Praise for Glamour

‘In her relish for brassy blondes, gutsy flamboyance and tinsel vulgarity,

Dyhouse writes like a woman who knows her way around the lipstick

counter and the flea market. She shows how a parade in the trappings

of glamour expressed aspiration and assertion at odds with mousy,

unobtrusive conformity. Glamour was a cynical business, but also a shriek

of camp defiance. All fur coat and no knickers. Dyhouse has whipped

the stopper from a vintage bottle of Evening in Paris and conjured a

vanished world – cheap, a little tarty, but impossible to forget.’

Amanda Vickery, author of Behind Closed Doors

‘In Glamour: Women, History, Feminism, Carol Dyhouse has written a study

of the conception of glamour in the twentieth century that is sprightly,

provocative, and penetrating. She adds greatly to our understanding

of a phenomenon that has been central to women’s attitudes toward

themselves … This work will be interesting to both scholars and general

readers alike.’

Lois Banner, author of American Beauty

‘In her survey of changing ideas about “glamour” throughout the

twentieth century and beyond, Carol Dyhouse has succeeded in

fashioning scholarly empirical research into a clear, engaging and

enthusiastic account.’

Elizabeth Wilson, author of Adorned in Dreams

‘Rigorously researched and persuasively argued, Glamour represents

an important contribution to the social history of fashion and of

fabulousness.’

Caroline Weber, author of Queen of Fashion

‘Riveting – from perfume to sexual politics and the precise definition of

“It”, Dyhouse gives us an entertaining and innovative analysis of a topic

that, while hitherto underexplored, has a huge impact on all our lives.’

Sarah Gristwood, author of Fabulous Frocks

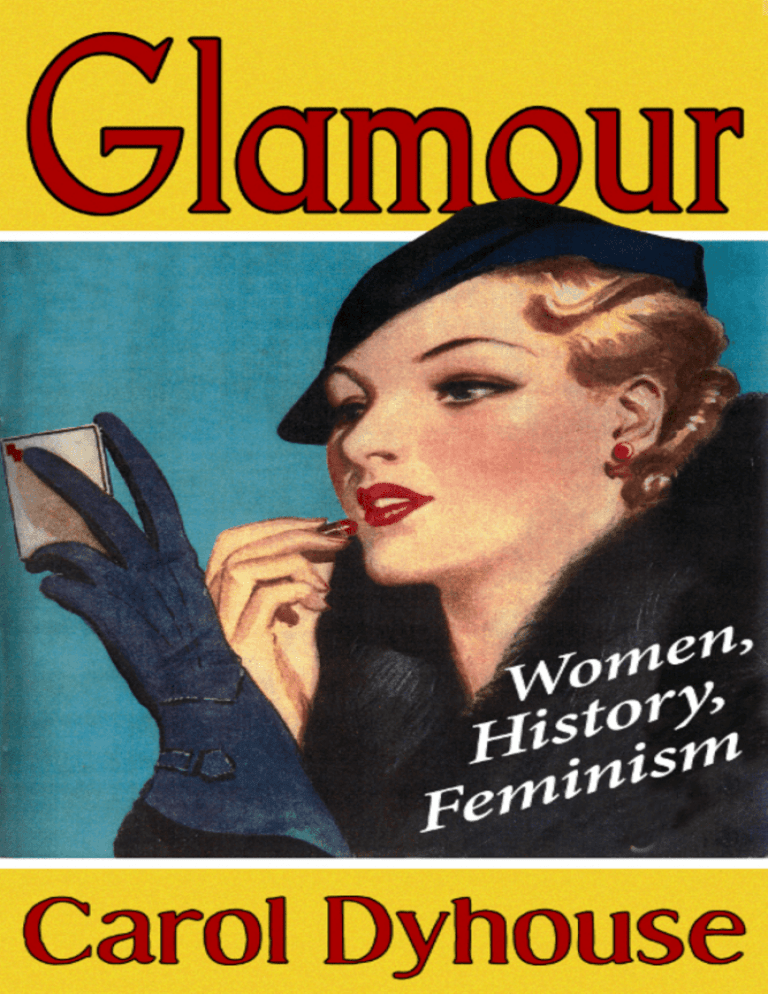

Glamour

Women, History, Feminism

Carol Dyhouse

Zed Books

London & New York

Glamour: Women, History, Feminism was first published in 2010

by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London N1 9JF, UK

and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA

www.zedbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Carol Dyhouse 2010

The right of Carol Dyhouse to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Text and cover designed by Safehouse Creative

Index by John Barker and Nick von Tunzelmann

Printed and bound in Great Britain by the MPG Books Group

Distributed in the USA exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan,

a division of St Martin’s Press, LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York,

NY 10010, USA

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed

Books Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data available

ISBN 978 1 84813 407 2

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

vi

viii

Introduction 1

1

The origins of glamour: demi-monde, modernity, ‘It’

9

2

Hollywood glamour

29

3 Dreams, desires and spending

49

4 Princesses, tarts and cheesecake

81

5

Revolutions

109

6 Glamazons, grunge and bling

133

7 Perspectives and reflections: glamour for all?

151

Notes

Sources and select bibliography

Index

169

203

223

Illustrations

Advertisement for Helena Rubinstein’s Valaze skin creams, 1920s

16

Advertisement for Grossmith’s perfume Phul-Nana, 1920s 18

Perfume card advertising Shem-el-Nessim, 1920s

20

Wana-Ranee, another of Grossmith’s ‘oriental’ perfumes, 1920s

22

Fur wrap edged with rows of tiny feet and tails, 1900s

24

Adverts for Revillon Frères,1920s 26

Gloria Swanson on a tiger-skin

31

Adelaide Hall

34

Marlene Dietrich as Shanghai Lily in Shanghai Express 35

Coats with intricately stitched pelts from the late 1920s

36

Madeleine Carroll looking slinky in bias-cut satin

39

Advert for Ballito silk stockings, mid 1930s

40

Pulp novelette from Gramol Publications, 1935

50

Cover of the first issue of Girls’ Cinema, October 1920

53

Film Fashionland 54

Designs from Film Fashionland, mid 1930s

56

Advertisements from the British Fur Trade, 1937

60

Advert for Snowfire vanishing cream and face powder, mid 1930s

63

Cover of Miss Modern, March 1935 66

Advert for Atkinson’s popular scent Californian Poppy, 1940s

69

Advert for Coty’s Chypre, 1938

71

Illustrations

Wedding photo, wartime Leeds

78

Kestos advert, 1950s

82

Model Cherry Marshall in an advert for Susan Small, 1949

84

Hairdresser Betty Burden, photographed by Bert Hardy 86

Model Barbara Goalen, photographed by John French,1950

94

Lady Docker, 1954

98

Diana Dors on the cover of Picturegoer, December 1955

100

Alma Cogan performs for the BBC Home Service, 1954 103

Joan Collins on the cover of Picture Post, September 1954

106

A mother takes her daughter shopping in the 1950s

111

Adverts for Marchioness velvets (Martin & Savage Ltd)

and Hoggs of Hawick

116

Shirley Bassey at the London Palladium, 1965

127

Claudia Jones with black beauty queen Marlene Walker, 1960

129

Claudia Jones congratulating Carol Joan Crawford 130

Shoulder-padded glamazon in an advert for Krizia,

British Vogue, 1985

137

1980s tailored androgyny in an advert for Georges Rech,

British Vogue, 1985

139

vii

Introduction

When it was first used, in the nineteenth century, the word ‘glamour’

meant something akin to sorcery, or magical charm.1 It became a buzz

word in the twentieth century, its strongest associations being with

American cinema between the 1930s and 1950s, the classic period of the

Hollywood ‘dream factory’, and in particular the screen and still photography of its female stars.

Men as well as women can be described as glamorous, and the term

can also be applied to things, places or lifestyles. Any judgement of what

is and is not glamorous will be partly subjective: glamour (like beauty)

can be judged to exist in the eye of the beholder rather than that which

is beholden. Notions of what constitutes glamour have changed through

time, and yet there are marked continuities. Glamour has almost always

been linked with artifice and with performance, and is generally seen

as constituting a form of sophisticated – and often sexual – allure. This

book will focus on feminine glamour, the relationship between glamour

and fashion, and what glamour has meant to women in modern social

history.

‘Glamour’ as a term implying a form of sophisticated feminine

allure has a history which is interwoven with changing constructions of

femininity, consumerism, popular culture, fashion and celebrity. Few of

Glamour

those who have written on the subject have done so from a position of

neutrality. Some feminist writers have adopted a critical stance towards

what they have seen as the oppressive prescriptions for feminine attractiveness bolstered by capitalism and patriarchy.2 A growing body of social

critics and environmentalists deplore the ravages of unbridled consumption in the developed and developing worlds, highlighting the problems

of affluence and its inability to ensure human contentment and happiness.3 Women occupy uncertain positions in histories and critiques of

consumerism: representations of the prudent and socially aware ‘woman

with the basket’ of the early Co-operative Movement, the make-do-andmend housewife of wartime austerity, changed radically after 1945. In

the oft-quoted words of Mary Grieve, editor of the magazine Woman, in

the 1950s ‘it dawned upon the business men of the country that the Little

Woman was now Big Business’.4 Advertisers began to recognise more fully

the importance of ordinary women as consumers, and as living standards

rose, patterns of consumption expanded and changed. Concern about

the shopping addictions of well-off women was nothing new.5 However,

household expenditure surveys in the early twentieth century showed that

working-class women spent next to nothing on themselves, prioritising

the needs of male breadwinners and children.6 By the end of the century

women’s massively increased spending on fashion and beauty products

had helped to reverse this image of self-sacrifice and to ensure their new

representation as shoe obsessives and shopaholics, duped by the claims

of manufacturers of beauty products and anti-ageing creams. Criticism

of supermodels and celebrities can also foster a kind of misogyny, with

regular media witch-hunts around the rich and brainless – particularly

when glamorous and female.

