Anti-Racism – What Works? - Office of Multicultural Interests

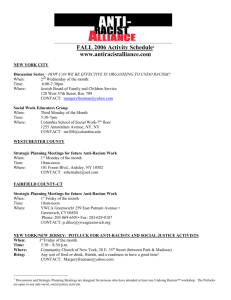

advertisement