Managing Codified Knowledge

45

Michael H. Zack

A framework for

aligniHfi organizational and technical

resources and

capabilities to

leverage explicit

knowledge and

expertise.

Michael H.Zack is the

Patrick Rand Helen C.Wilsh

Research Professor, Colleiie

of Business Administratio I.

Northeastern Universitv.

Sloan Management Review

Summer 1911

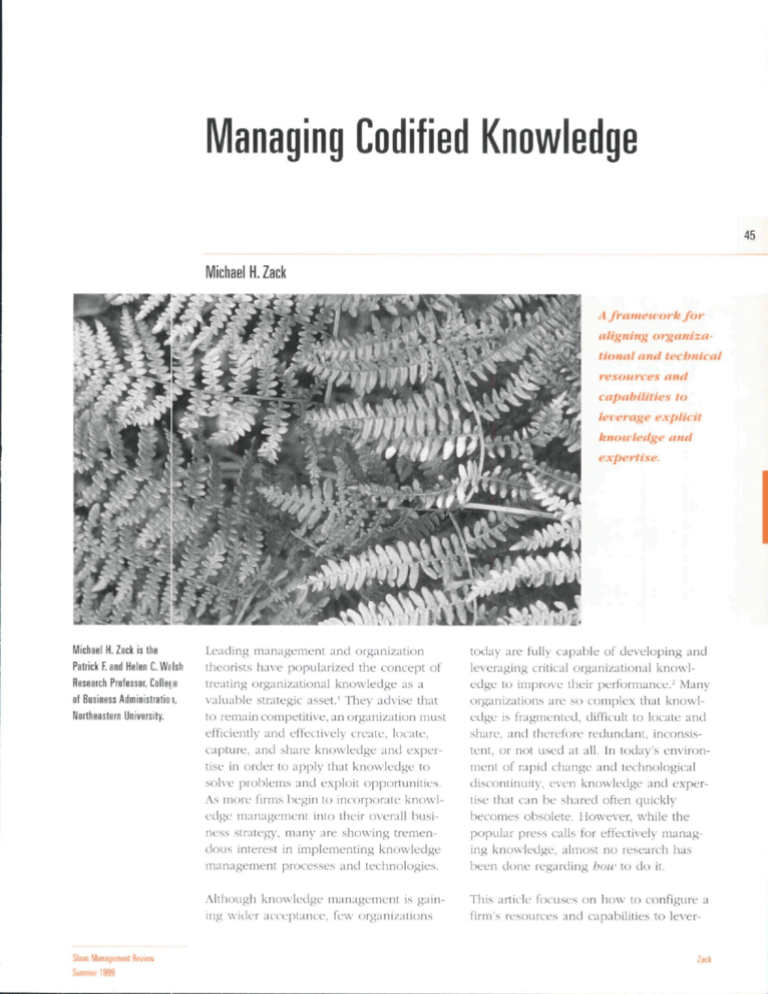

Leading iiianagcmcnt and organization

theorists have popularized the concept of

treating organizational knowledge as a

\'aluaf)le strategic asset.' They advise that

to remain competitive, an organization must

efficiently and effectively create, locale,

capture, and share knowledge and expertise in carder to appiy that knowledge to

solve prol.")lems and exploit opportunities.

As more firms liegin to incorporate knowledge management into their overall business strategy, many are showing tremendous interest in implementing knowledge

management processes and technologies.

today are fully capable of developing and

leveraging critical organizational knowledge to improve their performance.- Many

organizations are so complex that knowledge is fragmented, difficult to locate and

share, and therefore redundant, inconsistent, or not used at all. In today'-s environment of rapid change and technological

discontinuity, even knovv'ledge and expertise that can be shared often quickly

becomes obsolete. However, while the

popular press calls for effectively managing knowledge, almost no research has

been done regarding bow to do it.

Although knowledge management is gaining wider accei;>Uince, few organizations

This article focuses on how to configure a

firm's resources and capabilities to lever-

Zacli

age its codified knowledge. I refer to this broadly as

a kftowk'dge maucigcnieiit drchitccture. I based this

framework on research that was nintivatcd by several

46

• What are the characteristics (jf explicitk' c

knowledge and how sh(uild (jigani/ali()ns ihink

about nutnaging ii?

• What role should information technolog\' play?

• How are organizational capabilities and inlormiilion

technology best integrated and ajiplicd tc) man^iging

knowledge?

• What lessons ha\'e companies learnetl in these

endea\'ors?

To address these questions. I first describe the cliaracteristics of explicit knowledge and its relationship

to competitive advantage. Building on research and

knowledge aboiil the design of intornuiiion prodiicis,'

I describe an architecture for manjgiiig explicit knowledge. I use that framework lo deii\e two fLinclamentai and complementary' appi'oaches, each of whit, h is

illustrated hy a case study. I conLkide wilh .1 sumnuivw of kev issues and the less(jns leained.

What Is Knowledge?

Knowledge is commonly distinguished from data antl

information. Data represent obseivations or fads out

of context that are, therefore, not tlirectly nieuninglLil.

Information results from placing data within some

meaningful context, often in the form of a message.

Knowledge is that which we come to believe and

value on the basis of the meaninglully oigani/etl ucctinuilation of inlbrmation (mes,sages) throLigh expetience, communication, oi' infeience,' Kntiwledge can

be viewed both as a thinf> to be stored and manipulated and as a process of simultaneously knowing antl

acting — that is. applying expertise,' As a pi^actical

matter, organizations WK^^^d to manage kncnvledge both

as object (ind process.

Knowledge can be tacil or explicit.' Tacit knowledge

is subconsciously understood and applied, difficult to

articLilate, developed from tlirect experience and

aclion, and usually shared thi'ough highly interactive

conversation, stoiytelling. and shared experience. In

contrast, explicit knowledge is more [precisely antl

formally articulated, allhoiigh remo\ed hom the origi

nal context of creation or use (e.g.. an abstr;ict mathematical formula derived from physical experiments

or a training manual tlescribing lu>\\ (o close LI sale).

Zack

Explicit knowledge is more precisely

and formally articulated, although

removed from the original context of

creation or use.

K\j)ii<,it knowk'dge pl.iyN .in increasingK laiger role

in oigani/ations, and niLiny consider it the most

important factor ol production in the knowledge

economy, (hnagine an organization without procedure

manuals, product literature, or ct>mputer software.)

Knowledge may be of se\'eral types,' all of which can

be made explicil:

• l)cclarati\e knowleclge is about (lescnhiii,i> something, A shared, explicil understanding ot contepls.

eategoiies, and descriptors lays the foundation for

effective comnuinicaiion and knowledge sharing in

organi/ati(jns,

• Procedural know letlge is about hatf something

occurs or is [lerfoi'med. Shared explicit prcKedmal

knowledge LIVN a toiiiKlation for elTitientK coordinated aclion in oiganizations,

• Causal knowledge is about icby something occLirs.

