ARTICLE IN PRESS

Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

www.elsevier.com/locate/pursup

About ‘‘strategy’’ and ‘‘strategies’’ in supply management

Jean Nolleta,, Silvia Poncea, Manon Campbellb

a

Operations Management Department, HEC Montréal, 3000 chemin de la Côte-Sainte-Catherine, Montréal, Qué., Canada H3T 2A7

b

Indirect Procurement, Imperial Tobacco, Canada, Ltd., 3711 Saint-Antoine Street West, Montréal, Qué., Canada H4C 3P6

Received 24 April 2005; received in revised form 29 July 2005; accepted 7 October 2005

Abstract

This article addresses the context and content of a generic supply strategy and discusses its strategy-making process. Building mostly

on fundamental strategic management theories, the authors explain the role of supply strategy in its managerial context. In so doing,

some light is shed on the meaning and use of the terms ‘‘strategy’’ and ‘‘strategies’’. Also, a practical conceptual framework for supply

strategy formulation is provided. The generic checklist, built by segmenting supply management decisions, is intended to guide supply

professionals in addressing strategic issues to create value to customers, avoiding confusion and optimising resource allocation.

r 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Supply strategy; Strategy-making process; Strategy concept

1. Introduction

Classical frameworks guiding strategic thinking and

strategy-making have not taken into account Supply

Management at the same level as the Marketing, Finance

or Production functions. Moreover, after decades of

intellectual reasoning on strategy, research and practice,

the concept of strategy is still misleading. It is argued that

in an uncertain world, a strategy is too rigid to help dealing

with change, that the formulation process is time and

resource consuming, and that actually some top managers

do not even know what a competitive strategy looks like.

Some academics and practitioners have openly indicated

their disappointment with strategy, and strategic planning

indeed, whereas many organisations have simply abandoned it. Such a thought would have been considered

foolish a few decades ago.

Interestingly, at the same time these discussions about

the potential failure of—and the misunderstanding

about—strategy and strategic planning have been going

on, the strategic character of supply management has

largely been recognised. A wide consensus has been

Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 514 340 6279; fax: +1 514 340 6834.

E-mail addresses: Jean.Nollet@hec.ca (J. Nollet), Silvia.Ponce@hec.ca

(S. Ponce), Manon.Campbell@videotron.ca (M. Campbell).

1478-4092/$ - see front matter r 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2005.10.007

reached on this matter and high-performance organisations

know that resources must be allocated to develop a sound

supply strategy (Carter et al., 2000; Anonymous, 1998;

Hadeler and Evans, 1994; Doyle, 1990).

How can this apparent contradiction take place and how

is it possible to explain its misleading effect on strategy? In

other words, what is the meaning of strategy, particularly

when applied to supply management, and what is the place

supply strategy occupies in the strategy-making process of a

firm? And finally, what are the differences between ‘‘strategy’’

and ‘‘strategies’’ in supply management? The objective of the

analysis presented in this article is to discuss these issues and

to elaborate an answer to these questions.

We begin this article by addressing the concept of

strategy (Section 2) and generic approaches to strategymaking (Section 3), in order to make the fundamentals of

our subsequent discussion on strategy in supply management explicit. In Section 2, we position the discussions at a

managerial (or corporate) level to elicit the impacts on the

definition of a supply ‘‘strategy’’ y and ‘‘strategies’’. In

Section 3, by identifying and analysing three basic

approaches to strategy-making, our purpose is to characterise the actual organisational and decisional dynamics

of supply management.

In Section 4, we briefly review the evolution of strategic

thinking in supply management. In Section 5, we propose a

ARTICLE IN PRESS

130

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

conceptual framework, and the confusion surrounding

‘‘strategy’’ and ‘‘strategies’’ is specifically addressed.

Finally, in Section 6, practical questions are identified to

guide supply managers in getting maximum value out of

the supply strategy formulation process.

2. The concept of strategy

The excessive use—and even abuse—of the term strategy

has created much confusion among practitioners, misled

managerial decisions and actions, and fragmented academia. Worst, some managers have radically discarded it or

use it without taking advantage fully of what a strategy is

supposed to provide to organisations. A consultant in

strategic management has expressed his concern this way:

‘‘Put ‘strategy’ or ‘strategic’ next to something and it

sounds really important. So we have IT ‘strategy’,

manufacturing ‘strategy’, ‘strategic’ human resource managementy The word ‘strategy’ is overused, misused and

misunderstood.’’ (Kenny, 2003, p. 43). Notwithstanding,

the question ‘‘What is strategy?’’, and the efforts in defining

the term and understanding its dynamics have been a

recurrent topic of discussion among academics since the

mid-1960s!

To understand the controversies the concept of strategy

arises, four critical issues should be highlighted: First,

shortcomings are attributed to pragmatic definitions

provided by the classics (Ansoff, 1965, 1969, 1988;

Andrews, 1971, 1987), also called ‘‘the design school of

thought in strategic management’’. A fundamental reproach is that the rational and purposeful patterns of

decisions and actions promoted in strategy-making do not

allow for consideration of the environmental incertitude or

the managers’ own characteristics (Turner, 1997).

Second, the intrinsic complexity of strategic thinking,

strategy formulation and implementation processes, make

it difficult to grasp the dynamic nature of the concept. For

example, according to Evered (1983), strategy is a

continuous process by which goals are determined,

resources are allocated, and a pattern of cohesive actions

is promoted by the organisation in developing competitive

advantages. However, to Ansoff (1988), ‘‘Strategy is one of

several sets of decision-making rules for guidance of

organisational behaviour. For example: (1) Yardsticks by

which the present and future performance of the firm is

measuredy (2) Rules for developing the firm’s relationship

with its external environmenty (3) Rules for establishing

the internal relations and processesy (4) Rules by which

the firm conducts its day-to-day businessy’’ (p. 78).

Andrews (1987) has also dealt with the notions of time

and the fact that a strategy could be very specific; he has

argued: ‘‘As its meaning has dispersed throughout recent

usage, the word strategy still retains a close connection to a

conscious purpose and implies a time dimension reaching

into the future. At its simplest, a strategy can be a very

specific plan of action directed at a specific result within a

specific period of time.’’ (p. xi). Mintzberg (1987), in turn,

although agreeing on the dynamic nature of strategy, has

argued that an eclectic definition stemming from multiple

meanings of strategy should be accepted because a strategy

is a plan, a ploy, a pattern, a position, a perspective.

