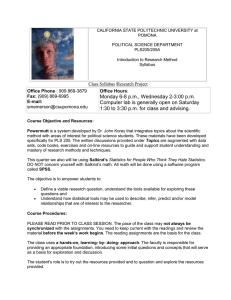

syllabus - Department of Political Science

advertisement

Introduction to Research in Political Science Political Science 104 Winter 2012 Heather Stoll hstoll(at)polsci.ucsb.edu 3715 Ellison Hall Office Hours: TH 12:30–3:30 p.m. or by appointment Class Meeting Time: T TH 11:00 a.m.–12:15 p.m. Class Meeting Place: CHEM 1171 Class Website: http://www.polsci.ucsb.edu/faculty/hstoll/classes/polisci104 1 Course Objectives This course is an introduction to research in political science. Its goal is to familiarize you with the social scientific study of politics. We will learn how to take a scientific approach to questions about political phenomena instead of the more familiar advocacy approach taken by politicians, interest groups, and lobbyists. In other words, we will learn how to ask empirical questions about the political world; how to answer these questions scientifically using the appropriate types of evidence; and how to clearly convey our arguments, evidence, and conclusions to others. The course topics will accordingly include the logic of the scientific method; the measurement of political concepts; research design and methods of data collection; statistical and graphical techniques for describing data; and the principles of statistical inference. Particular attention will be paid to methods for analyzing quantitative data because this is the most widely used methodology in political science today. You will also learn SPSS, a user-friendly statistical software program. At the end of the course, we hope that you will be comfortable reading and critiquing arguments about real world political problems. Learning to think social scientifically in this manner is a skill that you will find useful in your future upper division political science courses. It will also be beneficial beyond the walls of UCSB: in a career in the policy, government, journalistic, business, or legal professions, as well as in every-day life as a citizen of a democracy. No background in statistics or mathematics beyond high school algebra is assumed. The major prerequisite is a commitment to learning how to do political science. 2 Course and Contact Information The syllabus, assignments, paper guidelines, study guides, links to assigned readings that are available electronically, and other handouts are all available from the course website. Announcements will also be posted to the website; it should be your first port of call if you’re unsure about what’s happening when and where. You have two ways to contact me: • Office Hours: I encourage you to stop by early in the quarter so that you can get to know me, and vice versa. Don’t, in other words, feel shy about coming to office hours. A face-to-face conversation is often the best way to discuss any non-trivial questions. 1 • E-mail: I will generally respond within twenty-four hours to e-mails that I receive Mondays through Fridays. Often my response will come in far less than twenty-four hours, but I do not guarantee it. Note that I rarely check e-mail in the evenings. E-mails that I receive over the weekend will be answered on Monday. I will notify you of any planned deviations from this pledge, such as occasions when I am out of town and hence away from my e-mail. I will also usually arrive ten minutes early to class, so you can catch me then. The TAs for the course are Tabitha Benney (tbenney(at)umail.ucsb.edu; TH 1:00, 2:00 and 3:00 sections); Anne Pluta (acpluta(at)umail.ucsb.edu; F sections); and Marcus Arrajj (arrajj(at)umail.ucsb.edu; TH 4:00 section). Information about their office hours will be posted on the course website. 3 Initial Attendance and Waitlist Information regarding the waitlist will be given out at the first lecture, so those who would like to crash should attend. If you decide not to take the class, please drop as soon as possible to make room for others on the waitlist. Students who do not attend the first section may be dropped from the course. 4 Course Requirements This is a five-unit class with both lecture and lab components. It does not require as much reading as many political science courses, but mastering the concepts requires you to more actively engage the material than you may be accustomed to doing. Several old adages (such as ‘practice makes perfect’ and ‘you only learn by doing’) apply. Accordingly, we will ask you to regularly reflect upon the material in written assignments as well as through participation in both lectures and discussion sections. The course requirements and the weight of each towards your course grade are as follows: • A research paper on a topic of your choice. Your goal in writing the paper is to apply the skills that you have learned in the class. That is, you will conduct an empirical analysis of a political science research question and seek to transmit the results of