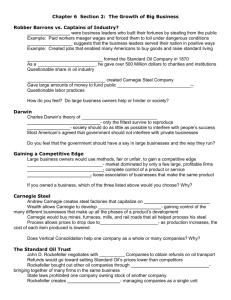

Chapter 18 The Rise of Industry 1860-1900

advertisement

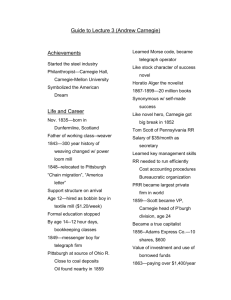

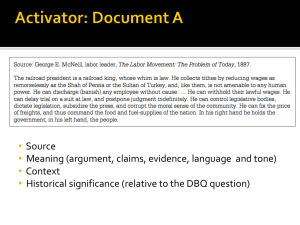

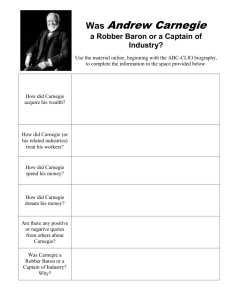

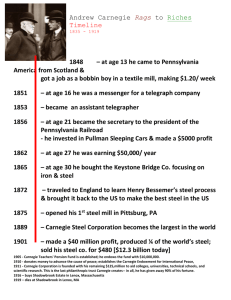

Chapter 18 The Rise of Industry 1860-1900 Between 1865 and 1890, the United States catapulted into the position of the world's greatest industrial power. How were men like John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie able to transform America into an industrial giant? What were the benefits and costs for the nation as a whole? CHAPTER SUMMARY In 1848, the 13-year-old son of a Scottish immigrant named Andrew Carnegie worked as a bobbin boy in a Pittsburgh textile mill for 20 cents a day. By 1900, Carnegie was the richest man in America. As head of Carnegie Steel he enjoyed an annual income of $40 million. His company produced more steel than all of Great Britain, supplying steel for the Brooklyn Bridge and the Washington Monument. In 1901 he sold his company to financier J. P. Morgan for $500 million and retired to a castle in Scotland. (Morgan merged Carnegie Steel with other steel mills to form United States Steel, capitalized at $1.4 billion.) Carnegie is the classic example of the "rags to riches" tale, and certainly one of the most productive, successful, and civic-minded of the so-called "robber barons" of the American industrial era. The keys to Carnegie's success reveal much about the business environment in which he thrived. Unlike many of the industrial leaders of the era (such as George Westinghouse), Carnegie was not an inventor or technical expert. He was a shrewd businessman. He took advantage of the boom-and-bust business cycle, jumping in during hard times, building and buying when prices were low. He hired skilled managers who drove his workers hard. (Between 1870 and 1910 there were almost 4,000 injuries or deaths at Carnegie's South Works alone.) He ran his steel mills "24X7" year-round, closing only on July 4th. Carnegie scrapped machinery and workers to keep costs down and undersell competitors. His steel empire spread both horizontally, by purchasing rival steel mills and constructing new ones, and vertically, buying up sources of supply and transportation. In short, he knew how to compete. Carnegie is especially interesting as a historical case study because he not only personified the philosophy of Social Darwinism, he also wrote about it in The Gospel of Wealth (1889): "We accept and welcome... great inequality of environment; the concentration of business, industrial and commercial, in the hands of a few; and the law of competition between these as being not only beneficial, but essential to the future of the race." Indeed, the laissez faire political/ economic climate of the era gave wise and ambitious entrepreneurs like Carnegie a free hand. The fact that most people failed to follow in Carnegie's footsteps was frequently attributed to laziness, ignorance, and moral deficiencies. To his credit, Carnegie left most of his fortune to libraries, colleges, and the Carnegie Foundation for Peace. "The kept dollar is a stinking fish," he wrote. "The man who dies rich, dies disgraced." Men like Carnegie certainly helped increase national wealth as America became the leading industrial power in the world. Yet they also concentrated power, corrupted politics, and made the gap between rich and poor more apparent than ever. In 1890, the richest 9 percent of Americans held nearly three-quarters of all wealth in the United States. But by 1900, one American in eight (nearly 10 million people) lived below the poverty line. An unskilled worker could expect about $1.50 for a 10-hour day. It took about $600 to make ends meet, but most manufacturing workers made under $500 a year. Native-born white Americans tended to earn more than immigrants, those who spoke English more than those who did not, men more than women, and all others more than Blacks, Latinos, and Asians. A great many children worked in American factories, 