Community Building, Civic Capacity

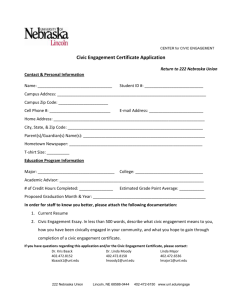

advertisement