Mintzberg (1994a) has also characterised different kinds of

strategy-making processes, highlighting that a ‘‘realised

strategy’’ is ‘‘deliberate’’ and ‘‘emergent’’. Consequently,

managerial profiles, managers’ styles and commitment or

people’s cognitive frameworks play critical and determinant roles.

To solve the dualism on the subjective and objective

nature of strategy, Knights and Mueller (2004) have

proposed to approach strategy as a never-ending project,

as a mechanism for reconciling numerous stakeholders’

demands and participation. Nevertheless, Parnell and

Lester (2003) have reported that managers perceive

strategy either as an art or as a science. Whether it is one

or the other, or a combination, might well be influenced by

personality. Effectively, according to McCarthy (2003),

strategy is personality-driven and the vision, instinct and

imagination of entrepreneurs, rather than purely rational

variables, drive strategy.

Actually, Ansoff, in his revised work, The New

Corporate Strategy, recognised these facts, and stated in

the foreword: ‘‘The past 30 years of experience have shown

that strategic planning works poorly, if it works at all,

when it is confined to analytic decision-making, without

recognition of the enormous influence which the firm’s

leadership, power structure, and organisational dynamics

exert on both decisions and implementation’’ (Ansoff,

1988, p. v).

Third, while strategy is ingrained in competitiveness and

is performance driven, the achievement of goals and

strategic objectives does not necessarily warrant firm

success. The challenges extend far beyond simply achieving

the goals. On this matter, Michael Porter, one of the most

fervent defenders of strategy, has acknowledged that in a

constantly changing business environment, it is difficult to

come up with an appropriate strategy. According to this

author, strategy is about making deliberate choices and

trade-offs intended to provide continuity as well as a long

term sustained direction to organisations. ‘‘It’s about

deliberately choosing to be different’’, not to be confounded with operational effectiveness, i.e. ‘‘things that

you really shouldn’t have to make choices on’’ (see

Hammonds, 2001, p. 153). To Porter (1990, p. 41),

‘‘strategy guides the way a firm performs individual

activities and organises its entire value chain’’; he has also

argued that industry competitiveness analysis is critical and

that firm success, or failure, ‘‘is perhaps the central

question in strategy’’ (Porter, 1991, p. 95).

Yet, a very different perspective has been proposed by

Hamel and Prahalad (1995). Challenging Porter’s strategic

framework, the authors have sustained that understanding

industry structure through traditional competitive analysis

is not helpful in discovering the ‘‘why’’ of competitiveness.

Hamel and Prahalad have stated that the prerequisite for

ARTICLE IN PRESS

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

industry leadership is building ‘‘core competencies’’ to

restructure and transform industries. It follows that the

meaning of competitiveness and organisational characteristics should be equally important as the meaning of

strategy. On this basis, Hamel and Prahalad have

distinguished between the more ‘‘standard’’ strategic

planning approach and a crafting strategic ‘‘architecture’’

approach. These two approaches both have—or should

have—an impact on the way a supply strategy is devised. In

any case, the identification of these approaches contributes

to grasp the implicit dimensions of the concept of strategy

per se.

Fourth, as the business environment has become more

and more dynamic, networked and complex, so does

strategy; in fact, strategy has also intrinsically become a

change process. McCarthy (2003) has even argued that

strategy formation process is crisis-driven. A literature

review shows that recent publications have addressed the

issue in a variety of interesting ways, either highlighting its

complexity or being prone to its simplification through the

adoption of best practices. Ambrosini and Bowman (2003),

e.g. have reported evidence on agreement and disagreement

between executives about corporate strategy revealing a

lack of clarity—not to say ambiguity—, and probably

uncertainty in conveying strategies throughout the organisation. Beinhocker and Kaplan (2002), instead, have

addressed the mismatch between time, efforts engaged

and disappointing results in strategic planning, arguing in

favour of two new goals. The first one is ‘‘to make sure that

decision makers understand the business, its strategy and

the assumptions behind its strategy’’ (p. 49). The second is

to increase innovativeness. Along the same line of concern,

and for knowledge-intensive companies, Rylander and

Peppard (2003) have suggested the necessity of bridging

vision and value-based strategy to intellectual capital and

organisational identity; consequently, the implementation

process should be better understood as an ‘‘embodying’’

process of strategy.

Recent studies largely support previous ones, such as

Govindarajan’s (1989) and White et al.’s (1994), sustaining

that managerial characteristics are critical in contributing

to strategy and performance. Yet, recent developments,

although recognising the importance of strategy formulation, are more directed to implementation and deployment

issues (Norton, 2002). In fact, Norton and Russell (2004)

have sustained a best practice approach to strategy

execution, where strategic management is challenged to

become a ‘‘core competency’’ in organisations.

In summary, management literature provides evidence

showing that notwithstanding more than four decades of

contributions, theoretical and practical debates on strategy

are still going on. Years of inquire, research and practice,

have led to acknowledge that the concept of strategy,

including individuals’ involvement, challenges practitioners

and academia.

It has recently been said that the perception of the

strategic nature of supply depends on the ‘‘firm’s strategic

131

goals and priorities’’ (Cousins, 2005, p. 403). Then, it

should not be surprising that a clear definition and

formulation of a supply strategy might present a number

of challenges. Among them, the necessity to first make

explicit the concept of strategy at the firm level to be able to

determine the strategic role a supply strategy could fulfill.

In order to help address the specific issue of supply

strategy and strategies, we are proposing, in the next

section, a classification of strategy-making approaches

based on the field of business strategy. This will make more

evident some of the implications for a supply strategy

formulation, to be discussed in Sections 4 and 5.