Shared explicit caLisal knowledge, often in the form

of organi/alional ,^tories, enables orgLinizalions to

cooixlinate sirak'gy for achieving goals or outcomes,

Knowletlgc also may ratige Irom the general to the

specilic:"

• General know ietlge iN broatl, olten publii-'K available, and inde[")endent of particular e\ent>. Because

ihe ctintext of general knowledge is cotiimonly

shared, firms can more easily and meaningfully codify

antl exchange it — especially among different knowletlge or practice comiiumities,

• SjX'eific knowletlge. in ct)ntrast. is context-specific.

c:otlifying sjK'cific knowledge so that it is meaningiul

across an organi/alion ret|tiires ihat a firm descrilie its

conicxt Lilong wiili the tocLtl knowletlge. This, iti Uirn.

requires explicitly dehning contextual categories and

relationshi|)s that are meaningfLil aci'oss knowletlge

communities. To ,>ee how tlifficiili (antl i[n|)ortant)

this may be. ask people Iroiii tlittereiit [larts o! your

oigani/ation to tiefine a customer, an order, or even

your major lines of business, antl oiiseive how much

the respon.s(.-,s tlilicr,"

Sloan Management Review

Summer 1999

Explicating Knowledge

Ht'tc-ctivc pcrtoi'mtncc- antl growth in knowledgeiniL'nsivc organizations rc'tjuircs integrating and sharing highK' clistribiitt'cl knowledge." Howt'\x-r. apjiropriatcl\- c.Kplitatii g tacit knowledge so it can be vtTiciently and mcaningt'Lilly shared and rcapplied, especially outside the originating community, is one of

the least understood aspects of knowledge management, ^'et organisations must not shy away from

attempting to explicate, share, and leverage tacit, spccific knowledge. This sugge.sts a more fundamental

challenge, namel'/, determining which knowledge an

organization shoi.id make explicit and which \l

shoukl lea\'e tacil — a balance that can atfcct competitive performance.

Knowledge may :)e inherently tacit or seem tacit

betause no one has yet articulated it, usually because

of sociai constraints," Articulating particular types of

knowledge may not be cullurally legitimate — that is,

challenging wliat the firm knows may not be socially

or pcjlitically correct, or the organization may be

unable to see be;,'onci its habits and customary practices. And, of course, making private knowledge publicly acce.ssible n ay result in power redistribution ihal

certain organizational cultures may .strongly resist. In

addition, intelleclual constraints — that is, the lack oi

a formal language' or model for articulating tacit

knowledge — m.iy impede efforts to make it explicit.

When one compares the potential explicability of a

body of knowlecge to whether a firm has articulated

that knowledge, four outcomes are possible (see

Figure I). If left anarticulated, potenlially explicable

knowledge represents a lost opportLinity to efficiently

share and. thus, everage that knowledge, A competitor, by articLilaiing a similar body of knowledge so it

can he rcnitinely integrated and applied, ma\- gain a

competitive advantage in the marketplace. However,

attempting lo ma ie inherently inarticulable knov\ledge

explicit may resull in losing the essence of that knowledge, causing performance to suffer. Determining

when to make articulable knowledge explicit (i.e.,

exploiting an op :>ortunity) and when to leave inarticulable knowletlgj in its "nati\e" form (res[")ecting both

the inherent strengths and limits of tacit knowledge)

is central to man;,ging an appropriate balance between

tacit and explicit knowledge.

Organizations ofien do not challenge the way they

store, treat, cjr pass on knowledge, which may result

Sloan Manayement Review

Summer 1999

in managers blindly accepting the apparent tacitness

of some t\'pes of knowledge, Mrs, Fields Original

Cookies de\eloped process knowledge <i,e,, cookie

baking) to an ex]')licab!e le\el and articulated the

process in recipes that resull in cookies of consistently high quality throughout the franchise network.'Ray Kroc. founder of McDonald s. gaini'd tremendous

leverage in articulating and routinizing the process of

hamburger making to produce a consistent (if not

gourmet) level of quality. But when imagination and

flexibiliiy are iniportani, knowledge routinization may

be inappropriate. It is the manager's responsibility to

know the difference.

Thus far. I have detined explicit knowledge, discussed

some of its characteristics, and made a case fbr explicating knowledge, AlthoLigh explicil knowledge repre,sents only part of an organization's intellectual

landscape, it is crucial in a firm's overall knovs'ledge

strategy. Next, I describe the frameworks and architectures needed tor managing explicit kntjwleclge.

Knowledge Management Architecture

The management of explicit knowledge utilizes four

primary resources (see /-'ignre 2):'''

• Repositories of explicit knov\iedge.

• Refineries for accumulating, refining, managing,

and distributing the knowieelge,

• Organization roles to execute and manage ihe

refining process,

• Information technologies to sLipport the repositories and processes.

Knowledge Repository

Design of a knowledge repositoiy reilects two basic

Figute 1

Outcomes for Explicating Knowledge

S/ . Exploited

' ":'••: opportunity

Inappropriately

explicated

Yes

Lost

opportunity

Appropriately

unexplicated

No

Explicated^

Zack

47

Figure 2

The Architecture of Information Products

Knowledge Platform

Knowledge Views

Repository

• Structure

• Content

• Content

• Format

• Presentation context

48

Storage

Acquisition

Refinement

Distribution

Presentation

Retrieval

Refinery

Technology Infrastructure

Organizational Infrastructure

Source Adapted from M H Meyer and M H Zack, "Thfi Design •! Infaimalion Products," Sloan MumigQuieni Rmew. voljme 37, Spring 1996, p 47

Figure 3

Composite Knowledge Repositories

Module A

Module B

Composite Platform

Module C

components ol knowledge as an object: slrucliire

and coHli'iit.^' Knowledge structures provide the context for interpreting act unuilaled content. It ;i re[io,sitoiT were conceived as a "knowledge plattbrni." a

firm coLild deri\'c many views of the content from a

particular repositt>ry structure. Hach view of the

repository may differ on the basis of its content, foi"nuit, and presentation context." A liigli degree u\

\ie\ving tlexibilit)' enables users to cK'namicalK' altei'

Lincl interactively combine views to nxjre easily apply

the knowledge lo new contexts and circumstances.

Knowledge-as-ob|ect becomes knovvledge-as-[:irocess.

Zack

Module D

The basic .structLiral element is the ki/oiiiedge iiiiil. a

formally defined, atomic packet of knowledge content

thai tan be laiieled, iiKiexed. sioretl. retrieveti. and

manipulated. The format, size, and content of knowledge units may vary, depending on the type of

explicit knowledge being stored and the context of

its Lise. The rejiosiion- structtire also includes stheme.s

toi' linking and cross-referencing knowledge units.

These links may represent conce|5tual associations,

ordei'ed se(.|Lientes. cau.salily, or other relationships.

de(ieiiding on the type of knowledge being stored.

Sloan Managemenl fleview

Suinmei 1999

To rcflcci a full ningc of explicit organi/ational knowleclge, firms nuist ,stri\t.' to record in iheir repositories:

• Meaningful concepts. caleg'""i'-'s- ^mtl tleliiiilions

(tleclaiati\e knowledge).

• Processes, actions, and sec]uence.s of e\'ents (procedural knowledge).

• Rationale for aLlions or conclusions (Lausal knowledge).

• CireLiinstances and intentions ot knowledge de\elopnient and app ieation (specific coniextiial knowledge).

• LinkLiges amorg the \'arioLis types ol knowledge.

Such a icposiiop. when inde,\e(.l using appropriate

concepts and categories, can i^rovide the organi/aiion

with nieaningtul access to its content. The repositoiy

should accoiiiincdate changes or additions t(j the

tii'iii's knowledge (e.g.. by linking annotations), as

suhset|Lienl aiithoi.s and creators ada[:)t the knowledge

for use in acidilional conte,\ts.

