Full Article

J. OF PUBLIC BUDGETING, ACCOUNTING & FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT, 26 (2), 313-344 SUMMER 2014

VOLUNTARY ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL

STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING BY ITALIAN LOCAL

GOVERNMENTS

Silvia Gardini and Giuseppe Grossi*

ABSTRACT. The paper focuses on the potential benefits of fair value accounting (FVA) in the public sector and the shift towards the entity theory of consolidation supported by international accounting standards. The analysis of the Italian cases shows neither adjustments of the assets to their fair value, nor any recognition of intangibles other than goodwill in consolidated financial statement (CFS), maintaining the configuration of a municipal corporate group based on historical costs. These findings suggest a lack of focus on FVA by local governments (LGs), which is in contrast with international accounting standards. Using a combination of sources (such as annual reports and interviews), part of this paper is based on multiple-case studies of Italian LGs on the voluntary adoption of CFS.

INTRODUCTION

New Public Management (henceforth NPM) has increased the need for efficiency and effectiveness in the public sector (Osborne &

Gaebler, 1992; Pallot, 1999). This has led to decentralization, externalization and the use of different private and public entities for public service provision (Torres & Pina, 2002; Grossi & Reichard,

2008). As a result, public services previously managed directly by governments are now at both the national and local level provided by

------------------------

* Silvia Gardini, Ph.D., is a Research Fellow at the Alma Mater Studiorum,

University of Bologna, Italy. Her research covers both private and public sector and focuses on international accounting standards, consolidated financial statements and business combinations. Giuseppe Grossi, Ph.D., is a Professor in Business Administration with a focus on Public Management

& Accounting, University of Kristianstad, Sweden. His research focuses on public sector management and governance, crises budgeting, and whole of government financial reporting.

Copyright © 2014 by PrAcademics Press

314 GARDINI & GROSSI private suppliers or by publicly owned corporations. Publicly owned corporations are created in different organizational forms and those with private law legal status can be partially or wholly owned by central or local governments (Grossi & Mussari, 2008).

Furthermore, the provision of public services through market-type mechanisms has increased competition in the public sector

(Reichard, 2006). Moreover, corporatization and agencification have caused fragmentation as well as difficulties for the government to coordinate, steer, and control decentralised entities (Grossi &

Reichard, 2008). According to Christensen and Laegraid (2007, p.

12) "the effect has been to deprive particularly the political but also administrative leadership of levers of control and of influence and information, raising questions of accountability and capacity."

The growing need for financial and political accountability calls for a broader and more complete accounting system (Chan, 2003).

The CFS satisfies both internal and external accountability needs

(Broadbent, Dietrich, & Laughlin, 1996; Martin & Scorsone, 2011).

Moreover, CFSs help improve public sector solvency, sustainability and intergenerational equity. These are some of the reasons for drafting CFSs, which should provide an overview of the financial performance and position, not only of the single government, but also of the publicly owned corporate group (Chan, 2003; Benito, Brusca, &

Montesinos, 2002; Chow, Humphrey, & Moll, 2007). The increasing use of CFS and the growing demand for information and transparency in the public sector (at the central and local level) renders our research particularly interesting.

Local governments in Italy are increasingly using decentralized public, private or non-profit entities to provide public services

(Argento, Grossi, Tagesson, & Collin, 2010; Grossi & Thomasson,

2011). Traditional annual reports disclose only a partial view of the economic and financial activities carried out by local governments as a result of this decentralization. The use of CFS is not yet widespread in Italian local governments and the performance of subsidiaries, joint ventures and associates are not necessarily taken into account.

As a consequence, the financial impact of decentralized activities is not always disclosed to all internal and external users. To date, only a few Italian local authorities are engaged in compiling a CFS. The growing interest shown by different stakeholders, as well as the new standards and early experiences at the local level, demonstrate the

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 315 increasing relevance of CFSs in Italy and are paving the way for future developments (Grossi, 2009).

