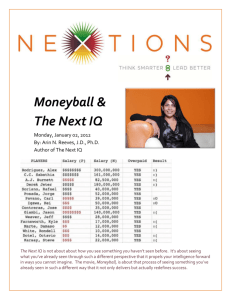

Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game

advertisement