A knowletlge phtforiii nia\ consist ot se\'eral repositories, eaeh with a structure appropriate lo a particLilar type of knowledge or eonient. The.se repositories

may lie logically linked to form a composite or "virtLial" lepositoi"}'. the content of each jiroviding context for interpret ng the contenl ot the others (sec

Figure J). Tor e>.am[')le. [irodtict literature, best-sales

practices, and c( nipetitoi' intelligence for a particular

market iiiighl be stored separ^itely luit viewed as

thoLigh containet.l in one repositon.

Knowledge Refinery

The refiner)- rep e.sents the process for creating and

distrihuting the knowledge contained in a repository'.

This prtK'ess includes five stages (see Figure 2>:

An organization either creates information and knowledge or acc|Liires it frotn variotis internal antl exlernal sources.

• RcfineDiciil. l^jfore adtling cajitured knowleclge to

a repositoi-)-. an organization suhjecls ii {o valueadding processe-i (refining), such as cleansing, labeling, indexing, si'iting, abstracting, suindardi/ing. integrating, ancl ree;,tegorizing.

• Storage coid rclrieval. This stage bridges upstream

repositoiy creati'jn and downstream knowledge distribution,

• Distrihiitioii. This stage comprises the mechanisms

an organization uses to make repositoty content

accessible.

• I'lvsciiliilioii. The eontext in which an organization

Sloan Management Review

Slimmer 19S9

u.ses knowledge pervasively influences its value.

Firtns mu.st develop capabilities that enable flexibility

in arranging, selecting, ancl integrating knowledge

content,

.\e(.[Liisition. refinement, antl storage create and update

the knowledge platfoini, wiiereas retriexal. distribtition, and presentation deri\e \arious \-iews of that

knowledge.

49

Knowledge Management Roles

Knowletlge management programs often overetnphasize information technology at the expense of welltlefined knowledge management roles and responsibilities. Traditional organizational roles typically do

not address knowledge management or the crossfunctional. cr(.)ss-organizationai process that a firm

uses to create, share, and apply ktiowiedge, I pi'esent

an architecture that sLiggesis a set ot organizational

roles a firm should define explicitly. First, .some organizations assign a chief knowledge officer to comprehensi\'el\' handle knowledge ntanagement as a crossorganizational process. This person is responsible tor

the organization's knowledge management arehitecture, .Many organizations also cltister those responsible

tor know ledge management into knowledge or expertise centers, each being resj">onsible tor a particular

body of knowledge. Their responsibilities typically

include championing knowledge management, educating the organization, mapping knowledge, and

integrating the organizational and technological

resoLirces critical to the knowledge management

arciiiteciure. In adtliiion, fiinis must assign explicit

responsibility for each stage of the refineiy and their

interfaces, A.ssigning responsibility for the seamle.ss

movement of knowledge from acquisition through

use, as well as the interfaces between the,se stages,

helps to enstirc that knowledge repositories will be

tneaningfully created and ettecti\-ely used.

Role of Information Technologies

The information technology infrastructure provides a

.seamless "pipeline" for the flow of explicit knowledge through the t"\w stages ol the retining process

to etiahie:

• t^apturing knowledge,

• Defining, sttiring, categorizing, indexing, and linking digital objects that correspond to knowledge units.

• Searching for ("pulling") and subscribing to ("pushing") rele\'ant content.

• Presenting content with Nufticieni flexibility to ren-

Zack

Effective use of information technology

to communicate knowledge requires that

an organization share an interpretive

context.

50

dcr it liK-aningRil and aj;)plical>lc across mulUplc conttfxis (jl" ust'.

U.sing information tcchnologiL's — for cxaniplf. [hf

World Widf Web and groupwarc — a firm can Iniild

a niLillimcdia repository for ricli, explicit knowledge.

Organizations capture and sttjre units of knowledge

in forn^s that assign varioLis labels, categories, and

indexes to tlie inpLit. A flexible structure create.s

knowledge units, indexed, and linked by categories.

thar reflect the structure of the contextual knowledge

and the content of the organization's factual knowledge, displayed as flexible subsets \ ia dynamically

customizable views.

Effective use of inttjrmation technology to communicate knowledge ret[Liires that an organization share

an interpretive context. When communicators share

similar knowledge, liackground, and experience, they

can more effectively communicate knowledge via

electronically mediated channels.'" Fcjr example, by

means of a central electronic repositoiy. an organization can disseminate explicit, factual knowledge

within a stable community having a high degree of

shared contextual knowledge. However, when communicators share an interpretive context only to a

moderate degree, when they exchange knowledge

that is less explicit, oi' when a comnumity is kiosely

affiliated, more interactive modes — such as e-mail or

discussion databases — are appropriate. When ctintext

is not well shared and knowletlge is primarily tacit,

firms can best support comnumication and narrated

experience with the richest and most interactive

modes, such as videoconferencing or face-to-face

conversation.

Classifying Knowledge Management

Applications

On the basis of this concept of knowledge management architecture, a firm can .segment knowledge

processing into two broad classes: integraHre and

iuteractire. each addressing tlifferent knowletlge

Zack

management objectives. Together, these approaciies

provide a broad set of knowledge-processing capabiiities. They support well-structured repositories for

managing explicit knowledge, while enabling interaction to integrate tacit knowledge.

Integrative Applications

Jiiiegralire applicaluDis exhibit a sequential flow of

explicit kntjwiedge into and out of a repository.

Producers and consumers interact with the repositoiy

rather than with each other directly. The repository'

becomes the primary medium for knowledge

exchange, providing a place for members of a knowledge community to contribute their knowledge and

views. The primaiy focus tends lo be on the repository and the explicit knowledge it contains, rather ihan

on the contributors, users, or the tacit knowledge

they may hold.

Integrative applications vary in the extent to which

knowledge producers and consumers come from the

saine knowledge community. At one extreme, which

I label electronicpublisbing, the consumers (readers)

neither directly engage in the same work nor belong

to the same practice community as the producers

(authors). Once published, the content tends to be

.stable, and the few updates required usually originate

with the authors. The consumer accepts the content

as is. and active user feedback or modification is not

anticipated (although it ct)uld be allowed). For example, the organization may produce a newsletter, or its

human resources tiepaitment may publish its policies

or a tlirector)- of employee skills and experience.

At the other extreme, the producers and consumers

are members of the same practice community or

organizational unit. While still exhibiting a sequential

flow, the repositoiy provides a means to integrate

antl build on their collective knowledge, I label this

an i)Uegmtcd kitouiedge base. A best-practices database is the most common example t)f this type of

applicatioii. Practices are ctjllcctetl, integrated, and

shared amc^ng people confronting similar problems.

Regarding lhe organizational roles for managing integrative applications, acquisition requires knowledge

creators, finders, and collectors. Capturing orally conveyed knowledge requires interviewers and transcribers. Documenting observed experiences requires

organizational "reporters." Identifying and interpreting

deeply held cultural and social knowledge may

ie(]Liire (.orpoiaie anthropologists. Refining requires

Sloan Management Review

Summef 1999

analysts, interprelers. abstractors, classitieis. et

aiKl integrators. /•. librarian or "kinjwledge curator'

iiiList manage the repository. Others iniisi laki'

i'cs[ionsibili[y foi' atccss. tlistribiition, antl prL'si'iita

lion. 1-inaily, orgiinization.s may need peo[)le to tiain

Liseis to critically inierpret, e\akiate, and atla])t

knowletlge lo ne^- contexts.

