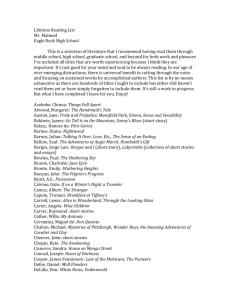

verdugoi88182 - University of Texas Libraries

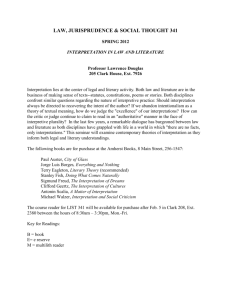

advertisement