1 but few repeated the rags-to-riches rise of Andrew Carnegie. Child labour was a widespread practice encouraged by industry, agreed to by parents, and ignored by government. By 1890, the industrial labour force included some 1.5 million children. For employers, the tiny workers were a bargain, and besides, they claimed that factory work was "good for the little devils." On average, children worked 60 hours a week and carried home pay checks a third the size of adults. "If you speak, they say, 'Get out.'" Moreover, the practices of big business subjected the economy to enormous disruptions. The banking system could not keep up with the demand for capital, and businesses failed to distribute enough profits to sustain the purchasing power of workers (let alone provide a safe and healthy working environment or a comfortable standard of living). Altogether, three severe depressions rocked the economy between 1873 and 1897. With hard times came fierce competition as the industrial barons ruthlessly cut costs. With the growing instability of the economy and its adverse impact on workers, early labour unions became increasingly active [see Lecture 4]. The financial "panic" [depression] of 1893 was especially disconcerting to business, labour, and government officials, but striking workers were generally afforded little public sympathy. Mostly they felt the heavy boot of strike-breakers. Employers sometimes hired "detectives" from the Pinkerton agency--uniformed thugs--and also sought relief through the courts. Because state and federal lawmakers feared unions and did little if anything to protect the rights of organized labour, judges usually sided with business, issued injunctions to end strikes, acquiesced in the use of federal troops as strike-breakers, and sent union leaders to prison. Still, many American workers, seeing some improvement in their lives, believed in the American dream. This largely explains why the socialist movement never caught on despite the great inequality of wealth, harsh working conditions, and periods of labour unrest and radical protest. The new industrial order reshaped America in countless beneficial ways, but the costs were high. The power of business to exploit workers and befoul the environment grew with very little government interference. It should be noted that to the extent that government aided the rise of men like Carnegie--by investment, railroad land grants, tariffs, pro-business laws and court rulings--laissez faire capitalism never truly existed. And in time, led by Progressives like Theodore Roosevelt, the federal government began to exercise not just a helping hand but a guiding hand, balancing the interests of business, labour, consumers, and the environment. Approximate Date and Event 1870 John D. Rockefeller incorporates Standard Oil Company of Ohio 1873 Carnegie Steel Company founded; Panic of 1873 brings on a six-year depression 1876 Thomas Edison establishes "invention factory" at Menlo Park, New Jersey; Rutherford B. Hayes chosen president in controversial election 1877 Great Railroad Strike - first major interstate labour strike 1882 Rockefeller's Standard Oil becomes the nation's first trust 2 1885 Bell organizes the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) 1886 George Westinghouse develops electric motor using alternating-current (AC) system; American Federation of Labour organized; Haymarket Square riot/bombing in Chicago 1888 Edison General Electric Company formed 1889 The Gospel of Wealth published by Andrew Carnegie (Social Darwinism) 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act passed - used against organized labour, not business 1892 Homestead Steel strike 1893 Panic of 1893 marks beginning of a three-year depression 1894 Pullman strike crushed by federal troops - railway union president Eugene Debs imprisoned. 1901 J. P. Morgan incorporates United States Steel as the first billion-dollar company; Eugene Debs founds the Socialist Party of America; William McKinley assassinated and Theodore Roosevelt becomes president 3