International accounting standards in preparing CFSs, both for the private and public sector, require recognition in the CFS of the net assets of subsidiaries at their fair value. However, the role of fair value accounting (FVA) appears to be a controversial issue, above all in the public sector, as its benefits for NPM purposes are compromised by limited active market conditions (Bolivar & Galera,

2012).

The aim of this article is to understand the value of FVA in the

CFSs of local governments in the Italian context. The theoretical part of the article highlights the different consolidation theories and methods, the harmonization in the public sector and the consolidation rules and accounting standards in both the private and public sector internationally and in the Italian context. The empirical part instead focuses on the first practices of voluntary adoption of

CFSs by Italian local governments (LGs).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: CONSOLIDATION THEORIES

There are two main theoretical approaches for the preparation of financial reports: the proprietary theory and the entity theory.

Proprietary theory favours the shareholders’ point of view and identifies a company with its owners (Hatfield, 1909; Sprague, 1913;

Husband, 1954; Staubs, 1959). Entity theory gives the company autonomy as a single economic entity, separate from its owners, and favours the business entity’s point of view (Paton, 1922; Paton &

Littleton, 1940; Chow, 1942; Suojanen, 1954, 1958; Li, 1964). In other words, the sources for assets are a company's creditors and its owners. It is thus inevitable that the two different approaches produce different effects on the accounting recognition of economic events and on the accounting process, providing a rather different income and equity configuration (Bird, Davidson, & Smith, 1974;

Ricchiute, 1979; Hendriksen & Van Breda, 1992; Rosenfield, 2005).

The two theoretical approaches significantly impact on the corporate group concept and the consolidation methods.

Consolidation theories concern (a) the choice of the CFS informative function and the most appropriate method of consolidation, (b) the role and recognition in the CFS of minority (non-controlling) interests,

316 GARDINI & GROSSI

(c) the definition of the group of companies’ concept and the consequent identification of the consolidation area (Childs, 1949;

Walker, 1978b).

Proprietary (Ownership) Theory

According to Van Mourik (2010), proprietary theory is an agency concept since “in a traditional agency setting financial reports are prepared by the managers for the purpose of providing information to the proprietors on the basis of which the managers were held accountable for their stewardship. Owners would then release the managers of their responsibility for the results for the past period”

(Van Mourik, 2010, p. 195).

Proprietary theory focuses only on the part that belongs to the parent company, which means that the parent company consolidates only its proportionate share of the assets and liabilities of the subsidiary. The minority interest is not part of the group CFS and is therefore not disclosed in the statements (Alfredson et al., 2009).

According to ownership theory, a company that belong to the parent company must be included in the area of consolidation in proportion to the shares it holds and hence the non-controlling interest is excluded from the CFS. Ownership theory is based on the proportional consolidation method. The proportional consolidation method stresses the ownership interests of the parent company’s shareholders. The CFS is viewed as a modification of the parent company’s financial statements in order to account for the ownership interests of the parent company in other entities (Heald & Georgiou,

2000).

Entity Theory

Under the entity theory, the focus is on the group of companies as an economic “oneness” where the holding company is on the same level as the other companies – the subsidiaries – within the group. The CFS therefore represents the results of the whole group as a single economic reporting unit (Childs, 1949; Walker, 1978b).

Minority interests are a set of financial creditors with more limited rights and powers than the majority’s interests; the two categories, however, have the same level of importance within the group entity

(Taylor, 1996, p. 15). The information needs of all the reporting entity’s stakeholders require particular consideration. A key

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 317 contribution in this direction is provided by Moonitz (1942; 1951) who developed an analysis of entity theory applied to the CFS accounting process while drawing up a map of potential stakeholders such as minority interests, regulatory bodies, short and long-term creditors, the management and stockholders of the dominant company.