3. Generic approaches to strategy-making

Many studies have addressed managers’ characteristics,

and their implications on formulation, implementation and

deployment of strategies and generic strategies (for

instance, Masch, 2004; Mintzberg, 1999, 1987; Herbert

and Deresky, 1987). Strategy-making processes go from

intuitive decision-making to very sophisticated and rational

ones but, in all cases, strategy-making processes are people

dependant. Thus, since the very inception of the practice of

strategy, in the mid-fifties, two extremes approaches to

strategy formulation have been observed: the formal and

explicit one and the informal one. Ansoff (1969) described

them as follows: ‘‘Most successful firms pursue their

business in a coherent and consistent manner. A study of

such firms will usually reveal distinctive and individual

patterns of strategy, even though the process of strategy

formulation may not be explicit or recorded in company

documents. Since the middle fifties, a significant trend in

business firms has been towards explicit and formal

strategy formulation.’’ (p. 7)

In addition to these two approaches, a third one has

taken place, emerging notably in the 1980s, with the

concept of ‘‘world class’’ and based on the adoption of best

practices (Voss, 1995). It follows that three generic

approaches to strategy-making in organisations are elicited. As summarised in Table 1, the first one is the

experience-based and intuitive approach, which is mostly

informal. The second one is the rational, formal and

systematic, structured process-based approach. The third

one is the best practices-driven approach.

In principle, these approaches underlie three lines of

thought and action concerning strategy-making. The first

and the second approach are best understood through

Mintzberg’s arguments in explaining why strategic planning failed. According to Mintzberg, strategic planning ‘‘is

not the same as strategic thinking. Planning is

about analysis and thinking is about synthesis. The

outcome of strategic thinking is an integrated perspective.’’

(Mintzberg, 1994b, p. 107). By applying Mintzberg’s

conceptualisations, the first approach in Table 1 basically

corresponds to ‘‘strategic thinking’’. It describes the

natural and intuitive entrepreneurial action that cannot

be excluded from strategy-making because it is the very

ARTICLE IN PRESS

132

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

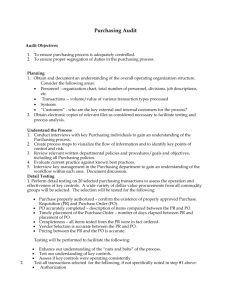

Table 1

Generic approaches to strategy-making

Approaches and characteristics

Experience-based and intuitive

Rational, formal and systematic;

structured process-based

Best practices driven

Main theoretical line of thought

and action

Process school; entrepreneurial and

emergent

Design schools; purposeful and

codified

Operations efficiency oriented

Description

Flexible; strong leadership

Formal; planned; communicable;

validation and coherence potential

Know how; measurable objectives

Main drawbacks

Risky; individual dependency

(entrepreneur)

Time consuming; procedural;

consolidation needed

Fragmented; requires efforts for

integration

source of differentiation. The second approach matches the

rational way to strategy-making mainly supported by the

design school. Still, this approach is equally relevant

because it allows for concretising the strategic exercise

into plans; it is intended to codify and make strategy

explicit and communicable. Therefore, both approaches

are complementary and co-existent rather than exclusive.

And in practice, they should compensate each other to

neutralise their respective drawbacks.

The third one in turn, the best practice-driven approach,

has in some measure been singled out by Porter (Hammonds, 2001) as well as by Hamel and Prahalad (1995),

who have argued that operational effectiveness (in fact,

‘‘efficiency’’ in Operations Management terminology) is

not strategy-making. Notwithstanding, Norton (2002) and

Norton and Russell (2004), among others, have demonstrated the contribution of some best practices, such as the

balanced scorecard, in formalising a strategy and working

on measurable and integrative efforts in strategy-making.

As such, best practices should be understood and adopted

as supporting tools rather than drivers in strategy-making.

On the other hand, the process of strategy-making

comprises: (1) A theoretical formulation of the strategy; (2)

the application or implementation of the formulated

strategy, and (3) the realisation or deployment of the

formulated strategy, the action. Thus, if the dynamics of

strategy-making is understood as a whole process, the three

approaches elicit three dimensions of the same whole. It

appears then that theoretical developments, in looking for

a better understanding of strategy and strategy-making,

have analytically fragmented the context, content and

processes involved, whereas practitioners deal with strategy

in an integrated and systemic environment. The underlying

fragmentation of partial approaches to strategy and

strategy-making (condemned to fail) appears to be the

root-cause. Disappointing results in strategy-making

(Atkinson, 2004; Beinhocker and Kaplan, 2002; Mintzberg,

1994b) are most probably associated and even explained by

a dysfunctional integration of its components, in other

words, people, processes, and/or means. More research is

needed on this subject but, meanwhile, we can ask

ourselves: could integration be contemplated in such a

huge process as strategy-making?

According to literature and some practitioners, the

rational answer is that integration happens throughout a

hierarchical decisions pattern in strategy-making. As a

point of departure for strategy-making in companies, the

classical design school of thought has clearly distinguished

two levels: corporate and exploitation strategies (Andrews,

in Anonymous, 1995; Andrews, 1987). Corporate strategy

sets hard goals—profitability, growth, product, market,

financial performance—, and soft goals—management

style, commitment, employee policies, community, environmental, societal and ethical responsibilities. According

to many authors (McCarthy, 2003; Hill, 2000; Hamel and

Prahalad, 1995; Porter, 1990; Andrews, 1987), orientations

in value creation to customers, definition of competitive

advantage, core competencies and risk considerations are

also included.

Following corporate strategy, strategic planning normally applies to individual business units—business strategy, according to Andrews (1987)—; the relative

importance of functions stems at this second level,

although functional strategies constitute by themselves a

third level. It is not uncommon to find marketing and

manufacturing strategies frameworks conceptualised, developed and implemented by companies under the umbrella of individual business units (White et al., 2003; Hill,

2000; Skinner, 1978); supply strategy indeed took some

time to get recognised (Watts et al., 1992). In any case, the

integration of strategies takes into consideration three

different levels of strategy, necessarily following a rational

and systematic approach in strategy-making.

It should be noted that, on one hand, in the supply

management field, with the exception of the conceptual

framework developed by Watts et al. (1992), surprisingly

few other authors (Cousins, 2005; Morgan and Monczka,

2003; Cavinato, 1999; Cox and Lamming, 1997; Cox, 1996;

Ellram and Carr, 1994; Rajagopal and Bernard, 1993) have

discussed about the link between supply strategy and the

strategy of the firm. On the other hand, in the management

field, supply management decisions are most of the time

embedded in corporate, business or other functional

strategies, these three fundamental levels in strategymaking being well accepted (Andrews, 1987). Considering

that the strategic nature of supply appears to be delimited

ARTICLE IN PRESS

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

by the strategy of the firm (Cousins, 2005), the strategymaking approach and its integration dynamics should be

determinant in recognising the role of a supply strategy.

