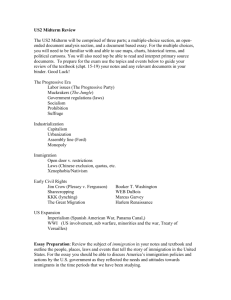

September/October 2013 Immigration Law The Proclamation of 1763

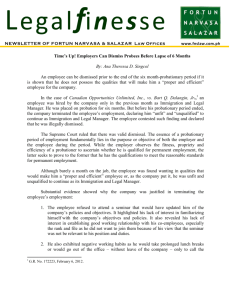

advertisement