Interactive Applications

hilcniilitv

iil)j>liL!ilii>iis

f o i l i.s p r i i n a i i h o n

sLipjxntiiig

intcraclion a m o i v ; those p e o p l e wilh laui k n o w l e d g e .

in '.•otiirast lo integrative applications, the repository

is a by-piotlLKt of interaction a n d collaboration rather

than the piimary f o t u s ol lhe applK;iti(in. Its

is tlynamic antl e m e r g e n t .

lmuiatti\e applic.itions \ ar\ atcortlint^ to ihe e\])eitisi,le\el of jii'otluceis and consumers and the degrcL' ol

sti'uclure imc)osetl on their iuli-iaciiou. Wliun lormal

training or know edge transter is the objecii\f. the

iniL'raction tentls :o be primarily between iiistruitoi A\\'-\

stLitient (or ex]ierl atui no\ice) Linti sirutturetl aioimd

a tiistrele [:>roble n. assignment, oi le.sson pi.in.' I

lefer to the.se applications as cii.^l)il)iiU'i( leciniiiiii,.

Highly interactive forums support ongoing, collahorative discussions among the

producers and consumers as one group.

ill loiilrasl. iuteratlion aniong those p<,-i ton

mon practices or lask.s tentls lo be inoie ati IKK t

emergent, I broa'.lly refei" lo these a|>plitation.s as

for/inis. Ihey may take the form ot a knn\'.letlge

kerage — an cle:troiiit tliscussion sjiacf where

ple may eithei' search tof knowledge (e.g.. "DOL

anyone know, . .") or atKertise their expertise.

Highly iiiterai.ti\i' loiLims sup|>or! ongoiiig.

ti\e tliscu.ssioiis Limoiig the [^lotkiteis and c

Lis one gi'oup. c<.ntinually respoiitiing tt) antl buiklini;

on CLich indi\ itlual's additions to lhe tlistussion, Thtflow continually loops back tioiii pifseulation to

acc|Liisition. W'itli the appix>priak' siiiuunini; antl

intlcxiiig of lhe contenl. a knowledge ie[">ository

emerges. A stantkiid categorization scheme indexes

contributions .so the tiiin lan u'appK ih.ii kno\^lftlge

acio.ss the

Intc'iac ti\ e applicalion> play ;i major lole in sL

intt'grati\f afifilit alions." h'oi' e \ a m | ) l e . a torum ina\

be liiikcti to an electi<)nic-]iLiblisliing a|ic>lication so

that ftliiors t a n tli.scuss lhe <.|uality ot the contributums Ol |)io\itk' a plate tor reatlci.s to w:\ui to antl

tlistuss the pLiblitahon. Besi-jiraclice tiatabases typitally rec|uiiv some tlegree of lorLiiii interaction, so that

ihose attempting to atlojit a jiractice have an opporuiniiN to tlistiiss its [eap|)litLition with its (I'eaiors.

Kfgaitling the txgani/atioiial roles lor managing iiiterj c t i \ e a|)plicalion.s. acc|uisitiou iet|Liiies letriiiters antl

tacililators to eticoLitage antl manage panicipation in

forLiins so thai those with app[o[Mi.iiL- exjiertise touliibulf. Till' I ommiiiiiLators otteii retine, stiLittme, aiKJ

index iht- lonleiil, using gLiitlflines antl talegoiies

built into lhe .ip[)li<-aiion antl suc)[)leiucntf(.t liy a

tonleu'iUL' niotleiatoi. AssLuing lhe (|U.ilii\ ol the

knowledge may leqiiiie quality-assLiraiKe per.sonilel,

s u i h as subiett-malter experis anti reputation brokers.

Usually a tonfereiue nioderaioi niaiuigcs a tonlerfiice

it'|>o,siio[y throiighoLit iis Mk' t ycle Iniiially. others may

ncetl lo wink wilh u^eis until they are comlortable

wiili gLiiniug a t t e s s lo and Lisiiig the ap|)lication.

Two Case Studies

I j>iesenl tv\o cases studies of m a n a g i n g explic it know 1etlge. (JiK* is :in f\ain[ile ol AU i[|lc*giali\ C Lire hitetlLire

lor llif elt-ctionic ]Uiblishing ol knowletlge gleauctl

b\ iiiciustiA resuarth a n a K s t s . ' ' T h e si,-(.ond illu.siiales

ihf f l t e c t i \ e use ot an inlcraclixL- aichitecture loi' distLission ioi'ums lo ,sup|iori scr\ icing c iistonifrs.-"

Integrative Architecture

IVchnology Kcsearch lnc\ CIKI)' is A leading inlt-rnalional |)io\idc-r of market iiiioimaiioii anci incUistry

.iiiaKsis lo liitoiinaiion icchnology \eiitlors a n d puri hasc-is I Kl fiii|)lo\s m o r e than M)0 analysts ;inti

annualK pubiishcs iiioie lliail IS.lHKl iivsiMich reports

thai a d d r e s s m o r e than htly disiiiKt sLibjett a r e a s

(called r e s e a u h |)rog;.iin.s). (^leu l-'ii>ii/e 4 tor TKI's

k n o w l e d g e nian.igeinenl arc hilet Uire.)

The' on-lint- k i i o w l e d g e repository c o m p r i s e s a standard sfl ot kiiov^lctlge unils consisting ot lhe e x e c u t i \ e sumiiijiic's. abstracts, main te.xt, gia])liics, tables,

antl charts trom 'rKl research ie|>orls. T h e c-omj)aiiy

uptlaies its leseaich ie|x>rts contiauoiisly, s o lhe

repo.siiois is, in iliis sense, dynamic. K n o w l e d g e Linits

aic iiitlfxctl .mtl luikett for flexible access, autt LISCIS

iiia\

Mi.|iii.nlially

navigjk-

l i o m

o ii c u i u l

l o llit-

iiexi

within a rc|iori, access siuiilai units acro.s.s leporis

(f.g., exfculi\t.' summaries only), or access [iLirticular

Linils diiecth. This sumciardi/ation enables 'IKt lo

Zach

Summet 1939

51

Figure 4

TRl Knowledge Management Architecture

• Reports

• Newsletters

• Bulletins

Repository of Research

Results

Acquire

Telephone calls and

surveys

Store

Refine

Distribute

Present

Analyze, interpret,

and report

T

52

Edit and format

Decompose into

knowledge units,

index and link units

PCs and desktop software

Index and link

knowledge units

Post on-line vta

Web-enabled Lotus

Notes'"'

Lotus Notes'"

Information systems

group

integrate analysts" explicated knowledge across

research programs for mcta-analysis, creating new

knowledge not possessed Iw any single analyst. As

technology changes, new re.search areas emerge that

cut across TRI's traditional research programs and

internal organip^ational boundaries. Building repositories based on a flexible yet standard structure enables

TRl to respcjnd by integrating those repositories into

composite platforms to support virtual research programs. From its repcsilories, TRl derives standard

monthly reports and more frequenl ad hoc bulletins

tor each research program frt^m several electronic

formats (Web. CD. fax. e-mail).

TRl s refiner}' encompasses two stages; analysis and

publishing. Analysis involves ctillecting, evaluating,

and interpreting market information, and reporting

the results. The analysts' tacit knowledge of their particular industry is applied to this information to prodtice an explicitly reported interpretation. The

process is similar to investigative reporting, in that

analysts try to get "the story behind the numbers."

