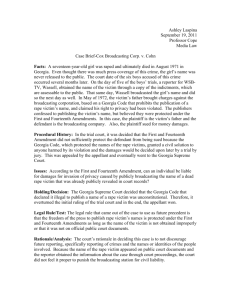

NOTES The Media's First Amendment Rights and the Rape Victim's

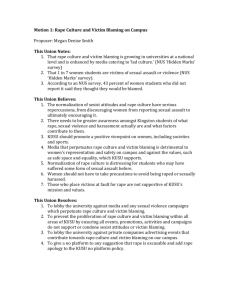

advertisement