Ordinary v. Extraordinary Medical Procedures

advertisement

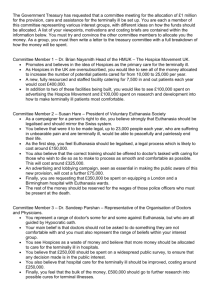

The Consistent Ethic of Life: The Challenge and the Witness of Catholic Health Care Catholic Medical Center Jamaica, New York Joseph Cardinal Bernardin May 18, 1986 II. Ordinary vs. Extraordinary Medical Procedures ... One of the most critical moral questions today is the appropriate use of ordinary and extraordinary medical procedures, especially in the care of the terminally ill. . . . Two fundamental principles guide the discussion. The first is the principle which underlies the consistent ethic: Life itself is of such importance that it is never to be attacked directly. That is why the Second Vatican Council taught: All offenses against life itself, such as murder, genocide, abortion, euthanasia, or willful suicide . . . all these and the like are criminal; they poison civilization. (Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, 31) Consequently, even in those situations where a person has definitively entered the final stages of the process of dying, or is in an irreversible coma, it is not permitted to act directly to end life. In other words, euthanasia—that is, the intentional causing of death whether by act or omission—is always morally unjustifiable. The second guiding principle is this: Life on this earth is not an end in itself; its purpose is to prepare us for a life of eternal union with God. Consistent with this principle, Pope Pius XII, in 1957, gave magisterial approval to the traditional moral teaching of the distinction between ordinary and extraordinary forms of medical treatment. In effect, this means that a Catholic is not bound to initiate, and is free to suspend, any medical treatment that is extraordinary in nature. But how does one distinguish between ordinary and extraordinary medical treatments? Before answering that question, I would like to point out that the Catholic heritage does not use these terms in the same way in which they might be used in the medical profession. That which is judged ethically as extraordinary for a given patient can, and often will, be viewed as ordinary from a medical perspective because it is ordinarily beneficial when administered to most patients. That being said, it is, nevertheless, possible to define, as Pope Pius XII did, what would ethically be considered as extraordinary medical action: namely, all "medicines, treatments, and operations which cannot be obtained or used without excessive expense, pain, or other inconvenience or which, if used, would not offer a reasonable hope of benefit." This distinction was applied by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to the care of the terminally ill in its 1980 Declaration on Euthanasia, which states: When inevitable death is imminent in spite of the means used, it is permitted in conscience to take the decision to refuse forms of treatment that would only secure a precarious and burdensome prolongation of life, so long as the normal care due the sick person in similar cases is not interrupted. In other words, while the Catholic tradition forcefully rejects euthanasia, it would also argue that there is no obligation, in regard to care of the terminally ill, to initiate or continue extraordinary medical treatments which would be ineffective in prolonging life or which, despite their effectiveness in this regard, would impose excessive burdens on the patient. ... . . . the consistent ethic of life will prove useful in such reflection. Here I will limit myself to two observations. First, an attitude of disregard for the sanctity and dignity of human life is present in our society both in relation to the end of life and its beginning There are some who are more concerned about whether patients are dying fast enough than whether they are being treated with the respect and care demanded by our JudaeoChristian tradition. To counteract this mentality and those who advocate so-called "mercy killing," we must develop societal attitudes, policies, and practices that guarantee the right of the elderly and the chronically and terminally ill to the spiritual and human care they need. The process of dying is profoundly human and should not be allowed to be dominated by what, at times, can be purely utilitarian considerations or cost-benefit analyses. Second, with regard to the manner in which we care for a terminally ill person, we must make our own the Christian belief that in death "life is changed, not ended." The integration of such a perspective into the practice of a medical profession whose avowed purpose is the preservation of life will not be easy. It also is difficult for a dying person's family and loved ones to accept the fact that someone they love is caught up in a process that is fundamentally good—the movement into eternal life. In order that these and other concerns may be addressed in a reasoned, Christian manner, the dialogue must continue in forums like this. The consistent ethic, by insisting on the applicability of the principle of the dignity and sanctity of life to the full spectrum of life issues and by taking into consideration the impact of technology, provides additional insight to the new challenge which "classical" medical ethics questions face today. It enables us to define the problems in a broader, more credible context. For the full text of this speech, see http://www.priestsforlife.org/magisterium/bernardinjamaica.html