In the publishing stage, editors convert analy.sts'

reports to a standard format and decompose them

into knowledge units, assigning standard document

identifiers and keywords and creating links among

knowledge units. While perhaps less efficient than

having all analysts initially write to a standard format.

TRI's approach preserves the analysts" autonomy and

creative, entrepreneurial spirit. TRl manages this

trade-off to foster a balance between the efficiency

Zack

Interactive selection

of knowledge units

Web browser or

Lotus Notes'" client

Customers

and speed of knowledge management and knowledge-worker morale, commitment, and performance

quality. TRl distributes on-line documents primarily

\'ia Web-enabled Lotus Notes.™

Implementing this new architecture has

been as much an organizational and

social intervention as a technical one.

TRI's experiences illustrate how digitizing content

alone is not adequate to exploit the opportunities for

flexibility and innovation in the design and delivery

of explicit knowledge. Digitized documents must be

structured as knowledge units within a modular and

flexible repository from which multiple knowledge

views can be rapidly and efficiently created as newuser needs arise in new contexts, ln addition, a

robust, seamless, and scalal)!e technology infrastructure is key to enabling the flexibility required for an

integrative knowledge management refineiy. It provides a multitude of user-defined views of rich, multimedia documents, embeds hyperlinks, and provides

an efficient yet flexible distribution channel.

Implementing this new architecture has been as

much an organizational and social intervention as a

technical one. TRl assigned and then trained people

to perform new roles to shejiherd the nujvement of

Sloan Managemenl Review

Summer }999

knowledge from taw to useable jiroduct; this humanresource investment was instrumental in the company's success. However, the exi.sting roles and responsibilities of'I'RI analysts, editors, antl IT pioicssionals

have changed. The mo\e to institute process and

content standard,'- reduced the le\ el of analyst autonomy antl discretion in rcgaixi to writing format antl

style, placing many decisions in the hands of editors

and production s:aff. Ultimately, success in electronic

pLiblishing was b.ised at least as much on effectively

managing (>rgani/,ational change as on inipleinenttiig

a sound product architecture and electronicpublishing tethnok^gy.

Interactive Archiiecture

Buckman l.aboraiories (BL), a $300 millit)n internatitjnal specialty chemicals company with more than

1.200 employees (called associates) operating in more

than HO ct)Linu-ies. is a recognized leader in knowletlge management.-The basis for competititin in BL's industiy has changed

from merely selliig products to solving customers'

chemical-treatmeit problems, lliis requires not only

knowledge of products and their underlying chemistiy. bLit Lilso knowletlge of how to apply them in

varit)us contexts. While many BL associates have college degrees in chemistr>' and related fields, selling

antl a|")p!ying BI. products requires practical field

experience in sohing cuslomcr [problems. This

knowletige is tacit, residing primarily wilh the field

asstK'intcs scatter Jt! worltiwide, I'ieltl-based knowledge is complex in that it has lo account for, often

subconsciously, many interacting variables and can

be specific tt) a ^.eographical region, a mill, or even a

particular machire. It is tiynamic, emergent, antl continually evoking. BL managemenl belic\cs that in this

type of competitive environment, strategic advantage

results primarily Vom applying the mc^st recent practical knowledge and experience of all associates to

each customer problem.

To acctjmplish tlis. Hob Muckman, chairman ot BL

Holdings (the BL parent company), en\isioned an online knowledge management capability' that BL im|")lemented as K'.Vetix," The Buckman Knowledge

Network. It was founded on several key principles:

• Direct exchanj:;c of knowledge among employees,

• LJniversal, unconstrained ability to contribute to

and gain acce,ss lo the firm's knowledge without

regard for time /one. physical location, language, or

Sloan Management Review

Summei 1999

level of computer proficiency.

• Preser\-ation of ctjnversations, interactions, ct)ntributit)ns, and exchanges.

• Fasy accessibility — that is, searchable by all BL

a,ss(x iates.

BL has placcti much of its explicit knowledge about

customers, products, and technologies intt) t)n-line

electronic repositories comprising a set of integrative

knowledge management applications. However, BL

has progres,setl well beyond integrative knowletlge

management. Its on-line interactive Tech Foaim supports the core of BL knowledge strategy (see Figure

5). Any associate can use Tech Forum to locate, capture, tlistribute, sliare, antl integrate llie practical,

applied knowledge and experience of all other BL

associates in support of the custtimer.-^ The forum

uses a stantlartl structure; comments arc "threaded" in

conversatit)nal sequence and indexed by topic, author,

and tlate. The content typically comprises questions,

responses, and field obseivations.

Weil defined and specifically assigned, knowledge

managemenl roles at BL are of two broad classes:

those that facilitate the tlirect and emergent exchange

of knowletlge through the lorLim (ihe interacti\'e

aspect of the architecture) and tht)se that support

refining and archiving the record of those exchanges

for future use (the integrative aspect). BL has successfully iniegrated the two in terms (}f organization

struclLire antl knowledge How.

Iil. organizes several knowledge management roles

under the Knowledge Transfer Department (KTD).

Subject experts assigned throughoul the company

take the lead in guiding discussions afioui their area

of expertise antl pro\1tle a measure of t|uality assurance regartling the advice given by otiiers. With the

support of KTO personnel, they periodically review

Tech Forum to identify useful threads for storage in

an f)n-line repository. The threatls are extracted, edited, summarized, and assigned keywords. Thus, valuable emergent content is collected and integrated so

that it is widely accessible, easily tli,stributed, and

profitabl)' reused. KTO personnel coniinually monitor

Tech Ft)rum, encourage participation, and provide

entl-user support antl training. The most technically

t|ualified person al each ojieraiing company worldwide is available to offer advice via Tech Forum.

Product developtneni managers use the ft)rum to

offer on-line technical advice to field perstjnnel and

to stay current with api")licLitions issues arising in the

Zack

53

Figure 5

Buckman Laboratories Knowledge Management Architecture

Repository of forum

communication

Acquire

Refine

Post comments

and replies

• By topic

• By author

• By thread

—•-

Store

Review, edit, and

recategonze

PCs and client software

All associates

Distribute

Present

Index by topic,

author, date, and

thread

T

54

1

1

-"»•

Moderated, threaded

discussions

— *

Post

on-iine

— •

Outsourced information service provider

Section leaders, systems operators, technical managers

liultl. Rf.scaivh lihrariims assigiifd to paiticLilar indiistriL'> scartli tor jiuhiiiK a\ailahk- iiiioniiation ahoLit

llK'ii' iiuiu.strie^. An iiiloniiatioii tcchiiolo^tiv gr()ii[)

inaiiiUiin.s IIK' tuchnical iiiha.strin.tLirc.

Discussions

threaded by topic

author, and date

Client software

All associates

knowledge antl the technology infiListiutture. |)ro\ides

a liLie couipetilive advantage.

Context of Knowledge Management

CAi,stoniL-is siaifti liial Bl.s abilits lo k'\x-!a,L;c iis rolIftlixc' kiiowlctiL^c \ ia ']\-c\\ Forum wa^ instriniKMital

in making a sale to tht-ni, liu\\L'\cr, tlic ice'linolo,siy i.s

not jiruiirietary or luading e(.igu; tin- [irocL^ss is nol

L'omplux, The ITLIC .source ol BL's atKantage is not in

tliL' ici,hnology or ihe j^nocess, wiiich aiv ULtsily iinitatetl, iiLit in the cLilture LUKI stiiictLire ot tlie oigani/ation. The organi/ation's willingness to eieate, share,

an(.i ix'apply know Irtlge |>io\idL's the context tor SLICccsstully execLiting BL's knowledge strak'gy ami

aixhitectiiie.