Thus, in order to understand the underlying hierarchical

integration dynamics, a more specific discussion of the role

of supply strategy is presented in the next section.

4. Supply management and strategy

Except for Porter’s value chain model and his industry

competitive analysis framework (Porter, 1990), classical

managerial contributions have not explicitly discussed the

supply function, or procurement, or supply strategy.

Besides, conceptual frameworks appear generally detrimental to supply management functional strategy. For

example, in analysing Porter’s generic strategies (differentiation strategy and cost leadership strategy), Govindarajan (1989) has explained that differentiation requires

strong marketing and R&D skills, whereas low cost

requires efficiencies in buying, production, strong manufacturing and finance/accounting skills. Evidently, this kind

of analysis does not enhance the full potential of a supply

strategy in its contribution to a firm’s competitiveness by

differentiation; it rather limits the contribution to cost

reductions.

On the other side, specific developments, notably in

global network modelling, have indicated that ‘‘global

133

sourcing and distribution are included in global production

strategy’’ (Starr, 1984, p. 17), thus reinforcing the

subordinated place traditionally attributed to supply

management by operations and manufacturing strategy

classical frameworks (for instance, Hill, 1985, 2000; Hayes

and Wheelwright, 1984; Skinner, 1978).

Despite the aforementioned limitations, strategic concern for supply and procurement emerged in supply

management more than 30 years ago, as discussed in the

following sub-section.

4.1. Evolution of strategic thinking in supply management

In 1990, Doyle pointed out to the increasing attention

paid by executives to procurement strategies. However,

there have been important contributions to the development of strategic thinking in supply management (see

Fig. 1, for landmarks in this area). By 1992, Watts et al.,

emulating Skinner’s previous seminal work on manufacturing strategy (Manufacturing—missing link in corporate

strategy, Skinner, 1969), made the link between purchasing, corporate competitive strategy and other functional

strategies explicit. At about the same time, Monczka et al.

(1993) were among the first to highlight the key role of

procurement and supply in world-class firms. ‘‘World-class

supply management’’ and ‘‘world-class supplier’’ are

expressions that have now become common in indicating

Fig. 1. Evolution of the thinking about the strategic role of supply.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

134

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

the development of superior supply capabilities and

performance (Frazelle, 1998).

The increased attention by executives referred to by

Doyle (1990) had to come progressively from efforts by

many contributors, notably from the academic side.

Actually, Rajagopal and Bernard (1993, p. 13) have

established that purchasing strategy achieved a certain

level of ‘‘recognition and interest in the mid-1970s’’.

According to Ramsay (2001, p. 40), the title of ‘‘father’’

of purchasing’s potential contribution to sustainable

competitive advantage ‘‘line of research’’ comes to David

Farmer. Ramsay states that in a series of articles published

since 1976, Farmer made a strong ‘‘attempt to raise the

purchasing’s strategic profile’’ (Ramsay, 2001, p. 40).

Ellram and Carr (1994) also point out in the same

direction, establishing that the important shift observed

on purchasing strategic issues and role took place between

the mid-1970s and the early 1990s. During that period,

purchasing went from a perceived passive role to independency and later, from a perceived supportive role to a

recognised function.

It should also be pointed out that in 1978, the Harvard

Business Review published Corey’s seminal work about the

strategic decision of procurement centralisation. The same

year Corey published his book Procurement management:

strategy, organisation, and decision-making. Under the

heading of Procurement strategy models, Corey wrote: ‘‘A

strategy is a plan of action designed to achieve given goals

and objectivesy Procurement strategies vary so greatly

from one purchasing situation to anothery Thus, every

strategy has to be tailoredy However, all procurement

strategies seem to be variations and modifications of

the three basic modelsy, i.e. cost-based negotiations,

market-price-based negotiations, and competitive bidding.’’

(Corey, 1978b, p. 2).

Near the mid-1990s, a difference between ‘‘purchasing

strategy’’ and ‘‘strategic function’’ was made. Ellram and

Carr (1994) argued that the first ‘‘refers to specific actions’’

to support purchasing function objectives (p. 17) whereas

the second refers to key decisions and participation in the

‘‘firm’s strategic planning processes’’ (p. 17). The same

authors identified three distinct types of purchasing

‘‘strategy’’:

(1) ‘‘specific ‘‘strategies’’ employed by the purchasing

function;

(2) purchasing’s role in supporting the ‘‘strategies’’ of

other functions and those of the firm as a whole; and,

(3) the utilisation of purchasing as a ‘‘strategic’’ function of

the firm’’ (p. 10).

Practically at the same time, Hadeler and Evans (1994)

argued that, in capturing value in supply management and

sourcing, an effective ‘‘strategy’’ must be developed and

implemented. These authors also identified partnering,

supplier relationships and strategic alliances with suppliers

as strategies to focus and improve efficiency in procure-

ment management. It is then clear that over time, the terms

‘‘strategy’’ and its plural ‘‘strategies’’ became gradually

used more and more, notably by applying it to procurement strategies (Paliwoda and Bonaccorsi, 1994; Saarinen

and Vepsalainen, 1994; Spekman, 1985; Corey, 1978a, b).

And, the strategic thinking in supply management gave

quickly place to a greater involvement in strategy.

4.2. Evolution of the concern about supply strategy

By the end of the 1990s, authors were more concerned

with supply strategy content and context. Carr and

Smeltzer (1997) presented one of the first efforts in

operationalising ‘‘strategic purchasing’’. To this end, these

authors empirically developed four indicators (and 16

underlying variables, although all not inclusive) that

correlate to the level of strategic purchasing. These factors

are: status (how the function is perceived inside the firm),

knowledge and skills (knowledge of supplier markets,

analytical skill and purchasing performance measurement),

risk (willingness to take advantage of new opportunities,

foresight) and resources (including access to information).

Soon after, networks promoted probably one of the first

efforts in defining the concept of supply strategy (Harland

et al., 1999). Although descriptive in nature, Harland

et al.’s definition helps in improving the understanding of

sourcing context and highlights the new role of supply in

the business context of the 21st century. Interestingly, Carr

and Smeltzer (1999) found practically at the same time that

strategic purchasing is positively related to four supply

management variables: supplier responsiveness, supplier

communication, changes in the supplier market and the

firm’s performance.

