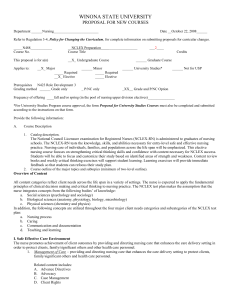

Academic and Nonacademic Predictors of

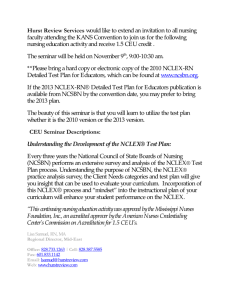

advertisement