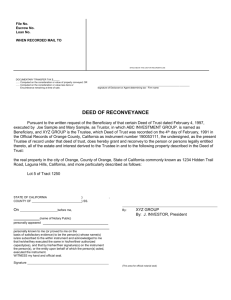

The Corporate Trust Deed under Quebec Law

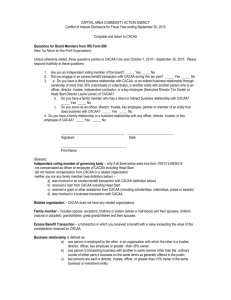

advertisement