It should also be noted that by the mid-1980s, Burt

(1984) introduced the notion of ‘‘proactive procurement’’,

considered a major contribution by pioneering pro-activeness in management. This notion was integrated to valuedriven approach and supply management by the mid1990s. Cox (1996) and Cox and Lamming (1997), in

particular, have argued in favour of a prescriptive

approach to supply management, asking for a dramatic

change to take place in the way firms managed supply. In

so doing, firms should recognise that for achieving a

sustainable and profitable advantage, supply management

professionals have to ‘‘constantly assess the relative utility

of a range of collaborative and competitive external—and

internal—contractual relationships’’ (Cox and Lamming,

1997, p. 62).

The dawn of the 21st century found purchasing and

supply management already of ‘‘major strategic importance’’ (Humphreys et al., 2000, p. 85). Indeed, new venues

and activities have enhanced both the strategic role of

suppliers, for instance in innovation (Croom, 2001), and

the strategic role of supply management professionals

(Ellram et al., 2002). Knowledge and skills developed

during the last ten and even fifteen years have made

possible the adoption and integration of best practices in

ARTICLE IN PRESS

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

135

Table 2

From ‘‘strategy’’ to ‘‘strategies’’

From ‘‘strategy’’y

to y

‘‘strategies’’

Type of strategy

Corporate strategy

Business strategy

Functional strategies, e.g. marketing

strategy, manufacturing strategy,

supply strategy

Scope

Systemic; holistic

Analytical; subordinated

In supply management, e.g. service

acquisition strategies, supplier

selection strategies, outsourcing

strategies, and so on

Analytical; fragmented

General definition

A framework for business. Broad

orientations; choices, product/market;

soft and hard objectives

A plan

A particular way of doing

Characteristics

Long term; provides continuity,

integrity

Medium term; integration and

coherence required

Very specific

Most relevant schools of

thought and key authors

Design/planning school

Ansoff (1965, 1969, 1988)

Andrews (1971, 1987)

Process school

Mintzberg (1999, 1994, 1987)

Industrial competitiveness

Porter (1996, 1991, 1990)

Supply strategy

Carr and Smeltzer (1997, 1999)

Cox (1996)

Cox and Lamming (1997)

Leenders et al. (2005)

Operations strategy

Hill (2000)

Hayes and Wheelwright (1984)

Skinner (1978)

Embedded in the previous column

Core competencies (resource-based

view of the firm)

Hamel and Prahalad (1995)

(for a more complete review, see Hart,

1995; and Ramsay, 2001)

Marketing strategy

Wind and Robertson (1983)

supply management (Ellram et al., 2002). Among them,

and probably the most interesting from the standpoint of

practicing the profession, is scanning leading-edge technologies and supplier market information. The advent of

business intelligence has opened new areas to supply

management to contribute to corporate success. Actually,

Cavinato (1999) envisioned a higher level of involvement

than supply strategic management named ‘‘knowledgebased business’’, where the function is involved in

strategically linking the firm to suppliers and networks

knowledge. But to reach this higher level, it is also

compulsory for supply management professionals to

master the strategy-making process and its implications.

In Section 3, we have argued that three levels have

become well accepted in strategy-making: corporate

strategy, business strategy, and functional strategies. In

order to integrate the contributions already discussed and

to illustrate their implications on strategic supply management, these three levels are described in Table 2 in terms of

scope, characteristics and schools of thought. Corporate

and business strategies, by their systemic and holistic scope,

are both characterised in the first column. Functional

strategies are found in the second column and, specific

issues or ‘‘ways of doing’’ in supply management, are

succinctly illustrated in the third column.

Main characteristics—fourth row in Table 2—show that

corporate and business strategies are directed towards the

long term, being intended to provide continuity and

integrity to the whole company. Functional strategies are

medium term plans; at this second level, broader definitions

of strategy should be translated into concrete and specific

actions. And, from functional strategies, a variety of ways

of accomplishing strategic tasks are devised; these ways—a

third level in supply management—being commonly

described as ‘‘strategies’’, probably to highlight their

impact and contribution to the performance of the firm.

Most relevant schools of thought and key authors are

indicated in Table 2 (last row), to show how we have built

explanations for supply strategy on four of the most

fundamental strategic management theories: the design/

planning school, the process school, the industrial competitiveness and the resource-based view of the firm. In so

doing, our objective is to make explicit the meaning of

‘‘strategy’’ and ‘‘strategies’’ in their applications to supply

management. This is why, in the next section, we discuss

how a supply strategy is formulated and implemented.

5. Supply strategy-making

The concept of strategy in supply management takes

form, in practice, through a strategy-making process.

Supply strategy is necessarily framed and should be crafted

following corporate and business strategies as well as

consolidated with other functional strategies. Therefore, at

least seven hierarchical steps should be performed to

formulate and implement a sound supply strategy, as

indicated in Fig. 2. Due to its subordination to corporate

and business strategies, and the necessity of functional

coherence and consolidation, this process should be

understood as a two-way process, i.e. it should go from

ARTICLE IN PRESS

136

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

Suppliers/Partners ---------------------------FIRM--------------------------- Partners/Customers

1. Strategy of the Firm

7. Implementation

Corporate Strategy

Business Strategy

2. Top-Down

6. Down-Top

cascade

consolidation

3. Functional strategies

Supply strategy

Operations strategy

Marketing strategy

5. Functional integration

4. Content:

Procurement

strategies, others

4. Content:

….

4. Content:

….

Fig. 2. A hierarchical decisional framework for strategy-making.

the general to the particular and then, from the particular

to the general, as illustrated in Fig. 2. This systematic and

rational process is not always completely followed in

practice; two reasons are advanced. Firstly, is the

embeddeness of supply in manufacturing and operations,

as explained in strategy classical frameworks, which have

incorporated supply management as an element of the

structure, at the same level as technology, processes and

facilities (Hill, 2000; Hayes and Wheelwright, 1984;

Skinner, 1978). Secondly, is the weak consolidation and

communication among functions, notably between marketing and production (embedding supply), as pointed out by

Hill (2000).