your research using clear, jargon-free prose and compelling visual aids. We think that you will ultimately find this process to be a rewarding experience. To aid you, both to ensure that you do not attempt to write the whole paper in one night at the end of the quarter and to nip any serious problems in the bud, so to speak, components of the paper will be assigned as homework. The final paper should be between 10 and 15 pages, double spaced, with standard font and margins. It is due at 4:00 p.m. on Friday, 16 March (the last day of classes). Note that no late papers will be accepted except in cases of documented medical or family emergencies. (25%) • Five (approximately bi-weekly) homework assignments to be announced in class and posted to the website. You will always have at least one week to complete the assignments. (15%) • An in-class midterm examination. Tentative date: 14 February. (20%) • An in-class final examination. The final examination is scheduled for Wednesday, 21 March from 12:00–3:00 p.m. (30%) 2 • Participation in lab/discussion section. Attendance of sections, which meet once a week, is required, as is active participation in the section’s discussions and activities. While I will from time to time present computer output in class, sections are the place where you will learn the computer software that implements the methods we discuss. Additionally, they serve as a venue for you to discuss the material covered in the lectures and texts. Sections will begin meeting in the first week of the quarter in their regularly scheduled rooms. In subsequent weeks, sections will meet in the assigned computer lab, SSMS 1304. (10%) • Participation in lecture. While attendance of lectures is not required, material that is not in the readings will often be presented. If you choose to be somewhere else during lecture, that is your decision, but you are responsible for the material covered. However, if your absence is due to either illness or a family emergency, I will help you to make it up. Even though you will not be formally graded on participation in lecture, coming to class prepared (i.e., having done the assigned readings prior to class) and actively participating in discussions will enable you to get the most out of the class. (0%) 5 Grading Homework assignments will be graded according to the following four category scale: “check plus,” exceeds expectations; “check,” satisfies expectations; “check minus,” falls short of expectations but is minimally satisfactory; and ‘F’, either not acceptable or not received. We will then translate these scores into letter grades at the end of the quarter. You will receive letter grades for the exams and research paper up front. 6 Submitting Assignments If your TA is Marcus, all written assignments—both your homework assignments and research paper—should be submitted as paper copies to his political science mailbox. If your TA is either Tabitha or Anne, written assignments should be submitted electronically to them at the e-mail addresess given above. The late policy for written assignments is designed to avoid punishing students whose work is handed in on time. • Homework assignments: Since we know that sometimes life gets crazy, you begin the quarter with two free “late days” (a twenty-four hour period that includes weekends and holidays). Just let your TA know if you’d like to use a late day when handing an assignment in late. After you have used up your late days, homework assignments will be penalized one category (e.g., from a “check plus” to a “check”) for up to a twenty-four hour period late, after which you will receive an ‘F’ for the assignment. However, late penalties will not drop the score below minimal passing (a “check minus”). Advance arrangements to hand in homework assignments late may made be on an individual basis with your TA at least twenty-four hours in advance of the official due date and time. • Research paper: no late research papers will be accepted. Exceptions to this policy will of course be made for documented cases of medical or family emergencies. Note that you may always hand in written assignments early. 3 7 Plagiarism UCSB defines plagiarism as “the use of another’s idea or words without proper attribution or credit” (see “Academic Integrity at UCSB: A Student’s Guide”, available at http://judicialaffairs. sa.ucsb.edu/PDF/academicintegflyer.pdf). It is a serious academic offense. For this course, while you may discuss assignments and your final paper with fellow students, the write-ups must be your own. This means that you can talk through an assignment with someone else, but you must then on your own (in another room, later in the day, in silence) put the answer to the questions down on paper in your own words. Plagiarism and other types of academic dishonesty will be reported to the Student Judicial Affairs Office for disciplinary action and will result in an automatic fail. If you are not sure what constitutes plagiarism, ask either me or your TA! Also ask us for help if you’re struggling before you resort to such desperate measures. 