Amongst the range of different ideals of femininity available to

women over the past century, what did the image of the glamorous woman

signify? Did – and does – it simply imply the objectification of woman,

subject to the male gaze? Did – and does – it represent the seduction

or subjection of women as consumer in capitalist society? John Berger

memorably defined glamour as a form of envy.7 Can ideals of glamour

be blamed for feminine insecurities, body dysmorphia, eating disorders,

addiction to cosmetic surgery, or a refusal to come to terms with old

age? Or did glamour offer a kind of agency to women, even sometimes

a way of getting their own back on patriarchy? If femininity can be seen

2

Introduction

as a form of belittlement, associated with the demure, the dainty and the

unassuming, then glamour – it can be argued – could offer a route to a

more assertive and powerful form of female identity.8 Glamour was often

linked to a dream of transformation, a desire for something out of the

ordinary, a form of aspiration, a fiction of female becoming.

What is fashionable is not always glamorous, and glamour has not

always been fashionable. In twentieth-century fashion, glamour had its

clichés: glitter, fur and slinky dresses, hothouse flowers and a slash of

bright red lips. Glamour was about luxury and excess. It spoke of power,

sexuality and transgression. It could also be about pleasure, the sensuousness of fur, silk and rich fabrics, the heady sensuality and reveries

of perfume. This book will suggest that in many contexts a desire for

glamour represented an audacious refusal to be imprisoned by norms

of class and gender, or by expectations of conventional femininity; it

was defiance rather than compliance, a boldness which might be seen

as unfeminine. Glamour could be seen as both risk and self-assertion, or

as a resource which might be used by women, albeit on what was often

dangerous territory, in a persistently unequal society.

Reflected from Hollywood cinema during the first half of the twentieth century, glamour allowed ordinary women to indulge in dreams of

escape from everyday hardship and to express interest in sexual power,

the exotic, presence and influence. The cinema exerted a strong influence on popular fashion and taste, although in the UK war, rationing and

limited incomes exerted strong brakes on consumerism. For the upper

and middle classes in Britain, American glamour had a more limited

appeal. There was a longer tradition of associating class with breeding,

elegance and restraint; for the middle classes, respectability and keeping

up appearances were governing concerns in matters of dress and social

comportment.

In 1950s Britain the idea of glamour became somewhat tarnished by

its associations with cheesecake photography, pin-up nudes or scantily

dressed models in naughty magazines. Women’s magazines in the 1950s

were leery about glamour. At the high end of the market, fashion editors

emphasised class, elegance and refinement: models such as Barbara

Goalen exuded an image of aristocratic, ladylike breeding, a somewhat

mannered and haughty disdain. Lower down the social scale, representations of ideal femininity were associated with modesty, neatness and

3

Glamour

domestic respectability. Glamour might be viewed by the socially secure

as brash and aspirational. For all of its associations with luxury and privilege, it was something middle-class England disapproved of, suggesting

women on the make, who wanted too much, knew too much, wore

too little or the wrong sort of clothes, and ‘were no better than they

looked’.

The style disruptions of the 1960s youthquake had a dramatic impact

on images of feminine desirability. Fashion models from Jean Shrimpton

to Twiggy adopted a wide-eyed, startled-and-innocent look: the glamorous sophisticate was out of fashion as swinging dolly birds and flower

children took centre stage, and haute couture gave way to Carnaby Street.

Glamour stayed somewhat out of fashion from the 1950s through to the

1970s: the word itself was much less frequently used by fashion editors

and in women’s magazines. There was less need for coded sexuality in

a world of free love. With the rise of the women’s liberation movement

in the late 1960s (so-called second-wave feminism), glamour became

something of a dirty word, associated with the sexual objectification of

women’s bodies, Miss World competitions and the cattle market. Fashion

ideals began to emphasise the desirability of the natural look, with girls

in long and floating floral dresses; advertisements for cosmetics depicted

these women in hayfields and meadows. Fur and heavy perfumes went

very much out of fashion.

But glamour was staging a comeback: in the pages of the magazine Cosmopolitan, confident, aspirational and sexually aware women

took stock of their image and were emboldened to look anew at the

old clichés. In the music world, ‘glam rock’, and the performances of

exponents such as Marc Bolan, David Bowie and Alice Cooper, disrupted

expectations about gender and style. Glamour in the 1980s drew upon

diverse elements: traditions of stage and screen, American soap opera, a

new affluence, public obsession with celebrity, and a heady and unapologetic consumerism. Glamour was more widely available than ever before:

piled on and parodied, it ran to excess. There was more than an element

of craziness and hysteria in the glamorous creations of designers such as

Jean-Paul Gaultier and Gianni Versace, in the productions of Dallas and

Dynasty, in the performances of Madonna and Elton John. Glamour was

cranked up and camped up, less an escape from the humdrum than a

clamour in popular culture from which it was difficult to find an exit. 4

Introduction

In the first decade of the twenty-first century the word ‘glamour’

was so widely used that it came to dominate the discourse of magazines

aimed at women, whatever their class, age or colour. Has the word lost

edge and meaning? Has glamour been democratised and, if now accessible to the many, does this reflect a new confidence and self-assurance

amongst women, or are they imprisoned and undermined by its dictates?

Will global economic problems fuel interest in austerity, vintage and

sustainable fashion, or intensify the desire for glamour as distraction and

consolation? This is a history not a horoscope, but some of these issues

are discussed in the final chapter of the book.

The organisation of the book is loosely chronological. It begins as

the word ‘glamour’ itself started to come into general use, at the beginning of the twentieth century. Before that, the word was used sparingly.

Lord Rosebery had a racehorse called Glamour, and scrutiny of the use

of the word in The Times Digital Archive around the 1890s and 1900s

shows that references to this animal accounted for much of its currency

in these years. The first chapter of this book outlines the historical

context in which the word ‘glamour’ rooted and took more of a hold, a

context of widening horizons, new technologies, and shifting aspirations

and assumptions: what contemporaries and subsequent historians have

generally referred to as ‘modernity’. The catalogue of the Newspaper

Division of the British Library shows that a large number of magazines

and newspapers founded in the 1920s and 1930s were given the prefix

‘Modern’: Modern Home, Modern Marriage, Modern Woman, Miss Modern

and so forth. Representations of the ‘modern girl’ in her various incarnations in the 1920s – flapper, vamp or ‘dancing daughter’ – presaged

the impact of the screen sirens and glamour icons of the 1930s. The

Oxford English Dictionary records an early use of the term ‘glamour girl’

in a magazine published in 1940, which noted the emergence ‘of the

new glamour-girl, as one must call her nowadays, as thin and slender as a

flake of silver leaf, as blanched as an almond, as “platinum” as a wedding

ring’.9

This book has a broad focus because its aim has been to bring

together a number of lines of enquiry, about the representation and

construction of different femininities, about the shaping of aspiration

and desire, and about the relationships between social conditions,

fashion and material culture. When I first started out on this study, a few

5

Glamour

of my colleagues raised their eyebrows. As an academic social historian,

most of my previous research had focused on gender, family and education. ‘So it’s out of the bluestockings and into the fishnets, is it?’ quipped

a friend in the corridor.10 But the change of direction is not as radical as

it might first appear: education is also about dreams and aspirations (not

just the targets and skills of contemporary policymakers), and fashion,

cinema and magazines, like educational institutions, offer glimpses of

different worlds, different models and different cultural understandings

about ways of being female.

This book stems in part from a fascination with material and visual

culture, clothes, cosmetics, popular fashions and inexpensive jewellery.

Flea markets, junk shops and car boot sales have always distracted me,

offering a rich source of social history. Piles of moth-eaten old furs,

shoe boxes of paste clips, strands of fake pearls, and pretty, empty scent

bottles speak about women’s dreams in the past and are highly evocative:

especially the scent bottles. I am a pharmacist’s daughter, and one of my

earliest pleasures was playing with the discarded perfume display bottles

and cosmetic samples which my father would bring home. I particularly remember a set of Chanel No. 5, Cuir de Russie, Bois des Iles and

Gardenia, magical names and haunting fragrances in elegant bottles,

each with a ground glass stopper.

