Make Room for the Local - Association of American Colleges

advertisement

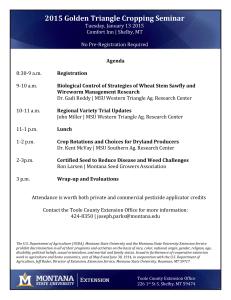

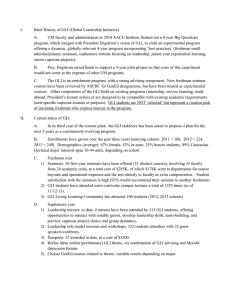

Make Room for the Local The Global Leadership Initiative Arlene Walker-Andrews & Cody Dems, Univ. of Montana “Almost 80% of the global population faces exposure to high threat levels of water insecurity.” - N. Uchtmann, Global-e • “Global” to Us • Complex • Across borders • Multi-faceted • Common to all people The Global Leadership Initiative (GLI) at the University of Montana creates an opportunity for students to ask some of the most pressing questions of the 21st century while gaining the skills necessary to find the answers. What is the Global Leadership Initiative? Exploring Global Problems Learning Leadership Skills Experiential Learning The Capstone Project The GLI Experience The GLI Student: Bridgette Preparation/MOL • Taken a small seminar on green cities (sustainability) • Gained a multi-disciplinary Experience/Capstone • Study cohousing in Denmark • Create a feasibility study perspective on this issue for cohousing in Missoula • Interacted with leadership • Bring this concept to cities role models across the U.S. Communication Place Make Room for the Local Arlene Walker‐Andrews and Cody Dems The University of Montana Presented at the meeting of the Association of American Colleges and Universities Global Learning in College: Asking Big questions, Engaging Urgent Challenges October 3‐5, 3013 Make Room for the Local Arlene Walker‐Andrews and Cody Dems Part I—Introduction, A. Walker‐Andrews “Water is prominent on the list of global crises that are predicted to present major challenges to human populations at scales ranging from local to global. Water‐related human morbidity and mortality, which results from widely divergent levels of both water quality and quantity, is already widespread, and almost 80% of the global population faces exposure to high threat levels of water insecurity.” (N. Uchtmann, Global‐e) In a few minutes, I will introduce to you Cody Dems, an undergraduate at the University of Montana. He is acutely aware of this challenge, the scarcity of safe water, and he is participating in a program at UM that allows him to address such a critical, global issue locally. The program at UM is the Global Leadership Initiative, which builds on an awareness that we must prepare today’s students for such global challenges. This program is founded on that premise, along with a couple of NOTs. But first a few questions geared toward audience participation. Please shout out YES or NO in response: Have you traveled internationally? Was Study Abroad part of your college experience? If so, did it transform the way you look at the world? By itself? And last, are the majority of your students able to study internationally? (We can think of many reasons they cannot.) Definitely international travel and study are opportunities we want our students our children, ourselves to have, but we are talking today about global problems like disparate water resources and how to prepare students to address them. Which brings me to my series of NOTs. Global is NOT equivalent to international studies; it is NOT the same as study abroad; it is NOT acquiring a second language. These are all worthy and important goals that may contribute to an appreciation of global issues, but they do not capture the full meaning of global, nor do they by themselves ensure global learning. At UM, our definition of global is more intricate. (I’ve heard similar distinctions made at this conference yesterday and today.) Global problems are those faced by all of us. They are complex, poorly defined, loosely structured challenges common to all people; indeed many affect all life on this planet. We must prepare tomorrow’s citizens, our students, for a life of unprecedented pace and volatility, given them skills to address and solve global problems and communicate across borders and across cultures. These daunting tasks require knowledge, appreciation of differences, interdisciplinary perspectives, collaborative skills, and leadership. At UM we have started, still in its pilot stage, the Global Leadership Initiative to help our students attain these skills, as well as the knowledge and dispositions to solve global issues. Although local solutions to global issues such as climate change are given lip service, undergraduate programs for global learning more often emphasize study abroad or other international experiences. In short, the GLI, for short, allows students to focus on global problems at the local level, often a more viable approach. Through a 4‐year course of scheduled activities, the GLI promotes global mind sets and knowledge through carefully constructed experiences that provide hands‐on learning and community interaction. Cody will talk mostly of the requirement for beyond‐the‐classroom experiences in the 3rd year: How he is taking advantage of a local opportunity to devise solutions to a global problem. The GLI exploits a number of high impact practices. Students are introduced to global questions in the first semester. They enroll in freshman seminars that focus on big problems: Human Rights, Discrimination, Sustainability, the Environment, World Health, the relationship between Mind and Body. Faculty are required to infuse an interdisciplinary approach in these seminars, often team taught. Students must select lectures offered across campus as well, using their big question to select specific talks. In 2013, they’ve had the opportunity to meet author Tracy Kidder, retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, and Steve Lippman (Sustainability Coordinator at Microsoft). As sophomores, students participate in workshops, retreats, and otherwise interact with their peers and invited guests in a Models of Leadership program. Leaders from all areas (nonprofits, government agencies, business, education, the fine arts) come to campus (unpaid) to share their stories with small groups of students. Leadership training is offered at the retreats and in special sessions. In the third year, students jump right in. They take on internships, conduct field studies, participate in more service learning, delve into research, and (yes, where appropriate) study internationally. They apply for funding (contributed to the program by private donors), and must show how the experience will fit their big question. Students get hands‐on experience while focused on global issues, those shared, complex, messy problems. Poverty, health, environment, sustainability, diversity, are all local global issues that are especially amenable for study in Montana. At UM, we take advantage of our local environment to give students unique access to the study of global issues. For example, in Montana, we have ready access to “place.” We see firsthand the effects of climate change, scarcity of water, and species endangerment. Montana is also the setting for seven Native American reservations that provide a window on discrimination, poverty, and other cultural issues. As seniors, students work together in multidisciplinary teams to address a big question. They have been interacting in the classroom but also on discussion boards and in their self‐organized student club, book club, service days, and social events. I am emphasizing local engagement as