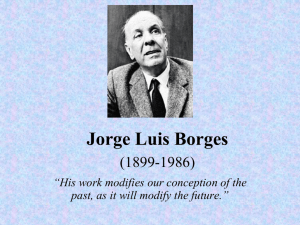

The Minds I Chapter 01 Borges and I - Jorge Luis

advertisement

1 Jorge Luis Borges Borges and I The other one, the one called Borges, is the one things happen to. I walk through the streets of Buenos Aires and stop for a moment, perhaps mechanically now, to look at the arch of an entrance hall and the grillwork on the gate. I know of Borges from the mail and see his name on a list of professors or in a biographical dictionary. I like hourglasses, maps, eighteencentury typography, the taste of coffee and the prose of Stevenson; he shares these preferences, but in a vain way that turns them into the attributes of an actor. It would be an exaggeration to say that ours is a hostile relationship. I live, let myself go on living. so that Borges may contrive his literature, and this literature justifies me. It is no effort for me to confess that he has achieved some valid pages, but those pages cannot save me, perhaps because what is good belongs to no one, not even to him, but rather to the language and to tradition. Besides I am destined to perish, definitively, and only some instant of myself can survive in him. Little by little, I am giving over everything to him, though I am quite aware of his perverse custom of falsifying and magnifying things. Spinoza knew that all things long to persist in their being; the stone eternally wants to be a stone, and the tiger a tiger. I shall remain in Borges, not in myself (if it is true that I am someone), but I recognize myself les in his books than in many others or in the laborious strum“Borges and ,I by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by James E. Irby, from Labyrinths; Selected Stories and Other Writings, edited by Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby. Copyright © 1962 by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions, New York. Borges and I 20 ming of a guitar. Years ago I tried to free myself from him and went from the mythologies of the suburbs to the games with time and infinity, but those games belong to Borges now and I shall have to imagine other things. Thus my life is a flight and I lose everything and everything belongs to oblivion, or to him. I do not know which of us has written this page. Reflections Jorge Luis Borges, the great ArgentinIan writer, has a deserved international reputation, which creates a curious effect. Borges seems to himself to be two people, the public personage and the private person. His fame magnifies the effect, but we all can share the feeling, as he knows. You read your name on a list, or see a candid photograph of yourself, or overhear others talking about someone and suddenly realize it is you. Your mind must leap from a third-person perspective -- “he” or “she” – to a first-person perspective – “I.” Comedians have long known how to exaggerate this leap: the classic “double-take” in which say, Bob Hope reads in the morning newspaper that Bob Hope is wanted by the police, casually comments on this fact, and then jumps up in alarm: “That’s me!” While Robert Burns may be right that it is a gift to see ourselves as others see us, it is not a condition to which we could or should aspire at all times. In fact, several philosophers have recently presented brilliant arguments to show that there are two fundamentally and irreducibly different ways of thinking for ourselves. (See “Further Reading” for the details.) The arguments are quite technical, but the issues are fascinating and can be vividly illustrated. Pete is waiting in line to pay for an item in a department store, and he notices that there is a closed-circuit television monitor over the counter – one of the store’s measures against shoplifters. As watches the jostling crowd of people on the monitor, he realizes that the person on the left side of the screen in the overcoat carrying the large paper bag is having his pocket picked by the person behind him. Then, as he raises his hand to his mouth in astonishment, he notices that the victim’s hand is moving to his mouth in just the same way. Pete suddenly realizes Borges and I 21 that he is the person whose pocket is being picked! This dramatic shift is a discovery; Pete comes to know something he didn’t know a moment before, and of course it is important. Without the capacity to entertain the sorts of thoughts that now galvanize him into defensive action, he would hardly be capable of action at all. But before the shift, he wasn’t entirely ignorant, of course; he was thinking about “the person in the overcoat” and seeing that the person was being robbed, and since the person in the overcoat is himself, he was thinking about himself. But he wasn’t thinking about himself as himself; he wasn’t thinking about himself “in the right way.” For another example, imagine someone reading a book in which a descriptive noun phrase of, say, three dozen words in the first sentence of a paragraph portrays an unnamed person of initially indeterminate sex who is performing an everyday activity. The reader of that book, on reading the given phrase, obediently manufactures in his or her mind’s eye a simple, rather vague mental image of a person involved in some mundane activity. In the next few sentences, as more detail is added to the description, the reader’s mental image of the whole scenario comes into a little sharper focus. Ten at a certain moment, after the description has gotten quite specific, something suddenly “clicks,” and the reader gets an eerie sense that he or she is the very person being described! “How stupid of me not to recognize earlier that I was reading about myself!” the reader muses, feeling a little sheepish, but also quite tickled. You can probably imagine such a thing happening, but to help you imagine it more clearly, just suppose that the book involved was The Mind’s I. There now – doesn’t your mental image of the whole scenario come into a little sharper focus? Doesn’t it all suddenly “click”? What page did you imagine the reader as reading? What paragraph? What thoughts might have crossed the reader’s mind? If the reader were a real person, what might he or she be doing right now? It is not easy to describe something of such special selfrepresentation. Suppose a computer is programmed to control the locomotion and behavious of a robot to which it is attached by radio links. (The famous “Shakey” at SRI International in California was so controlled.) The computer contains a representation of the robot and its environment, and as the robot moves around, the representation changes accordingly. This permits the computer program to control the robot’s activities with the aid of up-to-date information about the robot’s “body” and the environment it finds itself in. Now suppose the computer represents the robot as located in the middle of an empty room, and suppose you are Borges and I 22 Asked to “translate into English” the computer’s internal representation. Should it be “It (or he or Shakey) is in the centre of an empty room” or “I am in the centre of an empty room”? This question resurfaces in a different guise in Part IV of this book. D.C.D. D.R.H.