Perfume, as is well known, triggers memory, and sometimes a

profound sense of loss and desire. Glamour has been usefully defined as

a visual language of seduction but it also includes a dimension of sensuality and magic through touch, texture and scent.11 There are a number

of published histories and celebrations of classic perfumes, but less has

been written of the cheaper and popular scents worn by women since

the early 1900s. In 2003 Newcastle Public Library hosted a display celebrating the history of popular scents, perfume bottles and related products arranged by an enthusiastic local collector. Visitors were greeted

by a large display of Evening in Paris, a scent created by the famous

Russian parfumier Ernest Beaux (who also came up with Chanel No. 5).

Evening in Paris, marketed by Bourjois and widely available from 1929

to 1939 and through the postwar years, is remembered by almost every

woman over the age of fifty, and even the empty blue and silver bottles

are now eagerly sought by collectors. The exhibition in Newcastle was

enormously popular and moved many visitors to muse on the dreams

6

Introduction

they had cherished in girlhood and to share their memories of growing

up in the last century.12

Much of women’s social history is embedded in clothes, cosmetics

and material culture. Dress history is now an important area of study

in its own right, and there are many invaluable studies of the history of

fashion and clothing.13 There are also numerous magazines and books

addressed to collectors of such artefacts as powder compacts, jewellery,

scent bottles and the like. This book is obviously not simply a history of

fashion nor is it a collectors’ book, but I have found the focused collectors’ guides very useful. Indeed the breadth of my own focus, and a

synthetic approach, has meant a considerable reliance on the work of

other scholars, which I hope is fully reflected in the bibliography.

7

1

The origins of glamour:

demi-monde, modernity, ‘It’

The word ‘glamour’ was obscure before 1900. It meant a delusive charm,

and was used in association with witchery and the occult. Sir Walter

Scott is generally credited with having introduced the word into literary

language in the early 1800s.1 In Victorian times the word was often used

in cautionary tales. In a poem called ‘A Victim to Glamour’ (1874) by a

long-forgotten versifier, Annie the mill girl turns her back on the trusty

blacksmith who is courting her after she is seduced by the darkly handsome son of her wealthy employer. Shame and ruin follow as the two

men fight it out, and an ill-aimed shot nearly kills Annie. After a long

and painful convalescence she sees the light and is reconciled with the

distinctly unglamorous, humble but reliable Walter.2 Texts of this kind

warned against glamour as dangerously alluring, leading innocents

astray from virtue, and emphasised the perils in store for anyone with

social aspirations above their lot in life.

The period from 1900 to 1929 saw the beginnings of the modern

idea of glamour, in the opulence and display of the theatre and demimonde, in Orientalism and the exotic, and in a conscious espousal of

modernity and show of sexual sophistication.3 During this period, the

word’s meaning expanded to describe the magic of new technologies: the advent of moving pictures on the silver screen, new forms of

Glamour

transport through air, on vast, luxurious ocean liners and in fast cars;

travel to distant and exotic places. Glamour could attach to both people

and objects, and its connotations were by no means exclusively feminine.

Pilots and rally drivers could be described as glamorous, especially the

former. Later, in the 1930s, dashing young officers of the RAF in their

grey-blue uniforms stitched with silver wings would become stereotypes

of the glamorous male.4 Even so, the term ‘glamour’ came to be associated more commonly with women and with a type of feminine allure.

Stars of the stage could be glamorous: actresses, or singers in opera

and the music hall. The designer and photographer Cecil Beaton

recorded his childhood passion for the music-hall artiste Gaby Deslys,

‘the first creature of artificial glamour I ever knew about’, whose ‘taste

ran amok in a jungle of feathers, diamonds and chiffon and furs’.5 The

young fashion designer Norman Hartnell confessed to a similar infatuation, recalling Deslys looking ‘like a humming bird aquiver with feathers

and aglitter with jewels’ setting off ‘her custard blonde hair’.6 Her staggering toilettes were legendary; even her pet chihuahua was observed to

sport a pair of pearl-drop earrings. Beaton identified Deslys as a transitional figure, her style and demeanour deriving partly from the demimonde of courtesans and cocottes of the 1890s, but in her theatrical

performances the precursor of a whole school of glamour that was to

be exemplified later by Marlene Dietrich, Rita Hayworth and the other

screen goddesses of Hollywood.7 Glamour, for Beaton as for many others

at the time and since, conveyed sophistication, artifice and sexual allure.

Extravagant displays of femininity were common in the Edwardian

demi-monde of actresses, courtesans and music-hall artistes. The actress

Sarah Bernhardt staged most of her public appearances as major performances, swathed in satins, lace and chinchilla. Beaton’s representation

of Deslys as standing out from other female performers of her day, and

as distinctly glamorous, stemmed not least from an appreciation of the

outré: the sexiness, confidence and air of indifference to convention that

this particular star exuded throughout her career. Norman Hartnell had

similar thoughts: at one point in his autobiography he suggested that

the word ‘glamour’ had become so vulgarised by over-use that it was no

more than ‘the small-change of advertising currency’. For him, though,

glamour remained inextricably connected with naughtiness.8

10

The origins of glamour

By the 1900s the prolonged proprieties of the Victorian period were

giving way to more open, though still highly coded, discussions of feminine sexual allure. Elinor Glyn’s sensational novel Three Weeks (1907)

was a watershed, thrilling readers with its purple-prose descriptions of a

mysterious Slav Lady arrayed in rich materials of the same colour, viewed

through silk curtains of ‘the palest orchid mauve’, squirming seductively

on a tiger skin.9 Here were all the stock props of Edwardian glamour:

heady Oriental perfumes pumped through Cupid fountains drugging

the senses of her young lover, couches of roses, ropes of pearls and rich

jewels twined through luxuriant, unbound hair. Above all, there were

the tiger skins themselves, replete with references to carnality, primitive

instincts, hunter and prey. Glyn herself owned a number of tiger skins.

She bought one with an early royalty cheque, and subsequently acquired

another eight, naming each after a man in her life: either fictional or

flesh and blood.10 ‘Would you like to sin with Elinor Glyn on a tigerskin?’ asked the doggerel verse of the day, ‘Or would you prefer to err

with her on some other fur?’ Elinor revelled in the sensuousness of

animal furs whether dead or alive: she once made a dramatic entrance

at a literary lunch party in London with her marmalade-coloured pet cat

curled around her shoulders.11

As a writer of best-selling popular fiction in Britain, and later as a

successful screenwriter in Hollywood, Elinor Glyn was even more than

Gaby Deslys a transitional figure, her colourful life spanning the worlds of

Edwardian luxury (country house parties, old aristocracy and new wealth)

and the new glamour of cinema. Glyn further bridged the worlds of the

kept woman and the celebrity writer and public figure. Her marriage

to the financially incompetent and emotionally unreliable Clayton Glyn

failed to provide the security and privileged lifestyle she had expected.12

As her husband’s debts mounted she relied on wit, talent and sheer hard

work to bail them out of ruin. Like her sister, the dress designer ‘Lucile’

(Lady Duff Gordon), she combined elements of a romantic, rather elitist

social vision with entrepreneurship and a very modern resourcefulness.13

In spite of her insistence on an exaggerated, conventional version of

sexual difference (man the hunter, woman his alluring prey), she was a

staunchly independent woman, carefully constructing her public image

and very much the author of her own life. Many of her fictional heroines

exhibit this same autonomy and independence. They refuse definition

11

Glamour

by birth, fate or fortune and make what they can of themselves and their

lives. The best example is the uncompromising Katherine in The Career

of Katherine Bush (1917). Of low birth (she is the grand daughter of a

pork butcher and the daughter of a Brixton auctioneer), Katherine sets

herself on a mission to rise up the social scale, acquiring classy manners

and accumulating what we might now call cultural capital in a process of

self-transformation. She is not shy of using her sexual powers to the full

to attract an aristocratic husband.14 There are echoes in this of Glyn’s

own love life – Katherine’s goal is the distinguished Duke of Mordryn,

loosely modelled on Glyn’s own amour of the 1900s, a former Viceroy

of India, Lord Curzon. Curzon eventually deserted Elinor and married

someone else. Elinor named one of her tiger skins Curzon.

Glyn’s romantic fiction, together with her pronouncements on the

nature of love, romance and attraction – famously referred to as the ‘It

quality’ – were eagerly devoured by an attentive public. ‘It’ was much

discussed, especially after Clara Bow was immortalised as the ‘It’ girl in

the 1927 film It, based on Elinor’s story and screenplay. According to

Glyn, ‘It’ could attach to both men and women: a quality not merely

sexual, but ‘a potent romantic magnetism’. In the animal world, she

declared, ‘It’ was most potently demonstrated in tigers and cats, both

animals being ‘fascinating and mysterious, and quite unbiddable’.15 The

public read ‘It’– like ‘oomph’– to mean basic sex appeal.

