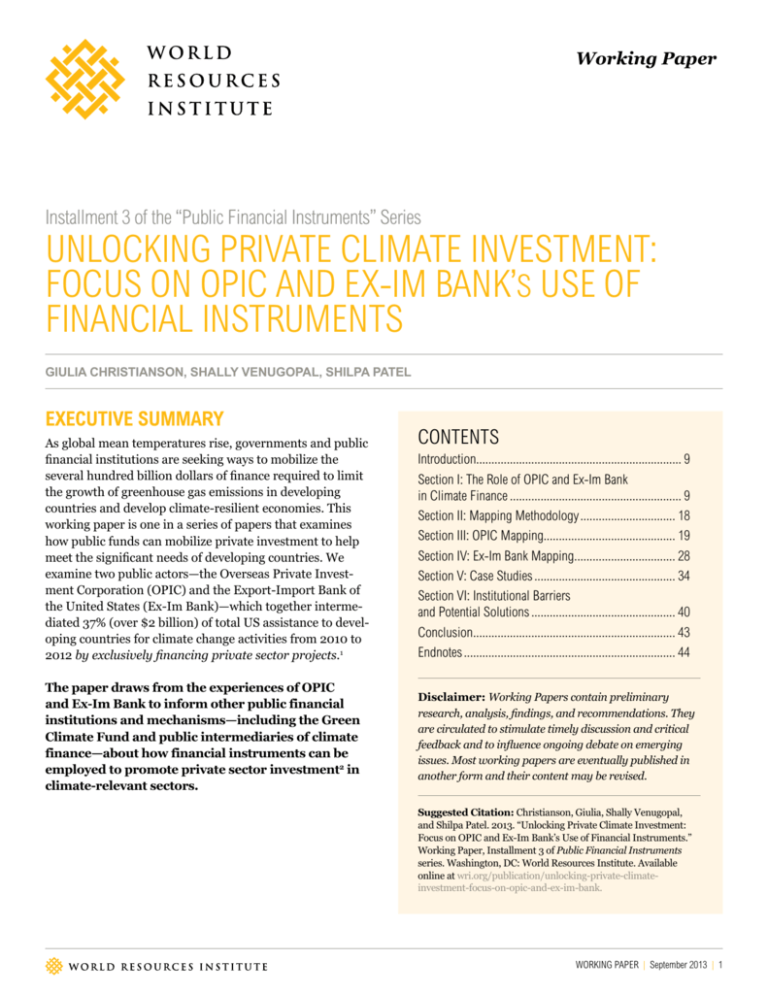

Instruments - World Resources Institute

advertisement