Big Five Correlates of GPA and SAT Scores

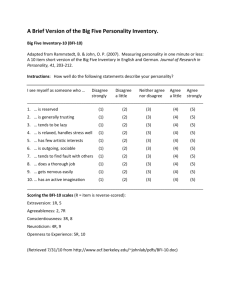

advertisement