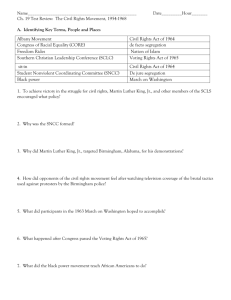

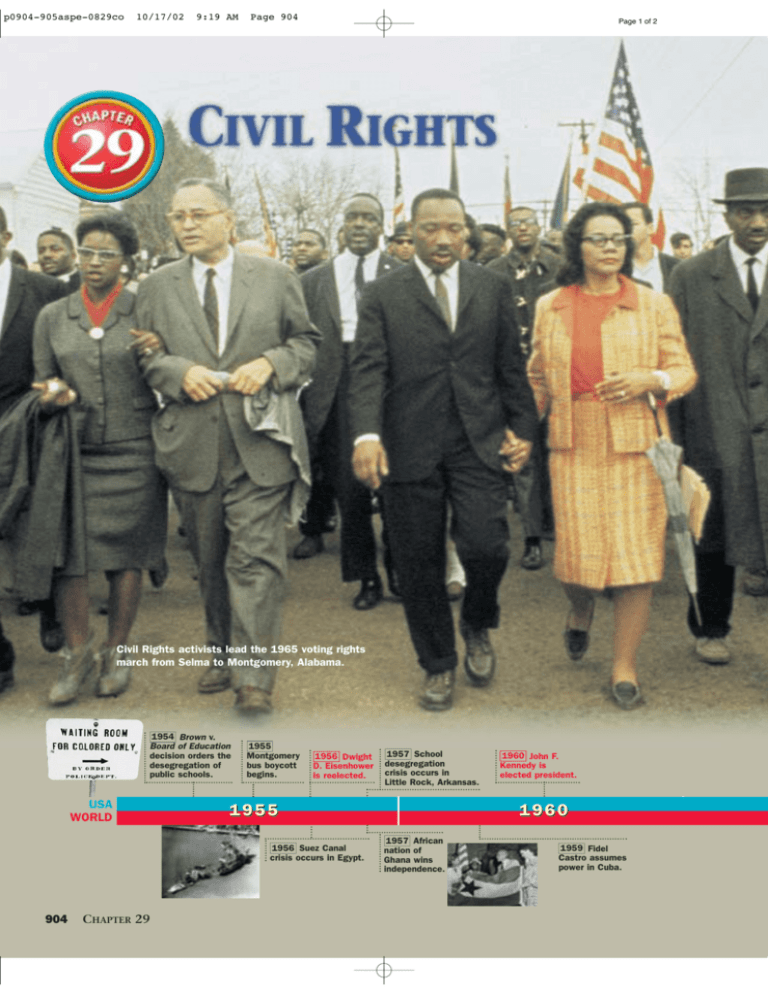

Chapter 29 pages 904-933 - Community Unit School District 200

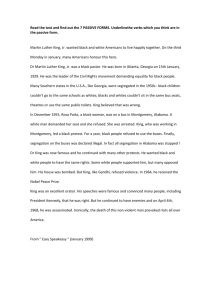

advertisement