The glamour of early, silent screen cinema drew upon a heavy exoticism. Invited to Hollywood in 1920 to try her hand at script writing, the

56-year-old Glyn was in her element. Vamps, mysterious Slavs, doomed

queens and gypsies were her stock in trade. Glyn’s first script, for The

Great Moment, starring Gloria Swanson, met with considerable success,

the producer (Sam Goldwyn) announcing that Elinor Glyn’s name was

synonymous with the discovery of sex appeal for the cinema.16 Beyond

the Rocks, which paired Swanson with Rudolph Valentino, followed in

1922. The feminine aesthetic of these years combined a touch of the

harem with the Cleopatra look: women were kitted out in unlikely slavegirl costumes, wreathed in beads, with serpent-of-the-Nile arm and ankle

bracelets and kohl-rimmed eyes. This vampish Arab princess look, associated with Theda Bara, Nita Naldi and Pola Negri, gave way in turn to the

image of the flapper, the fun-loving, pleasure-seeking modern girl.17

12

The origins of glamour

As many historians have emphasised, the new freedoms of work and

the vote were seen as having revolutionised the role of women in the

years following the First World War, and the state of modern girlhood

became a cultural obsession.18 Probably a more enduring stereotype

than that of the ‘bright young things’ of the 1920s, ‘the modern girl’

was associated with much more than just hectic partying, jazz and the

dance crazes of the decade.19 Representations of both stereotypes owed

something to the literature of Scott Fitzgerald and Evelyn Waugh, and

also to the impact of screen performances by Clara Bow in The Plastic

Age (1925), Mantrap (1926) and It (1927), by Louise Brooks (Pandora’s

Box and The Canary Murder Case, both 1929, Prix de Beauté, 1930) and

Joan Crawford, especially in Our Dancing Daughters (1928). What was

distinctively modern about these performances becomes clear when

they are contrasted with earlier silent-screen heroines of rustic simplicity

and doomed innocence such as some of the roles played by ‘America’s

sweetheart’ Mary Pickford, or by Lillian Gish (Broken Blossoms, 1919, or

Way Down East, 1920). Whereas these earlier heroines embodied the

traditional virtues and values perceived as under threat from the city

and modernity, the shop girls, beauticians and husband hunters played

by Brooks, Bow and Crawford were modern, metropolitan, and in their

element; defying convention and revelling in a new freedom. British

film-makers similarly featured a new form of intrepid female: cinema

historian Jenny Hammerton has shown how the cinemagazines of the

1920s and early 1930s, particularly Eve’s Film Review, featured a carnival

parade of women aviators, stunt drivers, lion tamers and martial arts

experts in a celebration of modernity and of widening opportunities for

girls after the war.20

Emancipation was sometimes more apparent than real. Women over

the age of thirty gained the vote in 1918, but fears of the consequences

of ‘a flapper vote’ (and of women voters outnumbering men) delayed

full female suffrage until ten years later. There was much unease around

the new freedoms. Both in literature and in film the heroines depicted as

enjoying them were often made to suffer for their self-assertion. Today,

A. S. M. Hutchinson’s 1922 novel This Freedom reads as a maudlin antifeminist tract, but it was a best-seller in the USA and Britain when first

published. It depicts a woman involved in career ambitions as bringing

death and destruction to her children.21 The original, silent version of

13

Glamour

the film, which became Prix de Beauté or elsewhere Miss Europe, was made

in 1922, starring Louise Brooks. It was later dubbed and appeared in

France in 1930.22 Brooks plays Lucienne, a typist bored by her conventional boyfriend’s aspirations for her and his possessiveness. In search

of adventure, she enters a beauty contest; her success, together with the

attention she gets from other men, drives the boyfriend wild. In the end,

she leaves him, but he seeks her out in a murderous passion of jealousy,

killing her as she sits with a new lover, watching her own performance

on a cinema screen. Iris Storm, the undeniably glamorous heroine of

Michael Arlen’s cult best-seller of 1926, The Green Hat, flaunts all the signs

of modernity: she has attitude, sexy clothes, red lipstick and a fast car.23

The car is a yellow Hispano-Suiza: driving it is a metaphor for agency and

sexual self-possession. But Iris is doomed, for precisely these qualities.

The somewhat complicated narrative ends with a confusing mix of selfsacrifice and social vengeance: Iris engineers her own suicide by hurtling

her car into an ancient ash tree, which stands for tradition, in all its

obduracy. There was a stage version of The Green Hat, and in 1928 a film

based on the novel, entitled A Woman of Affairs, starring Greta Garbo.

The glamorous woman of the 1920s might still wear clothes inspired

by Orientalism, which had become fashionable under the influence of

set and costume designer Leon Bakst, the Ballets Russes and couturier

Paul Poiret before the war. Rich, embroidered fabrics, encrusted with

beads and glitter, were part of this look. A new, boyish figure increasingly

replaced the Edwardian pouter-pigeon shape and, alongside bobbed or

shingled hair, came to epitomise the modern girl. Bias-cut gowns, introduced by Madeleine Vionnet in the 1920s, emphasised slender curves

unrestrained by corsets, with crêpe and satin flowing down the body.

An advertisement in The Times, in 1922, for an exhibition of Japanese

kimonos in Harrods aptly illustrates the connotations of exoticism

carried by the word ‘glamour’ at this time: a graceful line drawing of

a woman in a silk kimono is set against a stylised oriental background,

and the text invokes ‘the witchery of the Far East’ and ‘the glamour of

blue-skyed Nippon’.24

These fashions involved a reworking of traditional ideas of femininity. In the eyes of many observers the modern girl embodied a kind

of androgyny: her boyish look went along with boyish habits, she was

not afraid to drink or smoke or drive a car. Nor was she slow to exploit

14

The origins of glamour

new and highly controversial opportunities for mixed bathing, sporting

increasingly revealing bathing suits. The rising popularity of sunbathing

and swimming as leisure pursuits after the 1914–18 war both represented

and reflected new freedoms for women.25 Bathing beauty contests may

have offended some, but proved enduringly popular: they were often

filmed, and the archives of British Pathé and the British Film Institute

preserve much footage of ‘aquatic frolics’ and beauty line-ups from the

1920s.26 Cinemagazines such as the already mentioned Eve’s Film Review

and Topical Budget are a particularly rich source of images of the fashions and styles of the 1920s. Wearing pyjamas – in bed, if not on the

beach as well – was considered daring but almost de rigueur for stylish

young women. In her autobiography, This Great Journey (1942), the politician Jennie Lee recalls how her mother scrimped and saved in order to

equip her daughter to go off to university in Edinburgh in the 1920s.

Collecting a suitable set of clothes was akin to, if not a substitute for,

assembling a trousseau. Alongside more serviceable items her mother

proudly produced a voluminous white nightgown, elaborately embroidered and adorned with frills and pale blue ribbons. Jennie was aghast:

The stuff must have cost a fortune. And this was 1922, the very height

of the pyjama age. I would rather have died than be caught by my

fellow-students floating around in an outfit of that kind. I was staggered, and didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. My mother’s face was

the last straw … 27

A key sign of modernity in women was the wearing of cosmetics, particularly lipstick, probably the most significant issue marking the generation

gap between mothers and daughters in the 1920s. Iris Storm in The Green

Hat applies lipstick to a mouth described by her author as a drooping

red-silk flower.28 Tallulah Bankhead, who played the role of Iris in the

stage version of the book, used cosmetics freely. Cecil Beaton likened

her cheeks to ‘huge acid pink peonies’, adding that ‘her eyelashes are

built out with hot liquid paint to look like burnt matches, and her sullen,

discontented rather evil rosebud of a mouth is painted the brightest

scarlet and is as shiny as Tiptree’s strawberry jam’.29

Bankhead quoted this description in her autobiography, but left

out the words ‘rather evil’.30 Greta Garbo, playing the part of the siren

Felicitas in Flesh and the Devil (1926), touched up her lipstick in church

15

Index

Page references to pictures are given in bold italics

Abrams, Mark, 114

Acts of Parliament: Abortion Law Reform

Act 1967, 122, 134; Equal Pay Act 1970,

135; Sexual Discrimination Act 1975,

135

advertising, 2, 10, 32, 39, 135; and social

deference, 93; cosmetics, 4, 42, 65, 103;

cosmetic surgery, 144-5; exploitation

by, 166; mink, 38; perfumes, 44-5, 105;

shifts in, 151-3

Alexander, Sally, 55

Angeloglou, Maggie, 64

animal rights: Animal Liberation Front, 140;

Lynx, 140; Our Animal Brothers, 25;

Peta (People for the Ethical Treatment

of Animals), 140; see also birds,

threatened

animal skins: bear-skin, 46; leopard-skin, 35;

tiger-skin, 11, 31, 45-6, 101, 134

Arden, Elizabeth (Florence Graham), 17,

19, 29, 42, 85, 87, 93; Ardena Orange

Skin Food, 17; Ardena Skin Tonic, 17;

rivalry with Rubinstein, 17; sanctuary,

38-9; Velva Cream, 17; Venetian creams,

17

Ayer, Harriet Hubbard, 17

austerity: in financial crisis, 5; interwar, 29;

postwar, 2, 3; wartime, 62

Bartky, Sandra Lee, 159

Basinger, Janine, 73

Beaton, Cecil, photographer and designer,

10, 15, 43, 105

beauty: as pornography, 156; differs from

glamour, 45; ‘fashion-beauty complex’,

159; in economic depression, 29;

parlours, 131, 160; standards of, 41, 167

beauty competitions: bathing beauties, 41;

