recommendations for early childhood assessments

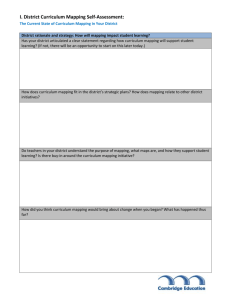

advertisement