TCNS PPP

advertisement

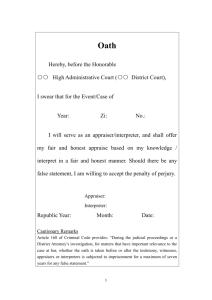

Cultural Competence in Using and Assessing for an Interpreter: A Best Practice Implementation Project Janice Davidson, DNP Student Doctor of Nursing Practice Program Chamberlain College of Nursing This program has been developed solely for the purposes of describing nurse practitioner (NP) provider knowledge, skills, and practice compliance specific to cultural competence in using and assessing for an interpreter, before and after participation in an online multi-modal quality improvement project. The program is posted as a part of this project’s educational intervention and is intended only for such use. The study has been approved for this purpose by the Chamberlain College of Nursing Institutional Review Board. You may download copies of the interventions contained within or contact the author jdavidson@chamberlain.edu to obtain a hard-copy of the interventional resources. Project Background • Best practice evidence indicates that using and assessing for an interpreter to improve patient outcomes is recommended across all healthcare settings (Gray, Hilder, & Donaldson, 2011; Giese, Uyar, Uslucan, Becker, & Henning, 2013). However, evidence reveals that many providers lack the necessary cultural competence skills and resources necessary to support using and assessing for an interpreter (Okrainec, Miller, Holcroft, Boivin, & Greenaway, 2014; Lie, Bereknyei, Braddock, Encinas, Ahearn, & Boker, 2009). Project Objectives • To determine current compliance with evidencebased Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) audit criteria specific to using and assessing for an interpreter. • To improve knowledge regarding best practices specific to cultural competence in using and assessing for an interpreter. • To improve compliance with evidence-based JBI audit criteria specific to using and assessing for an interpreter. • To improve practice outcomes regarding cultural competence in using and assessing for an interpreter. JBI Audit Criteria for Using and Assessing for an Interpreter 1. Accredited interpreters are utilised to obtain informed consent for treatment (medical, surgical, pharmaceutical, therapy, etc.). 2. Individuals are assessed for communication or cultural barriers. 3. Interpreters are utilised for persons with limited English proficiency in accordance with local organisational policy (i.e. interpreter protocols). 4. Standardized methods for identifying individuals with limited English proficiency exist. 5. Verbal or written consent is obtained and documented in the medical record when using an interpreter. Need for Cultural Competence to Inform Using and Assessing for an Interpreter • Attributes for cultural competence • Family assessment skills • Cultural heritage assessment skills • Cultural diversity awareness • Cultural diversity knowledge • Cultural sensitivity • Transcultural caring integrative abilities Understanding Acculturation • Gradual changes produced in one culture through influence of another Understanding Assimilation • Absorption of one culture by another, leading to extinct behaviors The next slide is provided as an interventional resource for those providers interested in downloading a brochure that organizational representatives and providers can use to establish interpreter protocols and methods to access and establish interpreters using verbal or written consent. You may download copies of the interventions contained within or contact the author jdavidson@chamberlain.edu to obtain further evidence in support of the interventional resources. • Protocol for using and assessing for an interpreter (Towers & Harfield, 2013; Jayasekara, 2014). • The brochure at right can be downloaded so organizational representatives and providers can establish the protocol in situ. Family assessment instruments in advanced practice nursing • Overview of FAMTOOL – A Family Health Assessment Tool • Overview of FAMCHAT – A Family Cultural Heritage Assessment Tool • History and Development • Design • Psychometrics The next slide is provided as an interventional resource for those providers interested in downloading a copy of two assessment tools – one to assess culturally-diverse families (FAMTOOL) and the other to assess cultural heritage of individuals within the family (FAMCHAT). You may download copies of the interventions contained within or contact the author jdavidson@chamberlain.edu to obtain further psychometric data and/or a hard-copy of the interventional resources. Companion Tool Development History of FAMCHAT Validation and Psychometrics • • • • • Tertiary validation with elderly Mennonite immigrants from the Ukraine (Davidson, 1994) Secondary validation with Mennonite family members (ages 8-80) from Kansas (Davidson, Regier, & Boos, 2001) Primary validation in village-based nurse practitioner practice in Haiti indicating tool and knowledgebase convergence of international FNP cultural competence (Davidson & DeJong, 2002) Secondary validation with hospitalized patients in Canada (Higginbottom et al., 2012; Higginbottom et al., 2011) Further model explication (Davidson, 20122015) An additional resource that will be made available to participants upon request at the end of the project is a “Getting Research into Practice” (GRiP) report. The GRiP report will offer the results of the clinical audit, selected strategies for improving compliance, and documentation of barriers and required resources to encourage sustainable engagement of stakeholders. If interested, please contact the author jdavidson@chamberlain.edu to obtain a hardcopy of the results of the project and GRiP report. Summary of Interventional Resources 1. 