(2015). Early starting, aggressive and - MiNDLab

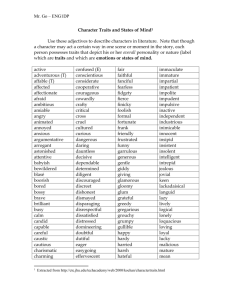

advertisement