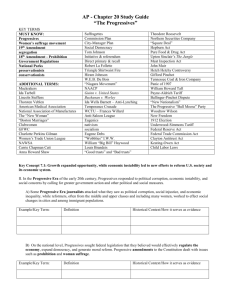

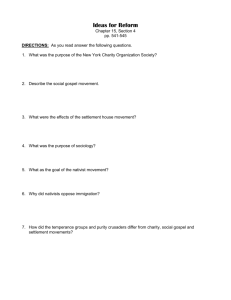

1 Unit Title: The Progressive Movement

advertisement