Another reason for ihe tbiiim's success is UKII il has

hecome p a n of the ongoing habits and praciites of

tliL' organization,-' Eveiyone expects his or her

coworkets to reati the toriim legLilai'ly; to p()si prohlems, ie|)lies. and ohseiAaiioiis there: aixi to m n tribiile whenever [)o,ssible. Cxinsisteni. n)lleeli\X' coin[iliance creates antl continLially leint'oixes peixeption

ol ihe toiLim as a reliable LUKI efhtieiit means for

sluiring knowletlge and st>King problems. Ils use.

su[)[>orteti by uttive managemenl of the architecture,

has l)i.'co[iie sell-sustaining BL managemenl Liiitlerstantls iliai ihe t o n t l u e n t e ot i^ulture. lolfs. norms,

habits, antl ])ractices leading to this success is tlifficLili

lo imitate antl, therefcjre, togt'tlier w iih associates'

Zacli

I ha\'e described explicit knowletige, proposetl an

aichitcLtural framewoi'k lor iis management, antl piesentetl iwo examjiles of its application, 'I'liis I'lamework is a toherent apprt)ach t(j begin designing a

tapabilit\ lor managing explicil knowletlge. .Next, I

tlistuss se\er;i! key issLies aboul the bioatier organixalional t^ntext for knowledge management, the

tiesign Lind managemenl of knowietlge-processitig

ac)[")li<.alions. antl the benehts ihat must accrue to be

suttesskil.

Knowletlge LU'chiletinres exist within foLir piimar\

tontexls iliat intUieiue \u)\\ knowletige management

attetts an organization's [leiformante.

ic Cdi/lr.x! atldresses an organi/aiion's intent

LintI abilily to L-X[iloii its knowletlge anil learning

cii[);ibilities better Uuin the competiti(.)n.'~ It inckitles

ilie exient to which the members of an organization

helie\e that supeiior knowledge is a conijietitixe

atUaiitage LUKI how they exfilitiiiy link strategy,

knowletlge. and peift)rmance. 'Ihe successfLiI firms I

lia\e siutlieti aif alile to ai1icLi!ate the link i)etv\een

the slialeg\ •.>{ iheii' organi/atiuii antt what membeis

at all levels of that organization neeti to know, sluue,

antl learn to exetiite that sti ateg\. Lhis articulation

Sloan Management Review

Summer 1999

cs liow thc-y deploy organizational anti leclinological resources antl capabilities ior explicaiinj^ and

leveraging knowl-jdge, which increases ihc probaliility tjf their adtling \ alue.

atldresses the c<)[n|icuii\encss oi

an organization s knowledge. Hxisting knowledge can

be compared to what an organizatitin must kntnv to

execute ils strategy. Wliere there are current <.)r future

gaps, knowledge management efforts shtjuld lie

directed tcmarti (.losing tliem, assuring a strategic

focus. An organization alscj must assess the cjuality and

.strategic value of its knowledge relative to the competition. To the extent that the bulk of a firm's knowledge is common antl basic, tliat knowledge will provide less com[:>elitive atlvantage dian if ihe firiii's

knowledge is Liniquc anti innovaliw, F-xplitating antl

leveraging thai inno\ati\e knowletlge tan pro\itle ihe

greatest competit \ c benefit.

l ontcxi rellects the organization roles

anti striiciurc — brnial and informal — as well as

the .sociocultural factors affecting knt)wietige management such as culiure, power relations, norms, rewartl

.systems, antl management philosophy. Beyond lhe

knowledge manaticment roles prtjposeci earlier, effective knowledge creation, sharing, antl leveraging

requires an orgar izationai climate and rewarti system

that values and encourages cooperation, iriist. learning, anci inno\aiii m antl provities incentives for

engaging in diose knowledge-based roles, activities,

antl proce.sses.-'' I have consistently obsen'etl this

aspect to be a major ob.stacle to effective knowletlge

management.

ci>nlv\l atklresses the existing inf(.)i'niation

lechnology infrasuucture and capabilities supporting

the knowledge nianagement architecture. One adage

states that kntjwlfdge management is 10 percent

technology and SO percent petiple. However, without

tlie ability to seamlessly collect, index, store, Lintl tlistribute explicit knowledge electronically whenever

and wherever ne^-ded, an organizatitjn will not fully

exploit its capahiliues and incentives. As the BL anti

TRI examples ilKstrate, the technology need n()t be

complex or leading edge to provide significant benefit. Its absence, however, would seriously impinge on

the efforts of these companies to effectively manage

their knowledge assets.

New Organizational Roles

The SLiccessful fiinis that I obsenet! have explicitly

Sloan Managemenl Review

Summet 1999

tiefined and rewardeti roles that facilitate knowledge

capture, refinement, retrieval, interpretation, and use.

Perhaps the most important role is that of subjectmatter expert, functicjning as an editor to a.ssure tonality of coiitfHl anti as a repositoiy manager, w ho

assures the t|uality of conttwi by thoughtful abstracting antl indexing. In convening to on-line knowledge

management. TRI found the need for a much greater

investment in editors to perfbrm the.se rt;)les. BL

showetl its ctJinmitment by assigning some of its most

knowletigeahle people to these roles.

Managing Knowledge-Processing Applications

Knowletlge management applications form a continuum frt)m low to high interaction complexity. Forums

are the most interactive and complex application

because they tend to span the entire tacit, explicit

knowledge-processing cycle. Establishing a welldefined social community and shared context to support the use of the technt)lt)gy plays a key role in an

application's success. Electronic pLiblishing. in contrast, is perhaj:)s the mt>st straightforwartL It is oneway distribution of explicit knowledge to a user community that may be loosely affiliated and related cjnly

by its need for access to the .same knowledge reposiloiy, but not neces.sarily supported by a social community. The greater the interaction complexity, the

more that challenges become social, ct)gnitive, and

behavioral in nature rather than technical and, thus,

retjLiire well-managed organizational change (•)rograms.

Knovvletlge rejiositoiies have a life cycle that firms

must manage. Once created, repositories tend to grow,

reaching a point at which they begin to collapse

under their tnvn weight, requiring major reorganizatifin.-'' Their rejuvenatit^n requires deleting obs(.)lete

content, archiving less active but potentially tiseful

content, and reorganizing what remains. Content cjr

topic areas may become fragmented or redundant.

Reorganizing retjuires eliminating those redundancies,

combining similar contributions, generalizing content

for easier reapplication, anti restructuring categories

as needed. SLiccessful knowledge management organizaiions [:)roactively manage and leorganize their

repositories as an ongoing activit)' rather than waiting

for decline to set in before acting.

Complex kntjwledge management problems typically

require multiple repositt)ries segmented by degree of

interactivity, volatility of cf)ntent, or the structure of

the knowledge itself. Each repository may have a different set of (irocesses antl roles b\' which its content

Zack

55

is created, refined, and stored. Ltjng-li\'ed. archival

knowledge may iiave a more formal review anti

approval prticess, w hei'cas Iiesi practices may undergo expcditeti etiiting. anti tiiscussion databases for

rapiti exchange may have no review process other

than after-tlie-fact monittiring by a forum moderaior.

