VIEW PDF

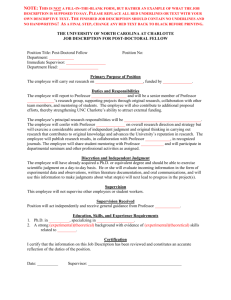

advertisement