, a second layer of

http://tigs.trends.com

regulation of recombination is apparent from the presence

of large domains with either high or low levels of recombination. One of the proposed consequences of heterogeneous distribution of recombination, which is supported

by data from yeast and mice, is the increase in GC content

in regions with high levels of recombination. These interpretations provide new ideas and predictions for mechanistic aspects of meiotic recombination.

Acknowledgements

I thank F. Baudat, J. Buard, L. Duret and M. Lichten for critical reading of

the manuscript, and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the

Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique and the Association pour la Recherche

contre le Cancer for supporting my work.

References

1 Szostak, J.W. et al. (1983) The double-strand-break repair model for

recombination. Cell 33, 25 – 35

2 Pâques, F. and Haber, J.E. (1999) Multiple pathways of recombination

induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 349 – 404

3 Belmaaza, A. and Chartrand, P. (1994) One-sided invasion events in

homologous recombination at double-strand breaks. Mutat. Res. 314,

199 – 208

4 Buard, J. et al. (2000) Meiotic recombination and flanking marker

exchange at the highly unstable human minisatellite CEB1 (D2S90).

Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 333 – 344

5 Allers, T. and Lichten, M. (2001) Differential timing and control of

noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell 106,

47 – 57

6 Hunter, N. and Kleckner, N. (2001) The single-end invasion: an

asymmetric intermediate at the double-strand break to doubleholliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. PG. Cell 106,

59 – 70

7 Keeney, S. (2001) Mechanism and control of meiotic recombination

initiation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 52, 1 – 53

8 Blat, Y. and Kleckner, N. (1999) Cohesins bind to preferential sites

along yeast chromosome III, with differential regulation along arms

versus the centric region. Cell 98, 249 – 259

9 Blat, Y. et al. (2002) Physical and Functional Interactions among Basic

Chromosome Organizational Features Govern Early Steps of Meiotic

Chiasma Formation. Cell 111, 791– 802

10 Baudat, F. and Nicolas, A. (1997) Clustering of meiotic double-strand

breaks on yeast chromosome III. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94,

5213– 5218

11 Gerton, J.L. et al. (2000) Inaugural article: global mapping of meiotic

recombination hotspots and coldspots in the yeast Saccharomyces

cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 11383– 11390

12 Nicolas, A. (1998) Relationship between transcription and initiation

of meiotic recombination: toward chromatin accessibility. Proc. Natl.

Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 87 – 89

13 Petes, T.D. (2001) Meiotic recombination hot spots and cold spots.

Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 360 – 369

14 Davis, L. and Smith, G.R. (2001) Meiotic recombination and chromosome segregation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc. Natl. Acad.

Sci. U. S. A. 98, 8395 – 8402

15 Pecina, A. et al. (2002) Targeted stimulation of meiotic recombination.

Cell 111, 173– 184

16 Hilliker, A.J. et al. (1994) Meiotic gene conversion tract length

distribution within the rosy locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics

137, 1019– 1026

17 Porter, S.E. et al. (1993) Genetic evidence that the meiotic recombination hotspot at the HIS4 locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae does not

represent a site for a symmetrically processed double-strand break.

Genetics 134, 5 – 19

18 Schultes, N.P. and Szostak, J.W. (1990) Decreasing gradients of gene

conversion on both sides of the initiation site for meiotic recombination

at the ARG4 locus in yeast. Genetics 126, 813– 822

19 Grimm, C. et al. (1994) M26 recombinational hotspot and physical

conversion tract analysis in the ade6 gene of Schizosaccharomyces

pombe. Genetics 136, 41– 51

Review

TRENDS in Genetics Vol.19 No.9 September 2003

20 Bowring, F.J. and Catcheside, D.E. (1998) Analysis of conversion tracts

associated with recombination events at the am locus of Neurospora

crassa. Curr. Genet. 34, 43 – 49

21 Yeadon, P.J. and Catcheside, D.E. (1998) Long, interrupted conversion

tracts initiated by cog in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 148, 113 – 122

22 Langin, T. et al. (1988) Reciprocal exchanges instigated by large

heterologies in the b2 gene of ascobolus are not associated with long

adjacent hybrid DNA stretches. Genetics 119, 329 – 336

23 Symington, L.S. and Petes, T.D. (1988) Expansions and contractions of

the genetic map relative to the physical map of yeast chromosome III.

Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 595 – 604

24 Symington, L.S. et al. (1991) Genetic analysis of a meiotic recombination hotspot on chromosome III of Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Genetics 128, 717 – 727

25 Wu, T-C. and Lichten, M. (1994) Meiosis-induced double-strand break

sites determined by yeast chromatin structure. Science 263, 515– 518

26 Borts, R.H. and Haber, J.E. (1987) Meiotic recombination in yeast:

alteration by multiple heterozygosities. Science 237, 1459– 1465

27 Borts, R.H. and Haber, J.E. (1989) Length and distribution of meiotic

gene conversion tracts and crossovers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Genetics 123, 69 – 80

28 Young, J.A. et al. (2002) Meiotic recombination remote from prominent

DNA break sites in S. pombe. Mol. Cell 9, 253– 263

29 Smith, G.R. (2001) Homologous recombination near and far from DNA

breaks: alternative roles and contrasting views. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35,

243 – 274

30 Jeffreys, A.J. et al. (2000) High resolution analysis of haplotype

diversity and meiotic crossover in the human TAP2 recombination

hotspot. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 725– 733

31 Isobe, T. et al. (2002) Molecular characterization of the Pb recombination hotspot in the mouse major Histocompatibility Complex class II

region. Genomics 80, 229 – 235

32 Jeffreys, A.J. et al. (1998) High-resolution mapping of crossovers

in human sperm defines a minisatellite-associated recombination

hotspot. Mol. Cell 2, 267 – 273

33 Jeffreys, A.J. et al. (2001) Intensely punctate meiotic recombination in

the class II region of the major histocompatibility complex. Nat. Genet.

29, 217 – 222

34 Jeffreys, A.J. and Neumann, R. (2002) Reciprocal crossover asymmetry and meiotic drive in a human recombination hot spot. Nat.

Genet. 31, 267 – 271

35 Guillon, H. and De Massy, B. (2002) An initiation site for meiotic

crossing-over and gene conversion in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 32,

296 – 299

36 Borde, V. et al. (1999) Use of a recombination reporter insert to define

meiotic recombination domains on chromosome III of Saccharomyces

cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 4832– 4842

37 Cullen, M. et al. (2002) High-resolution patterns of meiotic recombination across the human major histocompatibility complex. Am.

J. Hum. Genet. 71, 759 – 776

38 Kong, A. et al. (2002) A high-resolution recombination map of the

human genome. Nat. Genet. 31, 241 – 247

39 Nachman, M.W. and Churchill, G.A. (1996) Heterogeneity in rates of

recombination across the mouse genome. Genetics 142, 537 – 548

40 Broman, K.W. et al. (1998) Comprehensive human genetic maps:

individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. Am. J. Hum.

Genet. 63, 861 – 869

41 Yu, K. and Feingold, E. (2001) Estimating the frequency distribution of

crossovers during meiosis from recombination data. Biometrics 57,

427 – 434

42 Lawrie, N.M. et al. (1995) Chiasma frequency, distribution and

interference maps of mouse autosomes. Chromosoma 104, 308 – 314

43 Barlow, A.L. and Hulten, M.A. (1998) Crossing over analysis at

pachytene in man. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 6, 350 – 358

44 Petes, T.D. and Merker, J.D. (2002) Context dependence of meiotic

recombination hotspots in yeast. The relationship between recombination activity of a reporter construct and base composition. Genetics

162, 2049 – 2052

45 Eisenbarth, I. et al. (2000) An isochore transition in the NF1 gene

region coincides with a switch in the extent of linkage disequilibrium.

Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 873 – 880

46 Eisenbarth, I. et al. (2001) Long-range sequence composition mirrors

http://tigs.trends.com

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

521

linkage disequilibrium pattern in a 1.13 Mb region of human

chromosome 22. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 2833– 2839

Phillips, M.S. et al. (2003) Chromosome-wide distribution of haplotype

blocks and the role of recombination hot spots. Nat. Genet. 33, 382 – 387

Yu, A. et al. (2001) Comparison of human genetic and sequence-based

physical maps. Nature 409, 951 – 953

Fullerton, S.M. et al. (2001) Local rates of recombination are positively

correlated with GC content in the human genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18,

1139– 1142

Plug, A.W. et al. (1996) Presynaptic association of Rad51 protein with

selected sites in meiotic chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93,

5920– 5924

Bernardi, G. (2000) Isochores and the evolutionary genomics of

vertebrates. Gene 241, 3 – 17

Tenzen, T. et al. (1997) Precise switching of DNA replication timing in

the GC content transition area in the human major histocompatibility

complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 4043 – 4050

Jabbari, K. and Bernardi, G. (1998) CpG doublets, CpG islands and Alu

repeats in long human DNA sequences from different isochore

families. Gene 224, 123 – 127

Eyre-Walker, A. and Hurst, L.D. (2001) The evolution of isochores.

Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 549 – 555

Birdsell, J.A. (2002) Integrating genomics, bioinformatics, and

classical genetics to study the effects of recombination on genome

evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19, 1181– 1197

Perry, J. and Ashworth, A. (1999) Evolutionary rate of a gene affected

by chromosomal position. Curr. Biol. 9, 987– 989

Wolfe, K.H. et al. (1989) Mutation rates differ among regions of the

mammalian genome. Nature 337, 283 – 285

Galtier, N. et al. (2001) GC-content evolution in mammalian genomes:

the biased gene conversion hypothesis. Genetics 159, 907 – 911

Boulton, A. et al. (1997) The hotspot conversion paradox and the

evolution of meiotic recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94,

8058– 8063

Nicolas, A. et al. (1989) An initiation site for meiotic gene conversion in

the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 338, 35 – 39

Malone, R.E. et al. (1992) A meiotic gene conversion gradient opposite

to the direction of transcription. Nature 359, 154 – 155

White, M.A. et al. (1992) A promoter deletion reduces the rate of

mitotic, but not meiotic, recombination at the HIS4 locus in yeast.

Curr. Genet. 21, 109 – 116

Gyapay, G. et al. (1994) The 1993-94 Genethon human genetic linkage

map. Nat. Genet. 7, 246 – 339

Blake, J.A. et al. (2000) The Mouse Genome Database (MGD):

expanding genetic and genomic resources for the laboratory mouse.

The Mouse Genome Database Group. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 108 – 111

Smith, R.A. et al. (1998) Recombination breakpoints in the human

beta-globin gene cluster. Blood 92, 4415– 4421

Schneider, J.A. et al. (2002) Direct measurement of the male

recombination fraction in the human beta- globin hot spot. Hum.

Mol. Genet. 11, 207 – 215

Chakravarti, A. et al. (1984) Nonuniform recombination within the

human beta-globin gene cluster. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 36, 1239– 1258

Yip, S.P. et al. (1999) Mapping recombination hotspots in human

phosphoglucomutase (PGM1). Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 1699– 1706

Han, L.L. et al. (2000) Unequal exchange at the charcot-marie-tooth

disease type 1A recombination hot-spot is not elevated above the

genome average rate. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 1881 – 1889

May, C.A. et al. (2002) Crossover clustering and rapid decay of linkage

disequilibrium in the Xp/Yp pseudoautosomal gene SHOX. Nat. Genet.

