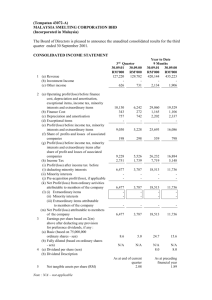

Accounting Panel Seen Curbing Use Of Special Items

Accounting Panel

Seen Curbing Use

Of Special Items

Proposal on ‘Extraordinary’ Credit, Losses

Would Bar Most Use of the Category

-----------------

‘All-Inclusive’ Idea Backed

------------------

By Frederick Andrews

By some accounts, the Accounting Principles Board is about to ban “extraordinary” charges and credits from corporate financial sheets. But Paul B. Lyde, a Florida CPA, doesn’t agree.

Mr. Lyde recently wrote the board that after some effort, he had thought of three business developments possibly allowable as extraordinary items under rules currently before the board:

-The plant facility was smashed by a meteor.

-The sole chemist who knew the secret formula was eaten by a tiger while on a big game hunt.

-The entire board of directors committed suicide, causing loss of public confidence.

The accounting rule makers begin a three day meeting today, with “extraordinary events and transactions” a major item on the agenda. Everyone isn’t as extreme as Mr. Lyde, but it’s generally agreed that the board’s proposed “opinion,” if adopted, would severely curtail special charges and credits. And, authoritative sources say, the board is more likely to cut them out altogether than to weaken it proposal.

“There will be so few extraordinary items,” complains K.D.

Bowes, vice president, finance, at G.D. Scarie & Co., “that the subject becomes academic.”

And it’s high time, too, various accounting critics say. They contend the proliferation of special items has confused investors and enabled corporate managements to gloss over bad business decisions.

Too often, they charge, routine losses are allowed to pile up. Then, when finally written off as an “extraordinary” loss, the write-off is inflated, sweeping all the “garbage” off the books and setting up a healthy profit rebound.

The incidence of extraordinary items has probably doubled since 1967. Almost 40% of the 330 earnings summaries this newspaper printed last week included an extraordinary loss or gain.

The summaries use the shorter label “special.”

As one might guess, charges outnumber credits. A survey of

1,782 companies’ 1971 results turned up about 345 special losses, compared with 315 special gains. The disparity in dollar value is much greater , however. In 1971, the surveyed companies’ special losses totaled $2.35 billion, up form $1.2 billion in 1970 and almost six times the $400 million in 1971 special gains. The gains had increased only moderately form 1970.

Several reasons account for the disparity. For one thing, the bull market in the late ‘60s left a lot of mess to be cleaned up.

Another factor is auditors’ “conservative” bias: When they decide to recognize a loss, they want to go whole hog.

But most important, analysts say, the stock market reacts to net income before extraordinary items. For instance, the price-earnings ratios printed in this newspaper disregard special gains or losses.

The earnings summaries give both per-share versions, but highlight ordinary income.

The so-called “big bath” approach to special write-offs often works: It’s common for a company’s stock to rise after an extraordinary loss is declared.

Many extraordinary items stretch existing accounting rules to the breaking point-or beyond. The principles board’s Opinion 9, adopted in 1966, says flatly that write-downs of inventories, receivables or deferred research and development costs aren’t extraordinary. Yet, companies frequently report them as such.

Added to that is the growing support for an “all-inclusive” notion of earnings. In this view, management is responsible for a concern’s overall financial results, with no distinction between unusual and humdrum. Further, it’s argued, the business world has become much more complex. Once infrequent transactions, such as selling a corporate division, are commonplace. Even “extraordinary” developments, such as expropriations are considered part of the game for multinational concerns.

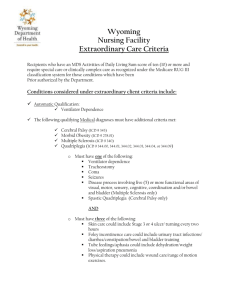

The board’s proposal would change all this by defining an extraordinary item as both “unusual” and “infrequent.” Not only would a business event have to be “clearly unrelated to the

(concern’s) ordinary and typical activities,” but it also couldn’t be

“reasonably expected to recur in the foreseeable future.” Borderline causes would be classed as ordinary.

Further, a company’s “environment” would be considered, including political and geographic factors. What’s unusual for one company might be routine for another. Things like airline skyjackings, product recalls or heavy antipollution costs could often be “ordinary.”

If that language leaves any doubt (and some critics consider it verbiage), the board included a laundry list of items deemed ordinary except in “rare” instances. These include write downs of inventories and receivables; strike effects; foreign exchange gains or losses; sales of capital assets, and cost overruns on long-term contracts. Even the recent dollar devaluation might be considered ordinary.

Indeed, authoritative accounting sources are hard put to say what would remain “extraordinary.” Tax-loss carry forwards would, because another opinion defined them as such. Beyond that, natural disasters might qualify but not always. (Mr. Lyde, the

Florida CPA, doubts the Managua earthquake would make it, inasmuch as earthquakes recur in particular regions.) When oldline concern sold half of its business, that would likely be special, but a conglomerate’s routine wheeling and dealing wouldn’t

The proposed opinion doesn’t lack support. The Securities and

Exchange Commission endorsed it, as did the Financial Analysts

Federation, which would prefer a stiffer version. The Financial

Executives Institute, leading speaker for corporate financial brass, strongly opposes the changes, however. “We emphatically disagree” that present practices are abusive, Charles C. Hornbostel, institute president, declares. But business opposition seems too scattered to have much impact.

Many companies are sharply critical of the proposed rules for the sale of a “business segment” (which would cover any “clearly distinguishable” part of the business). Even if such a sale qualified as extraordinary, the proposed opinion would severely restrict what could be included in the special item. Nothing that would have been written off anyway would qualify, nor would future costs unless directly tied to the disposal, for example, severance pay.

This is meant to prevent a company from setting up an exaggerated reserve and charging expenses to it for years.