Economic Impacts of the Regional Greenhouse

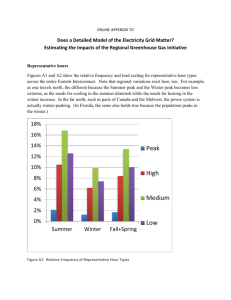

advertisement