Full Journal - Mount Vernon Nazarene University

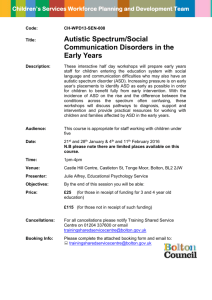

advertisement