The hierarchical integration of the strategy-making

process, in Fig. 2, comprises steps 1–3, i.e. strategy

formulation of the firm, top-down cascade (strategic

objectives) and, functional strategies formulation, as

already discussed in Section 3. New issues in supply

management—i.e. globalisation, suppliers networks development, supplier relationship management, supply chain

management, scanning leading-edge technologies and

supplier market information, and e-commerce (Carter et

al., 2000; Cavinato, 1999; Cox and Lamming, 1997)—have

also placed new demands on the function and consequently, on professional supply managers. These new

demands need to be analysed, to determine its strategic

content, as well as the relevance to position them as

‘‘strategies’’ or ‘‘strategy’’. In all cases, it is critical to

realise that the way managers perceive competitiveness is

determinant. On this matter, Cousins (2005) has observed:

‘‘if a firm adopts a cost focused approach to its competitive

position it will unlikely consider supply as a strategic

process, because its competitive priority is to reduce

costyWhereas if a firm sees itself as a differentiator in

the market place, it is likely to take a more strategic view of

supply; supply will be seen as a source of competitive

advantage through inter-organisation collaboration management’’(p. 422).

As for steps 5–7 and in order to confirm the proposed

hierarchical decision framework to strategy-making in

supply management, empirical research is needed. These

steps comprise functional integration of strategic plans,

down-top consolidation and implementation of strategies.

Based on literature review and field observations, we focus

on step 4, of Fig. 2, i.e. supply strategy content, in the

following sub-section.

5.1. Supply strategy content

After Corey’s procurement strategy models (see Section

4.1), one of the earliest documented attempts to strategymaking in supply management has identified four procurement strategies: a team-oriented value analysis approach,

just-in-time and materials requirement planning techniques, total quality management and make-or-buy analysis

(Sutton, 1989).

By 1990, Doyle (1990), providing a more detailed

description of a procurement strategy, summarised five

critical components or ‘‘five disciplines’’, as follows: quality

improvement (variance reduction), velocity (concept-tocustomer cycle time improvement), all-in-cost (total-cost

purchasing practices), technology (access and active

monitoring) and risk reduction (an activity-managed

program approach).

More recently, in 1998, Carlos E. Mazzorin, Ford’s vice

president of purchasing for automotive operations, described key components of Ford’s supply strategy in terms

of cost control, quality improvement, and supplier development (Anonymous, 1998).

Other cases analysed point out, in general, to the same

components but traditionally, supply management has not

been deemed to be (externally) customer oriented. Yet, the

ARTICLE IN PRESS

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

consensual value approach promoted in the field as well as

‘‘pull strategies’’ being common place, suggest more and

more that customisation and service value to customers are

key drivers to strategy-making for the function. In order to

contribute effectively to build and sustain competitive

advantage and capabilities, supply management needs to

direct its efforts to provide the most value for each

individual customer throughout the value chain. Knowing

the customer is not an exclusive marketing task anymore.

Actually, collaborative management and product cycle

management involving cross-functionality (Rink and Fox,

2003) suggest that people, processes and means have to be

managed in such a way that supply will make intelligent use

of tangible and intangible resources, even intuition,

imagination and innovation stemming from supply and

procurement professionals.

It is also important to understand that under a value

perspective, not all purchasing decisions and supply

activities are strategic in nature. Indeed, some strategic

supply organisational decisions are not always of its

domain of responsibility. To illustrate our arguments, let

us consider, e.g. the outsourcing of purchasing or procurement. A recent survey of procurement directors, from

companies in 14 countries (US and European) indicates

that 22 per cent of companies (of a total of 219), outsource

some purchasing areas whereas more than a half of UK

companies and 64 per cent in France are likely to outsource

procurement by 2006 (Arminas, 2003). The nature of the

outsourcing decision directly threatens supply management; it is of course strategic for any company because of

its impact on supply capabilities (Morgan and Monczka,

2003). But at a corporation and business unit level, the

decision may even be discussed at what could be considered

a tactical level. The same could happen with partnership

and supply chain management decisions affecting company

performance. Therefore, it comes up to supply professionals to proactively frame and align supply decisions to

the firm strategy as well as to creatively devise supply

management contribution and strategic content. How is it

possible to do this? We advance key elements in the

following sub-section.

5.2. Conceptual framework for supply strategy formulation

To be even more explicit, supply strategy is composed of

a series of plans, consolidated in a master plan for

coherence and integrity, thus ensuring and demonstrating

its contribution to corporate and business strategic

objectives. As suggested in Table 3, a supply strategy

should start by segmenting decisions and focusing according to a company’s characteristics, management style and

culture.

A generic framework for supply strategy content is

proposed in Table 3. Although systematic research in this

area is needed, the tool constitutes a checklist which could

be used at least as a starting point. In the left column, key

elements of corporate and business unit strategies are

137

described. In the right column, based on Leenders et al.

(2005) and others authors such as Carr and Smeltzer (1997,

1999), Cox (1996), Cox and Lamming (1997), a segmented

list of the main elements of a supply strategy is provided.

This segmentation is based on the nature and scope of

supply decisions. Although all supply decisions are

important, some of them will be more critical to organisational performance, according to their impact on value

creation to customers.

A sound supply strategy should correspond to the goals

associated with higher-level strategies, as well in its

formulation, as in its implementation and deployment.

The proposed framework establishes three levels of action

for supply management and specific contributions to the

competitiveness of the firm (through strategic concern and

scope), to efficiency and effectiveness (through tactical and

operational concern and scope). Supply professionals are

then expected to ensure the realisation of the full potential

of supply ‘‘strategy’’ and ‘‘strategies’’ enhancing supply

management’s contribution, its functional consolidation as

well as the fulfilment of its specific strategic objectives.

6. Implications for supply managers

To reach integration and ensuring the right approach

throughout the challenging first stages of strategy-making,

supply managers should be aware of the risks involved. We

would like to emphasise three main implications for supply

managers, since they are not as obvious and easy to put

into practise, as one might be tempted to think:

(1) Find out corporate and/or business strategy and

understand it (them); you will be able to align the

supply ‘‘strategy’’ and demonstrate how supply management can respond to organisational goals and

objectives.

