Common-Sense Construction of Consumer Protection Acts

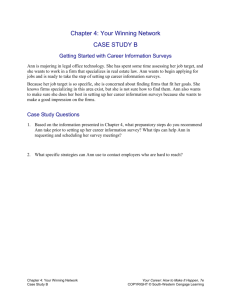

advertisement