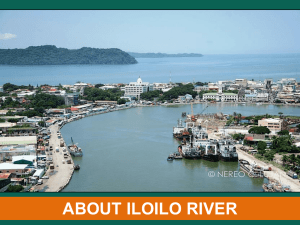

“Ilongo” is derived from the Filipino-Hispanized form of irong

advertisement