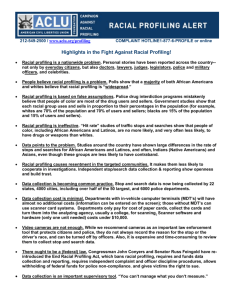

Undocumented Criminal Procedure

advertisement