A “Principled” Approach to Coverage? The American Law Institute

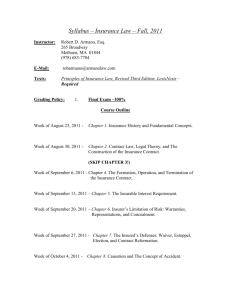

advertisement