Miss America and disruption, 123,

159; Miss Black Britain, 129, 167; Miss

Jamaica, 130; Miss World contest and

disruption of, 4, 123, 130

Berger, John, 2, 156

Bernhardt, Sarah, 10

Biba boutique, 111, 125-6; Angry Brigade,

128; bombing of, 128; Turner, Alwyn,

128

birds, threatened: campaigns against,

21, 25; Hudson, Revd, 21; marketed,

21; slaughter for hat feathers, 21;

smuggled, 34; types: birds of paradise,

21, 33, 34; egrets, 21-3; humming-birds,

21; kingfishers, 21

Black, Paula, 160

Blakely, David, 101

‘bling’, 147

bodies: and feminism, 157; and swimming,

41; changing shapes, 14, 38; Collins,

Joan, 142; Conley, Rosemary, 142;

Glamour

curves, 38, 44, 134, 142, 160; diets, 17,

38, 142, 159; dysmorphia, 2, 143, 144;

eating disorders, 2, 143, 159; exercise,

17, 38, 142, 160; fitness, cult of, 142;

Fonda, Jane, 14; Marmola tablets, 39;

obesity, 143, 144, 159; older women,

142, 143; ‘physical culturists’, 38;

salons, 38-9; skincare, 17; slimness, 38,

84, 143, 159; slimming plans, 38-41, 85;

Stephanie Bowman Slimming Garment,

85; waist sizes, 83; see also women

boots, see shoes

Bourdieu, P., 157

Brighton, 59, 64, 112-13

Bristol University, 113

Buckley, Reka, 162

Burke, Thomas, 72

Buszek, Maria Elena, 91

Campbell, Beatrix, 148

Campbell, Colin, 156-7

Cannadine, David, 95

Carnaby Street, London, 4, 113

Carrington, Edith, 25

cars with glamour: fast cars, 10, 14, 147;

females as drivers, 13, 14, 164; Daimler,

98; Hispano-Suiza, 14; Lancia, 35

Chanel: jewellery designer, 87; perfume

house, 5-6, 21, 45, 68, 70

Chapkis, Wendy, 158

‘cheesecake’, 3, 79, 90-2, 107

Chernin, Kim, 143

Chitty, Susan, 97

cinema, designs of, 51; see film (etc.);

glamour

class, social, 3-4, 43, 55, 74-5, 81, 83, 90,

93, 97-8, 103, 166; and ‘breeding’, 3;

and race, 82; Britain 1950s, 55, 109,

110; cinema-going, 49-51; housing,

86; incomes, 2; norms of, 3; poverty,

166; reading habits, 153; snobbery,

112; social deference, 93, 164; social

exclusivity, 112; social mobility, 47, 163,

164, 165

Clayton, Lucie, 95-6

clothes, see dress

Co-operative movement, 2

Cohen, Lisa, 105

consumerism: 2, 121, 135, 156-7, 159;

as pleasure, 134; conspicuous

consumption, 145

contraception, 122, 134-5

cosmetic surgery, 41, 143-5, 158; as ‘feminist

practice’, 2, 161; facelifts, 143;

makeovers, 41, 43; Noël, Suzanne, 161

cosmetics, 15-19, 29, 41-3, 64-5, 68, 74-

224

5, 89, 102-3, 118, 125-6, 138, 152-3;

‘anti-ageing’ creams, 2, 160; colours

of, 79; film stars, 41-2; grunge, 146;

lip gloss, 42; lipsticks, 15-17, 64-5, 67,

79, 104, 118, 153; make-up counters,

64; mascara, 42; nail varnish, 64, 68,

96, 107, 138, 146; opposition from

moralists, 19, 67-8; Ponedel, Dorothy,

42; rouge, 64.; Sforzia, Tony, 74

cosmetics, brand names: Aveda, 125;

Bonkers eye make-up, 118; Clinique,

125; Gladys Cooper’s Face Powder,

64; Guitare lipstick, 153; Hard Candy,

146; Jelly Babies, 118; L’Aimant, 87;

Leichner, 42; Luxuria face-cream,

17; Max Factor Pancake, 42-3, 64;

Outdoor Girl, 118; Pond’s vanishing

cream, 64; Shalimar Complexion

Creams (Dubarry), 21; Snowfire

vanishing cream and face powder, 63,

152; Starkers foundation, 118; Tangee

lipstick, 63; Tattoo lipstick, 67; Tetlow’s

Swan Down Petal Lotion, 152; Tokalon

Black Lipstick, 153; Urban Decay, 146;

see also Arden; Rubinstein

cosmetics designers and suppliers: Body

Shop, 125; Estee Lauder, 125, 141, 143;

Gala, 89; Max Factor, 42-3, 64, 118;

Quant, Mary, 118; Recamier and Co,

17; Revlon, 103, 104, 118, 141; Revson,

Charles, 103; Roddick, Anita, 113;

Stillwell and Gladding, 17; Westmore,

House of, 42, 43; see also Arden; Coty;

Rubinstein

Coty, perfumes and cosmetics, 70, 71, 87,

105

Coward, Rosalind, 157

‘Crawfie’ (Marion Crawford), 96

Crawford, Carol Joan, 130

Curzon, Lord, 12

dance: Ballet Russe, 14; Berkeley, Busby,

41, 128; lunchtime dancing, 113; teadances, 113

Davis, Kathy, 145, 161

De Beauvoir, Simone, 122-3

De Wolfe, Elsie (Lady Mendl), 44

debutantes, 109-10

Demeulemester, Ann, 147

dentistry makeovers, 41

deodorants: and perspiration, 97; vaginal,

135; see also perfumes and scents

department stores, 59, 64, 87, 140, 166; D.H.

Evans, 79; Debenham and Freebody,

59, 87, 140; Derry and Toms, 128;

Harrods, 146; Harvey Nichols, 140-1,

Index

146; Lewis’s, Birmingham, 58; Marshall

and Snelgrove, 59, 112; Selfridges, 146;

Woolworth’s chain store, 64, 70, 76

Deslys, Gaby, 10-11

diamonds, see jewellery

diets, see bodies

Dior, Christian, 95, 110; jewellery, 87; New

Look, 81, 83, 85-7, 90, 96; perfumes,

104, 141

Docker, Sir Bernard, 98

Docker, Lady Norah, 98, 99, 164

dress designers: Alaïa, Azzedine, 136; Ashley,

Laura, 124; Balenciaga, 88; Bakst,

Leon, 14; Beaton, Cecil, 105; Darnell,

Douglas, 131; Dolce and Gabbana, 141,

162; Edelstein, Victor, 149; Emanuel,

David, 148; Emanuel, Elizabeth, 148;

Fath, Jacques, 87; Gaultier, Jean-Paul,

4, 150; Givenchy, 114; Griffe, Jacques,

114; Hartnell, Norman, 10, 86, 95;

Head, Edith, 33; Hogg of Hawick, 117;

Hulanicki, Barbara, 107, 111-13, 120,

126, 128; Jean Louis, 108; Kawakubo,

Rei, 147; Klein, Calvin, 146; Krizia,

137; ‘Lucile’ (Lady Duff Gordon), 11;

Marchioness velvets, 116; Miller, Nolan,

136; Miyake, Issey, 147; Molyneux,

79; Muir, Jean, 140; Oldfield, Bruce,

149; Poiret, Paul, 14; Quant, Mary,

113, 121, 126; Rech, Georges, 139;

Schiaparelli, 37; Stambolian, Christina,

149; Valentino, 138; Versace, Gianni,

4, 138, 149, 162; Vionnet, Madeleine,

14; Walker, Catherine, 149; Westwood,

Vivienne, 146; see also Dior, Christian

dress history, 6

dress stores: chain stores, 118; D.H. Evans,

79; Fenwicks, 68; Jaeger, 70

dress style: and feminism, 123, 134;

androgynous, 46, 136-9, 150; as

rebellion, 55; beachwear, 41, 107;

beatnik, 113; beads, 55, 88; bias-cut, 14,

38, 39; comfortable, 102, 143; ‘Cosmo

girl’, 133-4, 136, 141; dolly birds, 4;

fitting, 38; flapper, 12, 14; ‘flash’, 143;

flower children, 4; for working out, 142;

from patterns, 52, 55, 58; ‘froufrou’,

103; gloves, 87, 93; home produced, 55,

154; kimonos, 14; ‘kinderwhore’ look,

146; leather, 141; materials, 38, 41, 55,

87; ‘Mrs Exeter’, 102; New Look, 81,

83, 85-7, 90, 96; power dressing, 136-8,

139; pre-Raphaelite, 124; punk, 146;

pyjamas, 15, 55; scarves, 79; shoulder

padding, 137, 138; ‘slinky’ 38, 39,

47, 55; stockings, 40, 93; street, 114;

structural supports for, 38; swimming

costumes, 41; ‘tarty’, 90; trouser suits,

136; underwear, 14, 37, 38, 41, 55, 79,

81, 82, 113, 123; uniforms, 79; Utility,

64, 88; see also feathers; fur; millinery;

shoes

dressing tables, 45, 86, 113

eating disorders, see bodies

Ellis, Ruth, 101

England, Carmen, 129

ethnicity, see racial and ethnic issues

Faludi, Susan, 144-5, 158

fashion, 2; and feminism, 162; different

from glamour, 3; ‘fashion–beauty

complex’, 159; impact of glamour on

popular fashion, 52; shows, 138; see also

glamour

feathers, 10, 21-3, 33-5; as camp, 33; as

exotic, 34; black coq, 34, 35, 44;

marabou, 23, 44; ostrich, 23, 34, 131;

peacock, 33; swan, 35; seductive power

of, 33; see also birds, threatened

femininity: and exercise, 142; and flowers,

43; of models, 116; contradictions of,

102-3, 144-5; versus androgyny, 142; see

also bodies; glamour; women

feminism: and adornment, 122-3, 144, 160;

and beauty contests, 4, 123, 129, 130;

and capitalism, 156; and glamour, 4;

backlash in 1980s, 144; pragmatic, 134;

puritanical elements in, 160; radicalism

of, 135; second wave, 122-3, 133, 144,

157

film: and leisure, 51; Bollywood, 167;