The consolidation method is on a full line-by-line basis under the acquisition approach where no distinction is made in equity between majority and minority shares, and the net assets and goodwill of subsidiaries are revalued at their fair value, consistent with the “full goodwill method.” Moonitz (1951, p. 78) stated, “The consolidated assets, debts and net income shown are those of the group as a whole; consequently the consolidated capital shown is that of the entire affiliation.”

The Parent Company Theory and the Parent Company Extension

Theory

Two variations of the main theories have arisen from international accounting practice: the parent company theory and the parent company extension theory (Baxter & Spinney, 1975). From an accounting technique perspective, these are more similar to entity theory, although a part of literature claims they have arisen from proprietary theory (Schroeder, Clark, & Cathey, 2001, p. 483). These additional theories implement a better compromise between the two main theories (Baluch et al., 2010; Kothari & Barone, 2010).

The theories consider the group of companies as a single economic entity but recognize that the single economic entity works primarily in the interests of the parent company and its shareholders.

In this case, the CFS has the function of presenting a picture of the whole group, but from the standpoint of the parent company’s interests. The consolidation method is on a full line-by-line basis under the purchase approach. The identifiable assets and liabilities of the subsidiaries are revalued at their acquisition-date fair value only for the share acquired by the parent company under the parent company approach, or in total under the parent company extension theory. Goodwill recognition and measurement always occur for the portion for which the parent company paid a price (partial goodwill method). Minority interests are computed on a book-value basis and can be entered optionally as a liability, a quasi-liability (between

318 GARDINI & GROSSI liability and shareholders' equity) (Sapienza, 1960, p. 505), or as a component of shareholders' equity. Consistent with the parent company theory, non-controlling interests are traditionally shown as liabilities, otherwise placed within stockholders’ equity.

The parent company concept originates from international accounting practice in drafting CFSs and historically precedes any development of the conceptual financial reporting frameworks by standard setters or jurisdictions. Many standard setters have found inspiration in the parent company theory as a theoretical model of accounting rules for consolidated accounts (e.g., the Financial

Accounting Standard Board FASB , the International Accounting

Standard Board IASB , and the Italian Organismo Italiano di

Contabilità OIC ).

INTERNATIONAL HARMONIZATION AND STANDARDS ON CONSOLIDATION

Harmonization in the Public Sector

In the last decade, under pressure from the New Public

Management paradigm (Hood, 1991, 1995; Jones et al., 2001;

Pallot, 1992; Guthrie & Humphrey, 1996; Guthrie, Olson, &

Humphrey, 1999; Reichard, 2002; Kettl, 2005), most countries around the world have initiated, amongst other things, a series of government accounting system reforms with the aim of improving the accounting information system to support governments in their decision-making process (Guthrie, Olson, & Humphrey, 1999;

Caperchione, 2003; Sciulli, 2004; Pilcher, 2005; Anessi-Pessina et al., 2010). The lack of homogeneity in the implementation of governmental accounting reforms, as documented in some accounting literature (Brusca & Condor, 2002; Pollitt & Bouckaert,

2004; Brusca & Montesinos, 2010), calls for harmonized international accounting standards for the public sector.

While some authors suggest that accounting systems and standards could be the same in both the public and private sectors

(so-called “sector neutrality” of accounting: Micallef & Pierson, 1997;

Anthony, 2000), others tend to criticize this position, pointing out that after some years of enthusiastic adoption of new tools and techniques such as performance measurements, accruals accounting and consolidated financial reporting, these do not appear to have yielded the expected results (Broadbent & Laughlin, 1998; Olson et

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 319 al., 1998; Lapsley, 1999; ter Bogt & van Helden, 2000; Broadbent,

Jacobs, & Laughlin, 2001; Carlin & Guthrie, 2003; Carlin, 2006;

Ezzamel et al., 2007; Ryan, Guthrie, & Day, 2007; Nasi & Steccolini,

2008; Pilcher & Dean, 2009).