Furthermore, the use of knowledge repositories typically causes knowledge creation and knowlettge

application to become separated in titne and space.

Therefore, firms must continually evaluate the knowietlge to ensure that it applies to c u n e n t context and

56

.

circumstances. Eirms may need to segment their

repositories and their underlying management

processes on the basis of the volcilility of their context as w-ell as content. Eor example, the storage

structures and processes for managing product knowledge in rapitily changing markets may differ significantly from managing that knowledge in stable markets. Segmenting these repositories and identifying

any significant differences in their refinerv' processes

are crucial for successful application, as is their integration to [;)rovitle seamless access to their knov\letlge.

For knowledge repositories to be meaningful, their

structure must reflect the structure of shared mental

models or contextual knowledge tacitly held by the

t)rganization. hi most organizatit)ns, those structures

are neither well defined nor widely shared. Yet their

explication is essential ft)r effectively managing

ex[ilicitiy encotletl organizational knovvietige. This

requires that a firm define what a knov\iedge unit

means anti how to meaningfully index antl categorize

a collecti(3n of knowletlge units fV^r ease of access.

retrieval, exchange, and integration. Creating "semantic con.sensus" even within common practice communities is often a difficult task, let alone across an

entire organization. TRI fotinti developing stantlards

to be a particularly tlifficult challenge, yet o n e that

had to be addressed for the publishing process to

function. Eor example, w h e n TRI first migrated to cjnline pLiblishing, it had no standard spellings for vendor names, technology keywords, or even research

programs — al! essential for effective re|X")sitor\" management. TRI even struggled to create a stantlard and

consistent tiefinition of a knowletlge unit. BL hati

more flexibility within its forums, yet alst) found that

develofiing a meaningful Intlexing scheme for its file

libran' was ciitical for its use. These experiences are

nt)t unusual. Different lexicons naturally emerge from

different parts of an organization. In many ways.

standards are not compatible with the culture of many

organizations. However, the ability to integrate and

Zack

Integration of knowledge across

different contexts opens an organization

to new insights.

share knowledge depends on some broatlly meaningful scheme for its structure.

Integration of knowletlge across different contexts

opens an organization to new insights, A practice

community's exposure to how its knowledge ean be

applied in other contexts increa.ses the scope and

value of that knowledge. Often the variety of experiences within a local community of practice is not

expansive enough tt) fully understand some phenomena. By being able to combine experiences aertjss

communities, the scope of experience is broadened,

as is the ability to learn from those experiences. For

example. 1 worked with a leading imaging firm that

created a stantlarti v\ay to capture and share sales

techniques among ils market segments. By sharing

knowledge of ht)w custt)mers in different market segments used a particular product, salespeople in each

terriujiy were exposed to patterns, itisiglits, and selling opportunities they might not have percei\'ed on

their own.

Benefits Depend on Application

The nature of the benefits gained from managing

explicit knowledge depends on the type of application. Electronic publishing and other icjw interactivity,

high-structure applications tend to provide a significant cost saving ox increased efficiency. Publishing

electronically is much less expensi\'e tiian distributing

t)n paper. In the case of distributetl learning, electronically distributing prepackaged knowledge (e.g.,

electronic texttiooks and ct)urse notes) can save significant travel expenses, in contrast, the more interacti\'e Oi emergent-content applications tend to provide

sup|X)rt for solving problems, innovating, and leveraging opportunities. The greatest impact, however,

comes from combining the two.

For example, BL is adding a distance-learning capability to its other api")licaucjns. roLinding oui its portfolio. The company is poised to reap the greatest benefit by integrating the capabilities of ail \is applicatitins. BL will be able to archive its emergent knowledge (developed through the Tecli Eoaim). make it

available for searching by associates in the field, and

Sloan Management Review

Summer 1399

also ctlit anti rupackagc- tlic- knowledge as training

inaicriaLs hy means of the distance-learning application. Thus, iiainii'g will ha\e more of a "real wtjrld"

feel and focLi.s. SiLidents will lie able to re\iew aetLi;il

[irobleni.s and. afler tleliherating independently, find

real-liTe sokitions. I'ormal trainlnj^ will take place in

lhe field. gi\iiig Mtiidenis the abilily to directly appK'

or integrate the iiaining materials with their own dayto-clay problems. In this way, tho.se materials become

more relevant ami interwoven into the student'.s tacit

experience and the learning more meaningful and

lasting. Ry integn ting the interaciive, emergent forums

\\ ith tht' structurtd content and distribution of formal

training, a firm encourages a continual cycle of

knowledge creati>n and ap|ilication. Tacit kncjwledge

is made explicit \ ia forums, formally transferred \'ia

tlistance learning, and tacitly reapplied in context.

New tacit kn<iwltclge becomes ;i\ailal.")le for sharing

with others via the same cycle. Hach turn of the cycle

increases the kncwiedge of the organization.-' pro\ iding potentially gri-ater competitive advantage.

•

In summaiy, org^inizations that are managing knowledge efk'Cti\ely:

• linclersland iht-ir .strategic knowledge requirements.

• L)e\ise a knowledge strategy appropriate to the

References

• 1. For example, see'

J.S. Brown and P Dugjid, "Organizational Learning

and Communities-of-Pracice' Toward a Unified View

of Working, Learning and Innovation." Organization

Science, volume 2, Februiiry 1991, pp. 40-57;

I Davenport, S. Jarvenpaa. and M. Beers,

"Improving Knowledge Work Processes," Sloan

Management Review, voljme 37, Summer 1996, pp.

53-66:

PF, Drucker, "The New Pniductivity Challenge,"

Harvard Business Review volume 69, NovemberOecemberl991,pp. 69-7li:

B. Kogut and U. Zander, 'knowledge ol ttie Firm,

Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of

Technology, Organization Science, volume 3, August

1992, pp. 383-397,

I Nonaka, "A Dynamic Theory of Organizational

Knowledge Creation," Organization Science, volume

5, February 1994, pp. 14-:!7;

J.B. Quinn, P Anderson, End S. Finkelstein,

"Managing Professional htellect: Making the Most

of the Best," Harvard Business Review, volume 74,

Marchl996, pp. 71-82; a i d

S.G. Winter, "Knowledge and Competence as

Strategic Assets," in D.J Teece, ed.. The

Competitive Challenge: S'rategies for Industrial

Innovation and Renewal (Cambridge, Massachusetts:

Ballinger, 1987), pp 159- 84.

• 2 RJ Heibeler, "Benc marking Knowledge

Management," Strategy ti Leadership, volume 24.

SiDan Management Review

•^iimfflfir 1999

firm's business strategy.

• Imjilement an organizational and technical architecture a|ipropriale to the organizalion's knowledgeprocessing needs.

These factors enable the organization to apply ma.\inuiin eftort antl conitnitnient to creating, explicating,

sharing, applying, and ini[iro\ing its knowledge.