British, 15; creating dissatisfaction,

51-2; daydreaming in, 51; Hays Code,

49, 163; Hollywood, 1, 3, 10, 11, 12, 28,

29-47, 49, 52, 65, 72-4, 77, 90, 142, 150,

152, 162; morality bans of, 46, 49; social

stability effect, 51; star system, 47; style

influence, 58; transgression in, 163;

women’s opportunities, 13

film actors: Cooper, Gary, 44; Gilbert, John,

33; Harvey, Laurence, 134; Hope, Bob,

123; Navarro, Ramon, 152; Valentino,

Rudolph, 12, 19

film actresses: Ames, Adrienne, 54; Baker,

Carroll, 114; Bankhead, Tallulah,

15, 37; Bara, Theda, 19, 33; Bardot,

Brigitte, 107, 112, 125; Bow, Clara,

12-13, 17, 47; Brooks, Louise, 13-14;

Cardinale, Claudia, 107; Carroll,

Madeleine, 38, 39, 65, 66; Collins, Joan,

106, 136, 142; Crawford, Joan, 13, 17,

225

Glamour

30, 37, 41-2, 47, 58, 73, 77; Davis, Bette,

42, 47, 73; Dietrich, Marlene, 10, 30-2,

34, 35, 37-8, 41-2, 44, 46, 67, 78, 90, 163;

Dors, Diana (Diana Fluck), 100, 101,

164; Dunne, Irene, 37; Durbin, Deanna,

58, 72; Farrow, Mia, 138; Fields, Gracie,

73; Fonda, Jane, 142; Francis, Kay, 58;

Garbo, Greta, 14, 15-16, 30, 34, 37,

41, 43-4, 46, 58, 72; Gardner, Ava, 108,

113; Garland, Judy, 42; Gish, Lilian,

13, 43, 52; Grable, Betty, 91; Grahame,

Gloria, 108; Hack, Shelley, 141; Harlow,

Jean, 30 46, 163; Harris, Theresa, 46;

Hayworth, Rita, 10, 93, 95, 108, 113;

Hepburn, Audrey 93, 107; Hepburn,

Katherine, 73; ‘It’ girls, 12, 38, 65; Kelly,

Grace, 90, 93, 111; Lamarr, Hedy, 33,

43; Lamour, Dorothy, 91; Lawrence,

Gertrude, 37, 45; Lollobrigida, Gina,

107; Lombard, Carole, 30, 37, 43,

57; Loren, Sophia, 107; Mangano,

Silvana, 107; Mansfield, Jayne, 164;

Maguire, Dorothy, 91; Matthews, Jessie,

73; Mitchell, Yvonne, 102; Monroe,

Marilyn, 32, 85, 92, 95, 107-8, 150;

Morice, Annick, 112; Murray, Mae,

33, 44; Naldi, Nita, 12; Negri, Pola,

12; Pickford, Mary, 13, 43, 52; Rogers,

Ginger, 31, 58, 73; Sabrina (Norma

Sykes), 99, 164; Shearer, Norma, 31;

Stanwyck, Barbara, 46, 163; Sullavan,

Margaret, 58; Swanson, Gloria, 12, 17,

31, 35, 41, 46, 168; Taylor, Mary, 59;

Thaxter, Phyllis, 58; Turner, Lana, 45,

58; van Doren, Mamie, 108; West, Mae,

33, 38, 42, 44, 46, 126, 150; Young,

Loretta, 37

film costumiers: Adrian, 30, 37, 38; Banton,

Travis, 31, 35, 37, 47, 57; Travilla,

William, 32

film directors, etc.: Berkeley, Busby, 41,

128; Cukor, George, 107; De Mille,

Cecil B., 33; Fellini, Federico, 126;

Goldwyn, Sam, 12, 74; Hays, Will H.,

49; Hitchcock, Alfred, 39; Thompson, J.

Lee, 102; von Sternberg, Josef, 35; von

Stroheim, Erich, 33; Zukor, Adolph, 37

film studios: Elstree, 52; MGM, 30, 42;

Paramount, 37, 42, 43, 59; Walt Disney,

68, 93; Warner Brothers, 46, 163

Finklestein, Joanne, 157

flowers, 3, 43-4; American Beauty rose,

43; and femininity, 43; exotics, 43;

gardenias, 44; hyacinths, 78; lily, 35, 44;

orchids, 43-4; peonies, 15; roses, 44, 87;

see also perfumes and scents

Freedman, Rita, 158

226

Friedan, Betty, 122-3

Fromenti, artist, 89

fur, 23, 25-7, 35-8, 58-64, 88-9, 119-20,

138, 140; advertising of, 38, 59; and

feminism, 123; auctions of, 37; baby

seal, 62; Blackglama mink, 138; catfur, 62; cheaper pelts, 23-4, 59-62, 89;

chinchilla, 10; demand for, 23, 37, 59,

62, 89, 138-40; fake 89, 138; farming,

59, 89; mistresses, 119; fox, 37, 41, 59,

60, 88; for fur bikini, 101; fur coat,

23, 35-7, 36, 61, 62, 119, 140, 143; fur

collar, 36, 37, 59; fur muff, 37; fur ties,

60; gorilla, 37; marmot, 61; mink, 37-8,

62, 88, 89, 98, 101, 119, 140; mole, 59;

monkey, 37; musquash, 25, 61; ocelot,

88; opossum, 62; paws and tails, 24,

25, 37; rabbit (coney), 59, 62, 89, 101;

retailers, 59; Russian lamb, 62; sable,

23, 37, 104, 140; squirrel, 61, 62; Utility,

64; wallaby, 62; see also animal rights;

animal skins

fur breeders and trappers: Hudson’s Bay

Company, 25; location of, 59; number

in UK, 59; raided farms, 140

fur trade magazines: 23, 37, 59, 60-1, 203-4

furriers and fur stores: Bradley’s, 88;

Imperial Fur Traders, 59, 60-1; J.G.

Links, 88-9, 119; Maxwell Croft, 138;

Revillon Frères, 25, 26-7, 28, 62, 140;

Samuel Soden, 62; Ste Grunwaldt, 36;

Swears and Wells, 62

Gabor, Mark, 92

Gabor, Zsa Zsa, 99

Gardner, Joan, 65

gender: confusions in, 4, 135; differences in

dress, 166; inequities by, 163; norms of,

3; politics, 25; social changes, 164-5

Giddens, Anthony, 157

‘glamazon’, 137, 138

glamour (where not accounted for under

other headings): and beauty, 1, 45; and

cinema, 1, 30, 47; and escape, 167; and

fashion, 1-3, 29; and femininity, 1-2,

28, 45; and feminism, 2, 4; and magic,

1, 6, 9; and modernity, 162; and new

technologies, 9­-10, 162; and personality,

45, 65, 66; and patriarchy, 162; and

sexuality, 1, 3, 6, 9, 10, 46; and smoking,

14, 21; and travel, 28; androgyny of,

14, 46, 141, 150; as artifice, 1, 41, 101,

156; as aspiration, 3, 47, 163, 167; as

defiance, 67; as envy, 2, 47; as exotic,

9, 21, 28, 162-3, 167; as fantasy, 162;

as imperative, 155; as imprisonment,

Index

155; as luxury, 3, 45, 46; as nostalgia,

162; as perilous, 9; as pornography,

158; as power, 3; as provocation, 67; as

transgressive, 3, 10, 14, 167; defined,

6, 29; democratisation of, 5, 156, 167;

early meanings, 1, 9, 152, 156; feminine

style, 21; ‘glam rock’, 4; in and out of

fashion, 4, 28, 101; in demi-monde,

10; in men, 1, 10; in unequal society,

3, 4, 23; industries of, 166; name of

racehorse, 5; Orientalism, 9, 11, 14,

21, 28, 44, 167; racial differences of

meaning, 131; versus ‘breeding’, 46-7;

versus ‘daintiness’, 3, 72, 75; versus

‘elegance’, 101

Glendinning, Victoria, 120

Glyn, Clayton, 11

Glyn, Elinor, 11-12, 65

Graves, Robert, 17

Great Lakes Mink Association, 37-8

Greer, Germaine, 122-4

Gross, Michael, 104

Gundle, Stephen, 141, 162

hair: Afro-Caribbean salons, 129, 131;

‘Amami night’, 76; Antoine, 166;