8 Required Reading Materials The following books are required for the course. They are available for purchase from the bookstore or from various internet sources such as Amazon.com: • Salkind, Neil. 2011. Statistics for People Who (Think They) Hate Statistics. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. • Shively, W. Phillips. 2011. The Craft of Political Research. 8th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. For those looking to save money, you may purchase used copies of older editions of these texts. For those really looking to save money, older editions (the 2nd and 3rd) of the Salkind and both the current and an older edition (the 6th) of the Shively are available from the library’s Reserve Book Service; I have provided comparable page numbers for the older editions in brackets and will be happy to help you figure out comparable page numbers for even older editions—just ask. The required reader is available from The Alternative in Isla Vista. I will also make two copies available through the library’s Reserve Book Service. To save trees, some readings are not included in the reader because they are available electronically; links to these readings can be found on the course website. For copyright reasons, one reading is available from the library’s Electronic Reserve Service (http://eres.library.ucsb.edu, using the password supplied in class. On the schedule of required readings below, those that are found in the reader are marked [R]; those that are available on-line from the course website are marked [E]; and those marked [ERES] are available from the Electronic Reserve Service. You are responsible for all of these readings, including the ones not appearing in the reader. 9 Recommended Reading Materials In addition to the books appearing on the syllabus, the following books are good resources to consult if you wish to investigate a course topic further. Agresti, Alan and Barbara Finley. 1997. Statistical Methods for the Social Sciences. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. 4 Booth, Wayne, Joseph M. Williams and Gregory C. Colomb. 2003. The Craft of Research. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Freedman, David, Robert Pisani, and Roger Purves. 1998. Statistics. 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane and Sidney Verba. 1994. Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Paulos, John Allen. 1988. Innumeracy: Mathematical Illiteracy and Its Consequences. New York: Random House. 10 Statistical Software You may download a trial version of SPSS version 20 for Windows, a slightly newer version of the statistical software program that we will use (the computer labs have version 19), from http: //www.spss.com/downloads/. It expires after fourteen days, so this might come in handy towards the end of the quarter when you’d like to work on your paper at home. 5 11 Schedule (All Dates Tentative) Introduction: From Montesquieu to Diamond (10 Jan) Diamond, Jared. 1999. “A Natural Experiment of History.” In Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. Chapter 2, p. 53–66. [R] The Social Scientific Enterprise: Overview and Key Concepts (12 and 17 Jan) Salkind. A Note to the Student, p. xvii–xviii, Chapter 1, p. 1–16, and Chapter 7, p. 136–138 [2nd ed.: p. xvii–xviii, p. 1–16, p. 112–115; 3rd ed.: p. xvii-xviii, p. 1–16, p. 130–132]. Shively. Chapters 1–2, p. 1–31 [6th ed.: same]. Best, Joel. 2001. Damned Lies and Statistics: Untangling Numbers from the Media, Politicians, and Activists. Berkeley: University of California Press. Introduction, p. 1–8, and Chapter 1, p. 9–29. [R] Feynman, Richard. 1992. “Cargo Cult Science.” In Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! Adventures of a Curious Character. London: Vintage. p. 338–346. [R] Crichton, Michael. 2008. “Aliens Cause Global Warming.” Excerpt of speech in The Wall Street Journal, 7 November. [E] Dean, Cornelia. 2006. “When Questions of Science Come to a Courtroom, Truth Has Many Faces.” The New York Times. 5 December. [E] Measurement (19 and 24 Jan) Salkind. Chapter 6, p. 101–107, p. 117–124 [2nd ed.: p. 273–279, p. 289–296; 3rd ed.: p. 97–103, p. 112–118]. Shively. Chapters 3–5, p. 32–73 [6th ed.: same]. Best, Joel. 2001. Damned Lies and Statistics: Untangling Numbers from the Media, Politicians, and Activists. Berkeley: University of California Press. Chapter 2 [in part], p. 30–52 and 59–61. [ERES] Gewirtz, Paul and Chad Golder. 2005. “So Who Are the Activists?” The New York Times. 6 July. [E] Holmes, Steven. 1994. “You’re Smart If You Know What Race You Are.” The New York Times. 