2. 3. 4. Educational intervention designed to increase knowledge about the need for cultural competence to inform using and assessing for an interpreter. Downloadable tool that stakeholders organizational representatives and providers can use to assess for communication or cultural barriers. Downloadable brochure that organizational representatives and providers can use to establish interpreter protocols and methods to access and establish interpreters using verbal or written consent. Getting Research into Practice (GRiP) report for dissemination of audit results, selected strategies for improving compliance, and documentation of barriers and required resources to encourage sustainable engagement. References - continued • • • • • • • Davidson, J. U. (2012). Patient-centered care using clinically-validated instrumentation. FAANP Forum, 3(1), 12. Davidson, J. U. (1994). Portraits of Mennonite health: Selected stories from historical nursing research. Mennonite Life, 49(1), 19-27. Davidson, J. U. (1988). Health embodiment: The relationship between self-care agency and health promoting behaviors. Dissertation Abstracts International, 49(08B). University of Michigan, MI. Davidson, J. U. (1984). Historical perspective of self-care agency among elderly Mennonites at the turn of the twentieth century. Masters Abstracts International. University of Michigan, MI. Davidson, J. U., Regier, T., & Boos, S. (2001). Assessing family cultural heritage in Kansas: Research and development of the FAMCHAT companion tool for family health assessment. The Kansas Nurse, 76(10), 5-7. Giese, A., Uyar, M., Uslucan, H. H., Becker, S., & Henning, B. F. (2013). How do hospitalised patients with Turkish migration background estimate their language skills and their comprehension of medical information - a prospective cross-sectional study and comparison to native patients in Germany to assess the language barrier and the need for translation. BMC Health Services Research, 13196. Gray, B., Hilder, J., & Donaldson, H. (2011). Why do we not use trained interpreters for all patients with limited English proficiency? Is there a place for using family members? Australian Journal of Primary Health, 17(3), 240-249. References - continued • • • • • • • • Higginbottom, G. M. A., Richter, M. S., Young, S., Ortiz, L. M., Callender, S. D., Forgeron, J. I., & Boyce, M. L. (2012). Evaluating the utility of the FamCHAT ethnocultural nursing assessment tool at a Canadian tertiary care hospital: A pilot study with recommendations for hospital management. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 2(2), 1-17. Higginbottom, G. M. A., Richter, M. S., Mogale, R. S., Ortiz, L., Young, S., & Mollel, O. (2011). Identification of nursing assessment models/tools validated in clinical practice for use with diverse ethnocultural groups: An integrative review of the literature. BMC Nursing, 10(1), 16-26. Jayasekara, R. (2014). Interpreter services: Clinician information. Adelaide, Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute. Lie, D., Bereknyei, S., Braddock, C., Encinas, J., Ahearn, S., & Boker, J. R. (2009). Assessing medical students' skills in working with interpreters during patient encounters: A validation study of the Interpreter Scale. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84(5), 643-650. Okrainec, K., Miller, M., Holcroft, C., Boivin, J., & Greenaway, C. (2014). Assessing the need for a medical interpreter: Are all questions created equal? Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health, 16(4), 756760. Towers, K., & Harfield, S. (2013). Interpreter services: Using and assessing for an interpreter. Adelaide, Australia: Joanna Briggs Institute. Weeks, S. K., & O’Connor, P. C. (1997). The FAMTOOL family health assessment tool. Rehabilitation Nursing, 22(4), 188-191. Weeks, S. K., & O’Connor, P. C. (1994). Concept analysis of family + health = a new definition of family health. Rehabilitation Nursing, 19(4), 207-210. Acknowledgements • • University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Centre for Evidence-Based Patient and Family Care: An Affiliate of the Joanna Briggs Institute Chamberlain College of Nursing: • Dr. Valda Upenieks, Advisor • Dr. Sue Fletcher, Preceptor • Dr. Pat Fedorka, Mentor • Dr. Ellen Poole, Coach