(2) Communicate business demands placed on supply by

the business strategy, as you understand them; you will

promote knowledge exchanges, thus creating a sense of

oneness that will empower the responsiveness of the

supply organisation to business changes.

(3) Systematically evaluate the effective contribution of the

supply ‘‘strategy’’ to corporate and/or business strategy; you will be aware of improvements to perform,

and are more likely to know when to make them.

7. Conclusions

The contribution of supply management and supply

‘‘strategy’’ to corporate strategy goals and objectives is no

longer a matter of discussion: it has become a reality.

Supply management is now called upon to develop sound

supply ‘‘strategies’’ intended to create value to customers

and bring out innovation. On the other hand, in a dynamic,

networked and changing business environment, supply

management has no choice but to be responsive, proactive

and innovative in building competitive capabilities.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

138

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

Table 3

A generic framework for a supply strategy

Firm strategy

Corporate/Business

Decisions/Objectives

Supply strategy

Function

Decisions/Objectives

Specific contribution/Performance indicators

Competitiveness (Business goals) What, Why?

Strategic concern and scope

Sourcing (global) decisions/strategies

Supplier selection strategies

Outsourcing decisions

Insourcing decisions

Partnerships and supply chain management

Technology adoption and investments

Competitive intelligence

Innovation and product life cycle management

Effective contribution to corporate value and goals;

definition and design of performance measurement

system (indicators)

Organisational (Means) How to?

Tactical concern and scope

Benchmarking and research

Processes and procedures definition

Sourcing (make-or-buy) analysis

Value-added analysis

Price determination

Supplier base management

Supplier certification programs

Supplier quality assurance programs

Project management

Budgeting and reporting

Insurances, legal aspects,

Contract management

Risk management

Operational concern and scope

Quality

Volume

Cost/Price

Service/delivery

Flexibility

Innovation

Centralisation/decentralisation/Outsourcing

purchasing or procurement

Results/performance (Effectiveness/efficiency)

Do it/Implementation

The main contribution of this article has been to make

explicit the meaning and relevance of ‘‘strategy’’ and

‘‘strategies’’ in supply management, to help the function in

fulfilling its role and accomplishing its objectives in the 21st

century environment. Moreover, the derivation of a

conceptual framework that exploits complementarity

among fundamental strategy-making approaches, and the

generic framework to identify critical strategic elements,

constitute basic tools to help formulate a supply strategy

and which should facilitate its implementation and its

deployment. Case studies and surveys to validate the

generic framework for supply strategy derived from

literature review and practical experiences are contemplated for future research.

References

Ambrosini, V., Bowman, C., 2003. Managerial consensus and corporate

strategy: why do executives agree or disagree about corporate strategy?

European Management Journal 21 (2), 213–221.

Andrews, K.R., 1971. The Concept of Corporate Strategy. Dow JonesIrwin, Homewood, IL.

Andrews, K.R., 1987. The Concept of Corporate Strategy, third ed. Irwin,

Homewood, IL.

Anonymous, 1995. A brief history of strategy. Harvard Business Review

73 (4), 121.

Anonymous, 1998. Supply strategy key to future growth at Ford.

Purchasing 124 (7), 83.

Ansoff, A., 1965. Corporate Strategy. McGraw Hill, New York.

Ansoff, A., 1969. Business Strategy. Selected Readings. Penguin Books,

Middlesex, England.

Ansoff, A., 1988. The New Corporate Strategy. Wiley, New York.

Arminas, D., 2003. More firms to outsource purchasing. Supply

Management 8 (23), 10.

Atkinson, P., 2004. Strategy: failing to plan is planning to fail. Management Services 48 (1), 14–20.

Beinhocker, E.D., Kaplan, S., 2002. Tired of strategic planning? The

McKinsey Quarterly 2, 48–57.

Burt, D., 1984. Proactive Procurement. The Key to Increased

Profits, Productivity, and Quality. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood

Cliffs, NJ.

Carr, A.S., Smeltzer, L.R., 1997. An empirically based operational

definition of strategic purchasing. European Journal of Purchasing &

Supply Management 3 (4), 199–207.

Carr, A.S., Smeltzer, L.R., 1999. The relationship of strategic purchasing

to supply chain management. European Journal of Purchasing &

Supply Management 5 (1), 43–51.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

Carter, P.L., Carter, J.R., Monczka, R.M., Slaight, T.H., Swan, A., 2000.

The future of purchasing and supply: a ten-year forecast. Journal of

Supply Chain Management 36 (1), 14–26.

Cavinato, J.L., 1999. Fitting purchasing to the five stages of strategic

management. European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management

5 (2), 75–83.

Corey, E.R., 1978a. Should companies centralize procurement? Harvard

Business Review Nov–Dec, 102–110.

Corey, E.R., 1978b. Procurement Management: Strategy, Organization,

and Decision-making. CBI Publishing Company, Inc., Boston.

Cousins, P.D., 2005. The alignment of appropriate firm and supply

strategies for competitive advantage. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 25 (5), 403–428.

Cox, A., 1996. Relational competence and strategic procurement management. European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 2 (1),

57–70.

Cox, A., Lamming, R., 1997. Managing supply in the firm of the

future. European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 3 (2),

53–62.

Croom, S.R., 2001. The dyadic capabilities concept: examining the process

of key supplier involvement in collaborative product development.

European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 7 (1), 29–37.

Doyle, M.F., 1990. Fundamentals of strategic supply management.

Purchasing World 32 (12), 40–41.

Ellram, L.M., Carr, A.S., 1994. Strategic purchasing: a history and review

of the literature. International Journal of Physical Distribution and

Materials Management 30 (2), 10–18.

Ellram, L.M., Zsidisin, G.A., Siferd, S.P., Stanly, M.J., 2002. The impact

of purchasing and supply management activities on corporate success.

Journal of Supply Chain Management 38 (1), 4–17.

Evered, R., 1983. So what is strategy? Long Range Planning 16 (3),

57–72.

Farmer, D., 1976. The role of procurement in corporate planning.

Purchasing and Supply, 44–45 (cited by Ramsay, 2001).

Frazelle, E.H., 1998. Develop world-class supply practices. Transportation & Distribution 39 (11), 45–49.

Govindarajan, V., 1989. Implementing competitive strategies at the

business level: implications of matching managers to strategies.

Strategic Management Journal 10 (3), 251–269.