Accounting harmonization in the public sector is desirable for reasons relating to the need for comparability of financial information for citizens, for public accounting and auditing professionals, for government institutions. Moreover, in the European context, the need for harmonization in accounting systems is justified by the existence of a common market and the parameters established by the

Maastricht Treaty, which must be respected by European member

States (Benito & Brusca, 2004, pp. 76-77).

In the last ten years, to support these accounting reforms and to achieve accounting harmonization in the public sector, the

International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB), an independent standard setter working under the guidance of the

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), published a set of accounting standards, the International Public Sector Accounting

Standards (IPSASs), specifically for the public sector. The IPSASB strongly encourages the adoption of these standards worldwide, but

IPSASs may not override the general-purpose regulations of financial statements in a particular jurisdiction. This means that the adoption of these standards is determined solely by the jurisdiction of the countries themselves. IPSASs are developed based on IAS/IFRSs and use the same approach in terms of the ultimate financial reporting objective. IPSASs therefore appear to be strongly influenced by business accounting standards and by the Anglo-Saxon approach.

Several international studies have found that IPSASs play a crucial role in international accounting harmonization in the public sector (Benito, Brusca, & Montesinos, 2002; Grossi & Steccolini,

2009; Christiaens, Reyniers, & Rollè, 2010). Several governments and international organizations (such as OECD, NATO, the UN and the

EC) are steering towards full adoption of IPSASs. They have adopted an IPSAS compliant accrual accounting system, which may influence countries around the world to move in this same direction (Grossi &

Soverchia, 2011, p. 527).

320 GARDINI & GROSSI

International Accounting Standards for the Private Sector (IAS/IFRS)

According to the IASB, all entities that control another economic entity shall present CFSs in which the various entities consolidate investments in subsidiaries. This means that all profit-oriented entities are called on to prepare CFSs, regardless of their legal form.

The only possibility of exemption for a parent company is in the case of its sub-holding company status (IASB 2011). Concerning the consolidation procedures, ISFRS 10 par. B86 refers to the content of

IFRS 3 on business combinations, which calls for the application of the acquisition method. In particular, the measurement principle states, “the acquirer shall measure the identifiable assets acquired and the liabilities assumed at their acquisition-date fair values” (IFRS

3, par. 18).

International Accounting Standards for the Public Sector (IPSAS)

According to the IPSASB, the discipline on the compilation of the

CFS by a public sector entity is contained in IPSAS 6. The definition of the scope of consolidation is aligned with that of IFRS 10 and thus the corporate group concept is rather broad and based on a substance-over-form control relationship. Power and benefit conditions lead to determining whether control exists for consolidation purposes.

Concerning the consolidation procedures, IPSAS 6 par. 43 requires the parent company to combine its financial statement with those of the controlled entities by applying a full consolidation method. Any resultant goodwill (or gain from a bargain purchase) is to be accounted for as required by the relevant accounting standard dealing with business combinations. IPSAS 6 also calls for the application of the acquisition method.

National GAAP for the Private Sector

National General Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) for the private sector differ depending on whether the holding company is listed on an EU stock market. If so, IASB accounting standards shall be applied for the compilation of CFSs as required by the Regulation n. 1606/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council.

Otherwise, Italian private sector accounting Legislative Decree

(D.Lgs.) 127/1991 and Italian accounting standard n. 17 provide the rules for the preparation of the CFS. The Italian framework for the

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 321 compilation of CFSs for private sector entities that are not listed on an EU stock market provides a corporate group concept based on a form-over-substance control relationship. The full consolidation method under the parent company approach shall be applied for the controlled entities, and the minority interests are identified in equity or among liabilities (OIC 17, par. 4.3).

The National GAAP for the Public Sector

The new D.Lgs. 118/2011 requires LGs to use uniform accounting rules, under the form of general accounting principles and standards as defined by the Ministry of Finance. Moreover, a specific experimental accounting standard for preparing CFSs is provided in annex n. 4 of the Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers dated 28 Dec 2011 (MEF 4). According to the new law of 2011, the

CFS is mandatory for annual periods beginning on or after January

2014.