23 October. [E] Describing Data: Statistical and Graphical Techniques (26 and 31 Jan, 2 and 7 Feb) Salkind. Chapters 2–5, p. 17–100, and Chapter 16, p. 267–284 [2nd ed.: p. 18–100, p. 242–257; 3rd ed.: p. 17–96, p. 245–261]. Shively. Chapter 8, p. 112–132, and Chapter 9, p. 139–140 [6th ed.: p. 110–130, p. 131–137]. Tufte, Edward. 1997. “Visual and Statistical Thinking: Displays of Evidence for Making Decisions.” In Visual Explanations. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press. Chapter 2 [in part], p. 27–37. [R] Tufte, Edward. 2001. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press. Selected pages: 13–15, 53, 76–77, 107. [R] The Economist. 2005. “Economics of Happiness: Change and Decay.” 25 August. [R] 6 Sampling and Statistical Inference (9, 16, 21 and 23 Feb) Salkind. Chapter 7, p. 127–136, Chapters 8–12, p. 141–220, Chapter 15, p. 253–265, and Chapter 17, p. 285–295 [2nd ed: p. 102–112, p. 118–192, p. 228–241, p. 261–272; 3rd ed.: p. 121–130, p. 134–200, p. 233–244, p. 262–273]. Shively. Chapter 7, p. 97–111, and Chapter 10, p. 150–165 [6th ed.: p. 97–109, p. 147–163]. Best, Joel. 2001. Damned Lies and Statistics: Untangling Numbers from the Media, Politicians, and Activists. Berkeley: University of California Press. Chapter 2 [in part], p. 52–58, and Chapter 3 [in part], p. 70–71. [R] The Economist. 2004. “Economics Focus: Signifying Nothing?” 29 January. [R] The Economist. 2004. “The Iraqi War: Counting the Casualties.” 4 November. [R] Holden, Constance. 2009. “The 2010 Census: America’s Uncounted Millions.” Science 324: 1008-1009. [R] Research Design and Causality (28 Feb, 1, 6 and 7 Mar) Shively. Chapter 6, p. 74–95, and Chapter 9, p. 142–149 [6th ed.: p. 74–95, p. 140–146]. Campbell, Donald T. and H. Laurence Ross. 1968. “The Connecticut Crackdown on Speeding: Time-Series Data in Quasi-Experimental Analysis.” Law and Society Review 3 (1): 33–54. [E] Johnson, Janet Buttolph, Richard A. Joslyn and H. T. Reynolds. 2008. Political Science Research Methods. 6th ed. Washington, D. C.: CQ Press. Chapters 5, p. 122–181, and 10, p. 297–350. [R] Paulos, John Allen. 2001. “Do Concealed Guns Reduce Crime? Economist Says Guns Deter Criminals, But It’s Not That Simple.” ABCNews.com. 1 March. [E] Beyond the Quantitative (Comparative and Case Studies) (13 Mar) Lijphart, Arend. 1971. “Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method.” American Political Science Review 65 (3): 682–93. [E] Mill, John Stuart. 1970. “Two Methods of Comparison.” In Amitai Etzioni and Fredric Dubow, eds. Comparative Perspectives: Theories and Methods. Boston: Little, Brown. [R] Diamond, Jared. 1999. “The Future of Human History as a Science.” In Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. Epilogue [in part], p. 405–420. [R] Review (15 Mar) 7 13. — Effects arising from the Climate of England In a nation so distempered by the climate as to have a dis-relish of everything, nay, even of life, it is plain that the government most suitable to the inhabitants is that in which they cannot lay their uneasiness to any single person’s charge, and in which, being under the direction rather of the laws than of the prince, it is impossible for them to change the government without subverting the laws themselves. And if this nation has likewise derived from the climate a certain impatience of temper, which renders them incapable of bearing the same train of things for any long continuance,1 it is obvious that the government above mentioned is the fittest for them. This impatience of temper is not very considerable of itself; but it may become so when joined with courage. It is quite a different thing from levity, which makes people undertake or drop a project without cause; it borders more upon obstinacy, because it proceeds from so lively a sense of misery that it is not weakened even by the habit of suffering. This temper in a free nation is extremely proper for disconcerting the projects of tyranny, which is always slow and feeble in its commencement, as in the end it is active and lively; which at first only stretches out a hand to assist, and exerts afterwards a multitude of arms to oppress. Slavery is ever preceded by sleep. But a people who find no rest in any situation, who continually explore every part, and feel nothing but pain, can hardly be lulled to sleep. Politics are a smooth file, which cuts gradually, and attains its end by a slow progression. Now the people of whom we have been speaking are incapable of bearing the delays, the details, and the coolness of negotiations: in these they are more unlikely to succeed than any other nation; hence they are apt to lose by treaties what they obtain by arms. From Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, 1748. 1 It may be complicated with the scurvy, which, in some countries especially, renders a man whimsical and unsupportable to himself. See Pirard’s “Voyages,” part II. chap. xxi. 8