31, 272 – 275

Khambata, S. et al. (1996) Ea recombinational hot spot in the mouse

major histocompatibility complex maps to the fourth intron of the Ea

gene. Genome Res. 6, 195 – 201

Kobori, J.A. et al. (1986) Molecular analysis of the hotspot of

recombination in the murine major histocompatibility complex.

Science 234, 173– 179

Zimmerer, E.J. and Passmore, H.C. (1991) Structural and genetic

properties of the Eb recombinational hotspot in the mouse. Immunogenetics 33, 132 – 140

Shiroishi, T. et al. (1990) Recombinational hotspot specific to female

meiosis in the mouse major histocompatibility complex. Immunogenetics 31, 79 – 88

522

Review

TRENDS in Genetics Vol.19 No.9 September 2003

75 Shiroishi, T. et al. (1991) Genetic control of sex-dependent meiotic

recombination in the major histocompatibility complex of the mouse.

EMBO J. 10, 681 – 686

76 Snoek, M. et al. (1998) Molecular analysis of the major MHC

recombinational hot spot located within the G7c gene of the murine

class III region that is involved in disease susceptibility. J. Immunol.

160, 266 – 272

77 Sun, H. et al. (1991) Extensive 3(-overhanging, single-stranded DNA

associated with the meiosis-specific double-strand breaks at the arg4

recombination initiation site. Cell 64, 1155– 1161

78 Collins, I. and Newlon, C.S. (1994) Meiosis-specific formation of joint

DNA molecules containing sequences from homologous chromosomes.

Cell 76, 65 – 75

79 Schwacha, A. and Kleckner, N. (1994) Identification of joint molecules

that form frequently between homologs but rarely between sister

chromatids during yeast meiosis. Cell 76, 51 – 63

80 Schwacha, A. and Kleckner, N. (1995) Identification of double

Holliday junctions as intermediates in meiotic recombination. Cell

83, 783 – 791

81 Allers, T. and Lichten, M. (2001) Intermediates of yeast meiotic

recombination contain heteroduplex dna. Mol. Cell 8, 225 – 231

82 Alani, E. et al. (1994) Interaction between mismatch repair and genetic

recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 137, 19– 39

83 Cohen, P.E. and Pollard, J.W. (2001) Regulation of meiotic recombination and prophase I progression in mammals. BioEssays 23,

996– 1009

News & Features on BioMedNet

Start your day with BioMedNet’s own daily science news, features, research update articles and special reports. Every two weeks,

enjoy BioMedNet Magazine, which contains free articles from Trends, Current Opinion, Cell and Current Biology. Plus, subscribe to

Conference Reporter to get daily reports direct from major life science meetings.

http://news.bmn.com

Here is what you will find in News & Features:

Today’s News

Daily news and features for life scientists.

Sign up to receive weekly email alerts at http://news.bmn.com/alerts

Special Report

Special in-depth report on events of current importance in the world of the life sciences.

Research Update

Brief commentary on the latest hot papers from across the Life Sciences, written by laboratory researchers chosen by the editors of

the Trends and Current Opinions journals, and a panel of key experts in their fields.

Sign up to receive Research Update email alerts on your chosen subject at http://update.bmn.com/alerts

BioMedNet Magazine

BioMedNet Magazine offers free articles from Trends, Current Opinion, Cell and BioMedNet News, with a focus on issues of general

scientific interest. From the latest book reviews to the most current Special Report, BioMedNet Magazine features Opinions, Forum

pieces, Conference Reporter, Historical Perspectives, Science and Society pieces and much more in an easily accessible format. It

also provides exciting reviews, news and features, and primary research. BioMedNet Magazine is published every 2 weeks.

Sign up to receive weekly email alerts at http://news.bmn.com/alerts

Conference Reporter

BioMedNet’s expert science journalists cover dozens of sessions at major conferences, providing a quick but comprehensive report

of what you might have missed. Far more informative than an ordinary conference overview, Conference Reporter’s easy-to-read

summaries are updated daily throughout the meeting.

Sign up to receive email alerts at http://news.bmn.com/alerts

http://tigs.trends.com