Some \iew knowletlge nuinageinent as merely the

CLinenl business fad. "^'el knowledge is (he essence of

luimans as individuals and collectivities. Respecting

and institutionalizing the role of knowledge and

learning may be the most effecti\'e approach to building a solid and entku'ing competitive tbuntiation for

business organizations. Firms can derive significant

benefits from consciously, proactively. anti aggiessi\'ely managing their explicit and explitable knowledge. Dcjing this in a coherent manner requires aligning a firm's organizational and technical resources

and capabilities with its knowledge strategy. This

rec|uires mapping the firm's organizational and technical capabilities and constraints to its knowledgeprocessing requirements. It may require significant

organizational and technical interventions. The knowledge management architecture pro\-ides a framevvork

for miitlino this eftcjrt.

March-Aprill996, pp. 22-29: and

L.W. Payne, "Unlocking an Organization's Ultimate

Potential Through Knowledge Management."

Knowledge Management in Practice (American

Productivity & Quality Center), volume 1, April-May

19961

• 3 M.H, Meyer and M H Zack, "The Design of

Information Products," Sloan Management Review,

volume 37, Spring 1996, pp. 43-59;

M.H. Zack, "Electronic Publishing: A Product

Architecture Perspective," Information &

Management, volume 31,1996, pp 75-86: and

M.H. Zack and M.H. Meyer, "Product Architecture

and Strategic Positioning in Information Products

Firms," in M,K, Ahuja, D,F Galletta, and H.J,

Watson, eds,. Proceedings of the First Americas

Conference on Infomation Systems (Pittsburgh.

Association for Information Systems, August 1995),

pp. 199-201.

• 4. D.G. Bobrow and A. Collins, eds..

Representation and Understanding: Studies in

Cognitive Science (New York, Academic Press, 1975);

J.S. Bruner. Beyond the Information Given, J.M.

Anglin, ed. (New York: Norton, 1973);

C.W. Churchman, The Design of Inguiring Systems:

Basic Concepts of Systems and Organization (New

York: Basic Books, 1971);

FI Dretske, Knowledge and the Flow of Information

(Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1981);

F Matchlup, Knowledge: Its Creation, Distribution

and Economic Significance. Volume 1: Knowledge

and Knowledge Production (Princeton, New Jersey:

Princeton University Press, 1980); and

D.M. MacKay. Information. Mechanism and Meaning

(Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT Press, 1959).

• 5. F Blackler, "Knowledge, Knowledge Work and

Organizations: An Overview and Interpretation,"

Organization Studies, volume 16, number 6.1995, pp.

1021-1046;

Kogut and Zander (1992);

Dretske (1981); and

J. Lave, Cognition in Frscftce(Cambridge, England:

Cambridge University Press, 1988),

• 6 Brown and Duguid (1991):

J. Lave and E. Wenger, Situated Learning. Legitimate

Peripheral Participation (Cambridge, England:

Cambridge University Press, 1991):

Nonaka (1994);

M. Polyani, The Tacit Dimension [Qarden City, New

York. Doubleday, 1966): and

P. Romer, "Beyond the Knowledge Worker," World

Link, January-February 1995, pp, 56-60.

• 7. J.R Anderson, Cognitive Psychology and Its

Implications {Uevj York: Freeman, 1985): and

R.C, Schanlc. "The Structure of Episodes in Memory,"

in D G. Bobrow and A. Collins, eds.. Representation

and Understanding Studies In Cognitive Science

(New York: Academic Press, 1975), pp. 237-272,

• 8. H Demsetz, "The Theory of the Firm Revisited,"

Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, volume

4, Spring 1988, pp. 141-161, and

R.M. Grant, "Toward a Knowledge-Based Theory of

the Firm," Strategic Management Journal, volume

17, Winter 1996, pp 109-122.

Zack

57

• 9. See, for example, Zack (1996).

• 10 This line of reasoning is addressed in'

Demsetz (19881:

R.M. Grant, "Prospering in Dynamically Competitive

Environments: Organizational Capability as

Knowledge Integration," Organization Science, voiume 7, number 4, July 1996, pp. 375-387:

Kogut and Zander (19921, and

E.T. Penrose, The Theory of the Growth of the Firm

(NewYork. Wiley, 1959)

58

• l i e . Argyris and D.A. Schon, Organizational

Learning- A Theory of Action Perspective (Reading,

Massachusetts. Addison-Wesley, 1978},

T.H Davenport, R.G. Eccles, and L. Prusak,

"Information Politics," Sloan Management Review,

volume 34, Fall 1992, pp. 53-65:

E.H Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership

(San Francisco Jossey-Bass, 1992),

C.J.G. Gersick, "Habitual Routines m TaKk-Performing

Groups," Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes, volume 47, October 1990, pp

65-97: and

P. Nelson and S. Winter, An Fvolutionary Theory of

Economic Change (Cambridge, Massachusetts:

Belknap, 1982)

• 12. R.E. Bohn, An Informal Note on Knowledge

and How to Manage /r(Boston: Harvard Business

School, 1986): and

J. Scfiember, "Mrs. Fields' Secret Weapon," Personnel

Jourrjal, mlumelQ. September 1991, pp. 56-58.

• 13. For an extended discussion of information

product architectures, see

Mever and Zack (19961: and, for an extended discus-

Zack

sion of the refinery aspect, see:

M H. Zack, "An Information Infrastructure Model for

Systems Planning," Journal of Systems

Management, volume 43, August 1992, pp. 16-19

and 38-40.

• 14. MacKay(1969l.

• 15. Meyer and Zack (1996).

• 16. M H. Zack, "Electronic Messaging ancf

Communication Effectiveness m an Ongoing Work

Group," Information S Management, volume 26,

April 1994, pp 23V241.

• 17. Although distributed learning applications are

typically supplemented with electronically published

course materials and assignments Ian integrative

application), distributed learning refers primarily to

the student/instructor interaction (an interactive

application).

• 18 While these approaches are conceptually distinct, they cnutd be implemented within the same

software platform, and, in fact, common technology

will enable smoother integration

• 19.1 obtained this information during twelve

hours of interviews with the senior vice president

responsible for information and consulting services,

the director of information systems strategy responsible for the electronic-publishing project, the lead

application architect, and a senior analyst/consultant

to the project I also reviewed archival documentation that included design documents, a discussion

database used to support the project team, and

related e-mail messages.

• 20 I obtained this information during approximately 100 hours of interviews and focus-group ses-

sions with senior executives and managers of various departments at Buckman Labs

• 21 This company name is a pseudonym

• 22 Buckman Labs has won several awards for its

knowledge management infrastructure, including the

1996 Arthur Andersen Enterprise Award for Sharing

Knowledge and, in 1997, the ComputerWorld/

Smithsonian Award - Manufacturing Section.

• 23 Buckman Labs produces a version of the Tech

Forum for Latin America called Foro Latinumher and

IS translating its forums. Web pages, and other

knowledge repositories into several languages.

• 24. Zack (1994).

• 25 M.H. Zack, "Developing a Knowledge

Strategy," California Management Review, volume

41, Spring 1999, pp 127-145.

• 26. Nonaka (1994), and

M H Zack and J.L McKenney, "Social Context and

Interaction In Ongoing Computer-Supported

Management Groups," Organization Science, volume

6,July-August1995, pp. 394-422.

• Z7. C.C. Marshall, F.M. Shipman III, R.J. McCall,

"Making Large-Scale Information Resources Serve

Communities of Practice," Journal of Management

Information Systems. \iQ\ume 11, Spring 1995, pp.

65-86.

• 28. Nonaka (1994)

Reprint 4034

Copyright © 1999 by the Sloan Management

Review Association.

All rights reserved.

Sloan Uanagemeni Review

Summer 1999