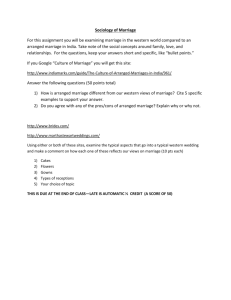

Dearly Beloved A Tool-Kit for the Study of Marriage

advertisement