Burden, Betty, 86; colours and tints, 10,

64, 142; curling, 64, 78; eyebrows, 64,

78; ‘glamour bands’, 79; hairdressers,

44, 86; perms, 65; styles, 14, 36, 58, 76,

142, 166; tiaras, 93; treatments, 17, 58

Hale, Sonnie, 73

Hammerton, Jenny, 13

Harper, Sue, 101

Harrisson, Tom, 77-8

hats, see millinery

Hauser, Gaylord, 38

Hayman, Fred and Gayle, 141

Hodge, Alan, 17

Hoggart, Richard, 91-2, 154

holidays abroad, 107, 164

Hollander, Anne, 30

Hollywood, see film

Horwood, Catherine, 74

Hulanicki, Barbara, see Biba; dress designers

Hutton, Barbara, 42

Internet, bringing ‘celebrity’, 147

Ironside, Janey, 78

Irvine, Susan, 141

‘Jane’ cartoon, 92

Jenkinson, A.J., 153

Jephcott, Pearl, 153

jewellery, 31-2, 87-9, 122; and vulgarity, 8990; as narcissistic, 122, 159-60; ‘bling’,

147; bracelets, 87; brooches, 87, 89;

diamonds, 10, 29, 31-3, 93, 99, 122,

131, 147, 158; earrings, 10, 87, 89, 113;

emeralds, 32; engagement rings, 32, 93,

122, 158; jet, 44; junk, 47; necklaces,

33, 87; pearls, 32, 35, 79, 86, 87; showy,

87, 138

jewellery, designers and jewellers: Asprey,

138; Bulgari, 138; Cartier, 138; Chanel,

87; Chaumet, 138; De Beers, 32, 122;

Dior, 87; Fath, Jacques, 87; Maer,

Mitchell, 87; Mann, Adrian, 87; Trifari,

87; Winston, Harry, 32

Jewesses, see racial and ethnic issues

Jones, Claudia, 129-30, 131, 167

Jong, Erica, 124

journalists and editors, 83; Bashir, Martin,

149; Boycott, Rosie, 156; Brown, Helen

Gurley, 121, 134; Carr, Diana, 152;

Cleave, Maureen, 111; Cleland, Jean,

70; Dark, Marion, 152; Dimbleby,

Jonathan, 149; Durbar, Leslie, 89;

Garland, Ailsa, 77, 83; Garland, Madge,

83, 105, 120; Grieve, Mary, 2; Hobson,

Violet, 52; Hutton, Deborah, 141;

Kurtz, Irma, 135; MacDowell, Colin, 33,

35, 95; Mansfield, Nigel, 152; Marchant,

Hilde, 86; McSharry, Deirdre, 134;

Miller, Beatrix, 140; Morton, Andrew,

149; Nast, Condé, 151, 154-5; Price,

Evadne, 152; Pringle, Alexandra, 120;

Settle, Alison, 68, 74, 83, 85-9, 105, 112,

114, 138; Tynan, Kenneth, 46; Vincent,

Sally, 135; Vreeland, Diana, 31, 33, 107;

White, Antonia, 42; Winn, Godfrey, 75;

Wintour, Anna, 140

Keeler, Christine, 119

Kings Road, Chelsea, 113

Kuhn, Annette, 47, 58, 73

Lakoff, R., 158

Langham Life Assurance Company, 135

Laye, Evelyn, 73

Lee, Jennie, 15

lipstick, see cosmetics

Lloyds of London, 91

Love, Courtney, 146

MacCarthy, Fiona, 110, 112

magazines: Boyfriend, 121; celebrity, 147;

cinema, 52-8; Condé Nast, 151, 154-5;

Cosmopolitan, 4, 133-6; Country Life, 95;

discourse of, 5; Esquire, 91-2; Eve’s Film

Review, 13, 15, 59; Flair, 115, 116-17,

121; feminine stereotypes in, 70-2; for

227

Glamour

men, 91-2; for women, 3; free gifts, 151;

‘girlie’, 91; Glamour(s), 142, 151, 154-5;

Glamour and Peg’s Paper, 89; Heat, 147;

Hello!, 147; Home Chat, 64; Honey, 122;

Life, 91; Marilyn, 89, 115; Mirabelle, 115,

151; Miss Modern, 5, 39, 65, 66, 75, 79,

164; Modern Home (etc.), 5; Nova, 115;

Now, 147; OK!, 147; Petticoat, 115, 121;

Picture Post, 42-3, 67, 74, 79, 86, 91, 96,

101, 106, 112; Playboy, 92; pop culture,

115; Poppet, 115; Pride, 167; Punch,

21; romantic fiction, 152-3; Romeo,

115; Roxy, 115; Spare Rib, 133-4, 156;

Valentine, 115; Vanity Fair, 93; Vogue, 36,

74, 77, 83, 89, 102, 105, 118, 136, 137,

138, 139, 140-1, 143, 146; Woman, 2;

Woman and Beauty, 101; Woman’s Own,

81, 85, 90, 94, 96; see also journalists and

editors

magazines, cinema ‘fan’: adverts in, 52;

advice on home fashion, 52; cheapness,

52; Film Fashionland, 52, 54, 55-8, 567; Girl’s Cinema, 52, 53, 55; higher

standards in 1930s, 55; love scenes,

52, 53; pattern services, 52, 55, 58;

Picturegoer, 52, 55, 100, 113; Women’s

Filmfair, 52, 55, 65

Mailer, Norman, 124, 128

Malone, Annie Turnbo, 17

March, Iris, 87

marriage: age of, 115, 121; and class, 78; and

cosmetics, 67; as a trap, 110; broken,

11-12, 73, 94; divorce, 165; impact

of war, 164; living together before,

122; multiple, 99; rates of, 165; social

betterment through, 105; to royalty, 93,

95; versus mistresses, 119

Mass Observation, 62, 68, 76-7, 79, 83, 85,

97, 142, 166

Max Factor cosmetics, 42-3, 64; perfumes,

118; marketing, 118

Mayer, J.P., 51, 58, 72

Mensing, Joachim, 141

Merriam, Eve, 85, 105, 118-20, 160

millinery, 21-3, 34, 58, 77-8; see also birds,

threatened

Miss World (etc.), see beauty competitions

models: ‘supermodels’, 138; Campbell,

Naomi, 140; Campbell-Walter, Fiona,

93, 95; Crawford, Cindy, 140; Dawnay,

Jean, 95; Dovima, 93; Goalen, Barbara,

3, 93, 94, 114; Hack, Shelley, 141; Leigh,

Dorian, 104; Marshall, Cherry (Miss

Susan Small), 83, 84, 96-7; McNeil,

Jane, 95; Moss, Kate, 145; Pugh,

Bronwen, 95; Shrimpton, Jean, 4,

228

116-17, 118; Stone, Paulene, 134;

Twiggy (Lesley Hornby), 4, 118

Molloy, J.T., 136

Moseley, Rachel, 93

Mulvagh, Jane, 87

museums (etc.): Brighton and Hove

Museum and Art Gallery, 64; British

Library, 5; Imperial War Museum, 67;

Newcastle Public Library, perfumes

exhibition, 6; Worthing Museum,

costumes, 55, 89

musicians: Baker, Josephine, 34, 131; Bassey,

Shirley, 127, 131; Beyoncé, 147; Black,

Cilla, 122; Bolan, Marc, 4; Bowie,

David, 4, 128; Brown, Foxy, 147; Cogan,

Alma, 103, 113, 120; Como, Perry, 115;

Cooper, Alice, 4; country and western,

131; grunge, 146; Hall, Adelaide, 34,

131; heavy metal, 146; jazz, 13, 34,

68; John, Elton, 4; Jones, Gloria, 128;

Knight, Gladys, 128; Liberace, 128;

L’il Kim, 147; Lopez, Jennifer, 147;

Madonna, 4, 146, 148, 150; motown,

128; opera stars, 45; Parton, Dolly,

131; pop, 115; Presley, Elvis, 115;

Previn, André, 138; R&B, 147; rap, 147;

Ross, Diana, 128; Vaughan, Frankie,

115; Warwick, Dionne, 128; Wynette,

Tammy, 131

N.W. Ayer, advertisement agency, 32

NAACP (National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People), USA,

131

‘nose art’, on aeroplanes, 79, 91

Notting Hill Carnival, 129, 131

Orbach, Susie, 143

orientalism, 9, 11, 14, 19, 21, 28, 44, 154,

167

Parker-Bowles, Camilla, 149

Partridge, Eric, 162

patriarchy: and capitalism, 2, 124, 145,

159; and consumerism, 121; and false

consciousness, 124, 145; and glamour,

162; and women’s bodies, 144, 150; as

conspiracy, 144-5; women as victims,

144-5; see also class, social; feminism;

women

Pearson, C. Arthur, 151, 155

perfumes and scents, 6, 19, 21, 44-5, 70, 76,

86, 89, 104-5, 125, 141, 147; bottles, 6,

45, 118; inexpensive, 6, 19, 68; luxury,

44; oriental, 44; Victorian, 44; see also

deodorants

Index

perfumes, brand names: Angel, 146; Bal

à Versailles, 104; Black Rose, 68; Blue

Mink, 105; Bois des Iles, 6; Bouquet

d’Orient, 19; Brownie, 147; BubbleGum, 147; Californian Poppy, 68, 69;