a way to learn about global issues, but sometimes our students start in an international context and return to the local. For example, Bridgette, one of our GLI students, is keenly interested in sustainability. She is going to Denmark to study cohousing projects and bringing back knowledge to work with her peers on a local project upon her return. (We pay for a passport for all eligible students without one.) The opportunity to address critical issues locally is invaluable. Students can see first‐hand how the community is connected to global trends and how personal experiences are connected to universal ones. This program is open to all students at UM, 200 each year. That is, it is open by lottery to any freshman volunteer. It is not limited to Honors College students or some particular majors or only affluent students. The donor‐funded program provides a tangible, practical context for education, interdisciplinary perspectives, application outside the boundaries of the university, and the opportunity to make a contribution while still a student. Now, I’d like to introduce my co‐author, Cody Dems. When I was submitting this talk, I asked Cody about his decision to study locally and decided no one else could provide such eloquent support for the thesis. Part II—Experiential Learning, Cody Dems How can I work towards solutions to global problems if I do not understand the challenges and successes of the community in which I live? Local learning can give context to international issues. Global problems persist in the United States, Montana, and the Swan Valley, my current home and classroom. I am presently at the mid‐point of my two month long, intensive field studies course offered by Northwest Connections, a nonprofit organization focused on community conservation and education. Northwest Connections engages students in real‐world conflicts through hands‐on field work. We are learning the importance of closely studying the natural land in order to apply the most beneficial management techniques and land use practices. I am only beginning to understand the complexities of over‐arching global issues; however I strongly believe that good communication and a deep understanding of place can be valuable lessons taught at the local level and applied to global problems. Communication is universal. The skills required to communicate and collaborate with a diverse group of people can be practiced at both the local and global scale. While local learning may not provide the novelty of travel to another country, I believe the values learned through community interaction and precise communication can be catalysts for growth. At Northwest Connections we engage ourselves in listening to the diverse views of local residents in order to establish respectful relationships with the people upon whose land we have come. The night before the first frost, we as students harvested the vegetables from the local garden and prepared dinner for over 30 of the 521 local community members. This was an opportunity for us to communicate with neighbors in order to better understand their way of life, relate to their challenges and find beauty in their survival. The skill of communicating with people of different beliefs, up‐bringing, and cultural values is imperative for understanding pressing issues and can be explored at the local level. Solutions to global issues require interdisciplinary, collaborative approaches. Scott Eggman, a US Fish and Wildlife employee, told us that finding solutions “requires that you wear a lot of hats.” Successful problem solving requires strong communication. The ability to attentively listen to the concerns and criticisms of the community in which a problem is based allows us as individuals to build a more informed pathway towards solutions. I believe that successful problem solving must occur with the community as its base. I believe that global solutions should include a great aspect of listening to and respecting the community in which a problem persists. Matt Boyer, a wildlife biologist for the State of Montana who is actively involved in resource management, told us as students that “if you do not get the public in on the ground floor, you are wasting your time. Do not ignore your biggest opponents, engage them.” Place based education provides students with valuable interpretation skills, enabling students to explore the dynamic communities in which they exist. Global does not solely mean international. Global problems are complex and over‐arching. I believe that by acknowledging the intrinsic values of one’s place, we will be able to more closely associate ourselves with the land and the people. We will become more physically, emotionally, and mentally dedicated to finding solutions to complex issues. I think that it is ignorant to wholeheartedly trust classroom education as a means of finding the best solutions. Global leadership requires investing in a community and respecting values other than one’s own. Northwest Connections is teaching me the value of greatly exploring place through deep consideration of the land and the people. In the west we commonly hear the phrase, “water is the new gold.” Time and time again these words are uttered and often times we do not explore the greater issue. As a student at Northwest Connections I am learning in real time the importance of studying our valued resources. How will we manage our freshwater and the ecosystems that are vital to water health? Located between two federally designated wilderness areas, acres of timber forests, and frequently threatened by wildfires, the Swan Valley is a place of indescribable beauty; a valley with steep mountain walls and unmatched aquatic ecosystems. As students we have waded through streams, rivers, and wetlands to better understand water movement and filtration. We have discussed, debated, and contemplated federal practices to poison lakes in an attempt to rejuvenate native fish species. And we have communicated with local loggers, anglers, and managers to broaden our understanding of pressing issues. I believe that place based education has provided me with essential skills that I will be able to apply to pressing global issues. I believe that I am better equipped to tackle water issues around the world, from Africa to South America, and even within the United States. I believe I am more prepared to listen to the people and understand the resources wherever I travel. Solutions will be found when one dedicates themselves to the place in which a problem exists. While I am focusing my studies on topics that are hot issues in the rural community of Condon, deep knowledge of the communication and collaboration associated with each can lead to the application of individualized solutions to global dilemmas. To conclude, I am here today to share with you the value of local learning as a means of tackling complex global issues. Local opportunities can teach skills in communication, collaboration, and application to be used on an international scale. Local learning can be a means of strengthening communities and providing knowledge to students regarding the place in which they live. I hope that you will encourage your students, peers, and friends to explore local markets, businesses, and field opportunities as a way of broadening all of our perspectives on the global world.