Our Manifest Destiny Bids Fair for Fulfillment

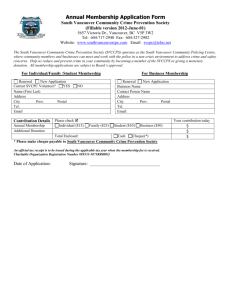

advertisement