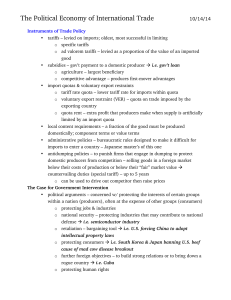

The interface between foreign direct investment and the environment

advertisement