Carnet de Bal, 104; Chanel No. 5, 6, 21,

45, 70; Charlie, 141; Chypre, 70, 71;

CK-1, 146; Clear Water, 147; Cuir de

Russie, 6, 21, 45; Dans La Nuit, 45;

Diorissimo, 104; Dirt, 147; Electrique,

118; Evening in Paris, 6, 70; Femme,

104; Gardenia, 6, 44, 70; Giorgio

Beverly Hills, 141; Glamour, 45, 68;

Goya No. 5, 104; Grass, 147; Hasu-noHana, 19; Hypnotique, 118; In Love,

86; Jaeger Bracken, 70; Jolie Madame,

104; Joy, 105; June Roses, 86; Madame

Rochas, 104; Mary Garden, 45; Mink

and Pearls, 105; Mischief, 70; Mitsouko,

19, 21; Narcisse Noir, 68; Nirvana, 19;

Opium, 131; Orchis, 68, 70; Pavots

d’Argent, 68; Phul-Nana, 18, 19, 105;

Pink Mink, 105; Poison, 131; Primitif,

118; Shalimar, 21, 141; Shem-el-Nessim,

19, 20; Shocking, 44, 68; Tabac Blond,

21; Tsang-Ihang, 19; Waffle-Cake, 147;

Wana-Ranee, 19, 22; White Mink, 89,

105; Yardley’s lavender water, 19; Youth

Dew, 131; Zenobia flower waters, 19

perfumes, creators and marketers,

parfumiers: Beaux, Ernest, 6, 21, 70;

Collins, Douglas, 70, 76, 104; Daltroff,

Ernest, 21

perfumes, houses and manufacturers:

Atkinson, 69; Balmain, 104; Boots the

Chemists, 19; Bourjois, 6, 70; Calvin

Klein, 146; Caron, 21; Chanel, 6, 21, 45,

68; Coty 70, 71, 105; Demeter, 146-7;

Desprez, 104; Dior, 104, 141; Dubarry

Perfume Company, 21; Estee Lauder,

141; Goya, 68, 70, 104; Grossmith, 18,

19, 20, 22; Guerlain, 19, 21, 68, 141;

Hartnell, 86; Hayman, 141; Jovan, 105;

Max Factor, 118; Mme Gerard et Cie

(Boots), 19; Morny, 86; Patou, 105;

Raphael, 105; Revillon, 104; Revlon,

141; Rigaud, 45; Rochas, 104; Roger

and Gallet, 68; Saville, 70; Schiaparelli,

44, 68; Steiner, 89, 105; Thierry Mugler,

146; Worth, 45; Yardley, 19, 68; Yves St

Laurent, 141; Zenobia, 19

Petty, George, illustrator, 91

photographers, 46; Bailey, David, 140;

Beaton, Cecil, 10, 15, 43, 105; Bishop,

John, 137; Bull, Clarence Sinclair, 30,

31, 46; French, John, 94; Hardy, Bert,

86, 111, 120; Hurrell, George, 30, 46,

92; Keeley, Tom, 92, 107; Roye, Horace,

91-2, 101; Straker, Jean, 92; Vieira,

Mark, 30

‘pin-ups’, 3, 79, 91-2, 107, 164

political leaders: Kai-Shek, Madame Chiang,

42; Kennedy, John F., 108; Rosebery,

Lord, 5; Stevenson, Adlai, 108;

Thatcher, Margaret, 135, 138

post-modernism: and identity, 150; and the

self, 161

princes and princesses: Aly Khan, 94;

Charles of Wales, 148; Diana (Spencer)

of Wales, 148-9; Evlonoff, Michael,

93; Galitzine, George, 95; GourielliTchkonia, Artchil, 93; Kelly, Grace, 90,

93, 111; Margaret Rose, 85, 96, 112;

Rainier, 90, 93

Rachman, Peter, 119

racial and ethnic issues: activism, 131; and

beauty, 145, 167; and class, 82; and

fashion, 77; and glamour, 167; and

smart clothes, 77, 113; attitudes to

Jews, 77; black performers and singers,

128-31; black/white differences over

‘glamour’, 131; colour, 129, 131,

167; Pride, 167; racism, 82, 154, 167;

‘westernisation’ of looks, 167; see

also beauty competitions; musicians;

orientalism

Radner, Hilary, 121

Rechelbacher, Horst, 125

Revillon Frères, furs and perfumes, 25, 28,

62, 104, 140

Rice-Davies, Mandy, 119

Rodaway, Angela, 64

royalty: 42, 44, 67-8, 85, 93-6, 104, 112, 1489, 164; influence on fashion, 77; Kent,

Duchess of, 77; King George V, 68;

Queen Elizabeth II, 95, 164; Windsor,

Duchess of, 42, 44, 104; Windsor, Duke

of, 67; see also princes and princesses

Rubinstein, Helena, 17-19, 42, 79, 93; rivalry

with Arden, 17, 19; Valaze skin-cream,

16, 17;

Russell, Lilian, 43

Sambourne, Linley, 21

sanitary protection, Holly-Pax, 74

Scherr, R., 158

scooters, 107

Scott, Lady Alice, 95

Scott, Linda, 161

Scott, Sir Walter, 9

Seebohm, Caroline, 155

229

Glamour

Segal, Lynne, 124

sexuality, 3; ambiguity, 120; and modernity,

14; and power, 3, 91, 107; and scents,

44; and sexual exchange, 99-101, 105,

119; coded, 4; girls, 107, 114, 120;

morality, double standards of, 150;

women, 12, 107, 123; see also patriarchy

shoes: as obsession, 2; ballerina, 112, 113;

court, 110, 112; Doc Martens, 146; high

heels, 38, 77, 113, 143, 159; platform

soles, 38; slippers, 77

shopping, 2, 111; see also Biba; department

stores; dress stores

Silverman, Deborah, 145

slimming, see bodies

social class, etc., see class, social

Sontag, Susan, 33

Spencer, D.A., 51

Spring-Rice, Margery, 166

Stacey, Jackie, 72-3

Stearns, Peter, 159

Steedman, Carolyn, 85

Steinem, Gloria, 124

Straker, Jean, ‘photonudes’, 92

Summerfield, Penny, 79

Swarovski crystals, 131

Sweeney, Margaret (later Argyll, Duchess

of), 79

swimming pools, 41

Tapert, Annette, 58

Taylor, Lou, 79

television: Askey, Arthur, 99; Charlie’s Angels,

141; Dallas, 4, 136; Dynasty, 4, 136; Ways

of Seeing, 156

Thorp, Margaret, 45

Tinne, Emily, 23, 74

University Women’s Club, 75

USA (United States of America):

comparative views on glamour, 3; Food

and Drug and Cosmetics Act, 41; fur

craze, 23; lifestyles in, 41

USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics),

68

Vargas y Chavez, Alberto, 91

Veblen, Thorstein, 156

Waley, H.D., 51

Walker, Madame C.J., 17

Walker, Marlene, 129

Wall Street crash 1929, 29

230

Walsh, Jane, 55

Wilson, Elizabeth, 79, 112, 120, 161

Winship, Janice, 75

Wolf, Naomi, 144-5, 158

women: aspirations of, 163-4; black

women, 129-30; careers, 13, 121, 164;

commodification, 123; education,

115, 133, 135, 144, 153, 164, 165;

employment, 2, 13, 29, 133, 135, 144,

163, 164; entrepreneurship, 11, 46;

freedom, 13; living standards, 2, 3;

migrant, 81; objectification of, 2, 4,

46; older, 76, 102, 142, 166; property

values, 165; savings, 135; spending

patterns, 2, 165-6; status, 163-5;

suffrage, 13; sunbathing and swimming,

15; targets for business, 2; violence

against, 158; Woman’s Who’s Who, 59;

see also class, social; feminism; gender;

marriage; racial and ethnic issues;

sexuality

Women’s League of Health and Beauty, 41

Woodhead, Lindy, 17

Worthing, 113; Museum, 55, 89

Wray, Elizabeth, 62, 77

writers of fiction: Arlen, Michael, 14, 87;

Braine, John, 105; Brittain, Vera, 55,

75; Carter, Angela, 67, 168; Cartland,

Barbara, 148; Farrère, Claude, 19;

Fitzgerald, Scott, 13; Ginsberg, Steve,

141; Glyn, Elinor, 11-12, 65; Holtby,

Winifred, 55; Hutchinson, A.S.M., 13;

Loos, Anita, 32; MacInnes, Colin, 113,

115; Mansfield, Katherine, 75; Mitford,

Nancy, 113; Nabokov, Vladimir, 114;

Orwell, George, 72; Priestley, J.B.,

72; Tennant, Emma, 110; Waugh,

Evelyn, 13, 59; Weldon, Fay, 144-5;

West, Rebecca, 120; Wilde, Oscar,

157; Williams, Tennessee, 114; Woolf,

Virginia, 75; Worthing, Temple, 50

Wyndham, Joan, 64

youth: assertiveness, 114; ‘beat girl’,

117; emphasis on in 1960s, 164;

employment, 121; restrictions on, 115;

‘youthquake’, 4, 114