Hadeler, B.J., Evans, J.R., 1994. Supply strategy: capturing the value.

Industrial Management 36 (4), 3–4.

Hamel, G., Prahalad, C.K., 1995. Thinking differently. Business Quarterly

59 (4), 22–35.

Hammonds, K.H., 2001. Michael Porter’s big ideas. Fast Company 44

(March), 150–155.

Harland, C.M., Lamming, R.C., Cousins, P.D., 1999. Developing the

concept of supply strategy. International Journal of Operations &

Production Management 19 (7), 650–673.

Hart, S.L., 1995. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Academy of

Management Review 20 (4), 966–1014.

Hayes, R.H., Wheelwright, S.C., 1984. Restoring Our Competitive Edge.

Competing Through Manufacturing. Wiley, New York.

Herbert, T.T., Deresky, H., 1987. Generic strategies: an empirical

investigation of typology validity and strategy content. Strategic

Management Journal 8 (2), 135–147.

Hill, T.J., 1985. Manufacturing Strategy. Macmillan, London.

Hill, T.J., 2000. Manufacturing Strategy: Text and Cases, third ed.

McGraw-Hill-Irwin, Boston.

Humphreys, P., McIvor, R., McAleer, E., 2000. European Journal of

Purchasing & Supply Management 6 (2), 85–93.

Kenny, G., 2003. Strategy, strategy burnout and how to avoid it. New

Zealand Management August, 43.

Knights, D., Mueller, F., 2004. Strategy as a ‘project’: overcoming

dualisms in the strategy debate. European Management Review 1 (1),

55–61.

Leenders, M.R., Johnson, P.F., Flynn, A.E., Fearon, H.E., 2005.

Purchasing and supply management, 13th ed. McGraw-Hill-Irwin,

Boston.

139

Masch, V.A., 2004. Return to the ‘‘natural’’ process of decision-making

leads to good strategies. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 14 (4),

431.

McCarthy, B., 2003. Strategy is personality-driven, strategy is crisisdriven: insights from entrepreneurial firms. Management Decision 41

(4), 327–339.

Mintzberg, H., 1987. The strategy concept I: five Ps for strategy.

California Management Review 30 (1), 11–24.

Mintzberg, H., 1994a. The Fall and Rise of Strategic Planning. The Free

Press, New York.

Mintzberg, H., 1994b. The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harvard

Business Review 72 (1), 107–115.

Mintzberg, H., 1999. Reflecting on the strategy process. Sloan Management Review 40 (3), 21–30.

Monczka, R.M., Trent, R.J., Callahan, T.J., 1993. Supply base strategies

to maximize supplier performance. International Journal of Physical

Distribution & Logistics Management 23 (4), 42–54.

Morgan, J.P., Monczka, R.M., 2003. Why supply management must be

strategic. Purchasing 132 (7), 42–45.

Norton, D.P., 2002. Managing strategy is managing change. Balanced

Scorecard Report 4 (1), 1–5.

Norton, D.P., Russell, R.H., 2004. Best practices in managing the

execution of strategy. Balanced Scorecard Report 6 (4), 3–10.

Paliwoda, S.J., Bonaccorsi, A.J., 1994. Trends in procurement strategies

within the European aircraft industry. Industrial Marketing Management 23 (3), 230–244.

Parnell, J.A., Lester, D.L., 2003. Towards a philosophy of strategy:

reassessing five critical dilemmas in strategy formulation and change.

Strategic Change 12 (6), 291–303.

Porter, M., 1990. The Competitive Advantage of Nations. The Free Press,

New York.

Porter, M., 1991. Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strategic

Management Journal 12 (Special Issue), 95–117.

Porter, M., 1996. What is strategy? Harvard Business Review 74 (6),

61–77.

Rajagopal, S., Bernard, K.N., 1993. Strategic procurement and competitive advantage. International Journal of Purchasing and Materials

Management 29 (4), 13–20.

Ramsay, J., 2001. The resource based perspective, rents, and purchasing’s

contribution to sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Supply

Chain Management 37 (3), 38–47.

Rink, D.R., Fox, H.W., 2003. Using the product life cycle concept to

formulate actionable purchasing strategies. Singapore Management

Review 25 (2), 73–89.

Rylander, A., Peppard, J., 2003. From implementing strategy to

embodying strategy: linking strategy, identity and intellectual capital.

Journal of Intellectual Capital 4 (3), 316–331.

Saarinen, T., Vepsalainen, A.P.J., 1994. Procurement strategies for

information systems. Journal of Management Information Systems

11 (2), 187–206.

Skinner, W., 1969. Manufacturing—missing link in corporate strategy.

Harvard Business Review 1969 (May–June), 136–145.

Skinner, W., 1978. Manufacturing in the Corporate Strategy. Wiley, New

York.

Spekman, R.E., 1985. Competitive procurement strategies: building

strength and reducing vulnerability. Long Range Planning 18 (1),

94–99.

Starr, M.K., 1984. Global production and operations strategy. Columbia

Journal of World Business 19 (4), 17–23.

Sutton, B., 1989. Procurement and its role in corporate strategy: an

overview of the wine and spirit industry. International Marketing

Review 6 (2), 49–59.

Turner, I., 1997. Strategy and organization: strategy and unpredictable

environments. Manager Update 8 (3), 1–9.

Voss, C.A., 1995. Alternative paradigms for manufacturing strategy.

International Journal of Operations & Production Management 15 (4),

5–16.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

140

J. Nollet et al. / Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 11 (2005) 129–140

Watts, C.A., Kim, K.Y., Hahn, C.K., 1992. Linking purchasing to

corporate competitive strategy. International Journal of Purchasing

and Materials Management 28 (4), 2–8.

White, M.C., Smith, M., Barnett, T., 1994. Strategic inertia: the enduring

impact of CEO specialization and strategy on following strategies.

Journal of Business Research 31 (1), 11–22.

White, J.C., Conant, J., Echambadi, R., 2003. Marketing strategy

development styles, implementation capability, and firm performance:

investigating the curvilinear impact of multiple strategy-making styles.

Marketing Letters 14 (2), 111–124.

Wind, Y., Robertson, T.S., 1983. Marketing strategy: new directions for

theory and research. Journal of Marketing 47 (2), 12–25.