To date, national legislation on local authorities (D.Lgs.

267/2000) has not required the mandatory preparation of CFS, although numerous references to the opportunity of providing consolidated financial information can be found in the regulatory text.

In 2008, the former public sector standard setter (Observatory for

Local Government Finance and Accounting founded by the Ministry of the Interior in 2000) approved an experimental standard (PCEL 4) for the CFS, which was not compulsory and was inspired by the IPSASs, since power and benefit conditions were provided similar to those in

IPSAS 6.

The new accounting standard (MEF 4) requires LGs to consolidate controlled entities using the full method. However, the

MEF 4 requires in-house providing companies to be consolidated by applying the proportional method even if the LG controls the in-house providing company.

Fair Value Measurement in the CFS

The IASB theoretical framework has traditionally favoured a group concept and a consolidation method that is more similar to entity theory (Walker, 1978a, p. 310, 1978b). The IASB, in IFRS 3 of

2004, agreed to the parent company extension theory approach requiring the purchase method.

322 GARDINI & GROSSI

The latest version of IFRS 3 dated Jan 2008, with the introduction of the acquisition method, entails a new accounting configuration for business combinations and for the preparation of

CFSs, with the aim of representing the identifiable assets, liabilities and goodwill of subsidiaries at their acquisition-date full fair value.

The difference between the purchase and acquisition methods lies in this function. Although from an operational standpoint the two accounting methods are developed via similar steps, the underlying approaches are fundamentally different. The focus in accounting for business combinations thus changes since a new approach based on entity theory is beginning to emerge. Integration is no longer seen from the parent company’s point of view, instead, a privileged

"outside" view of the group aims at considering it in its entirety. The accounting approach provided by the acquisition method allows this shift to occur (Davis & Largay, 2008; Chen & Chen, 2009).

This move has significant effects on accounting for CFSs. As shown in Table 1, under the full consolidation method, the implementation of the underlying theories presupposes a different intensity in highlighting the amount of the acquisition-date fair value of the net assets and goodwill of subsidiaries. In particular, moving from the parent company theory to the entity theory, the fair value and goodwill amounts recognized in the CFSs increase to their maximum level. At the international level, therefore, a trend is established of including in the CFSs the fair value and goodwill to their full amount.

The Role of Fair Value Accounting: A Critical Issue

The CFS provides a picture of a group of companies as a single economic entity. In doing this, the carrying amount of the parent company’s investment in each controlled entity is eliminated against the parent company’s portion of equity of each controlled entity. The carrying amount of the participation in subsidiaries equals the fair value of the net assets at the acquisition date; the CFS therefore allows defining these values.

The implementation of FVA in the private sector is being discussed widely on an international level, particularly following the

IASB/FASB joint project on reviewing and improving the Conceptual

Framework with the aim of achieving international accounting convergence (IASB, 2005). However, the FVA debate also has its

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 323

TABLE 1

Consolidation Theories and Methods

Proprietary

Theory

Concept of group

Legal extension of the parent company

Primary users

Entity Theory

Single economic reporting unit

Parent Company

Theory

Single economic reporting unit

Parent Company

Extension Theory

Single economic reporting unit

Shareholders of the parent company

Method

Proportional method

Stakeholders of the whole group

Full consolidation under

“acquisition” method

Parent company

Full consolidation under “purchase” method

Recognition of identifiable assets and liabilities

Only parent’s share fair value acquired

100% of the fair value acquired

Only parent’s share fair value acquired

Parent company

Full consolidation under “purchase” method

100% of the fair value acquired

Measurement of Non-controlling interests

NA Fair value basis Book value basis Fair value basis

Disclosure of Non-controlling interests

NA Shareholders’ equity

Liability Quasi-liability/ shareholders’ equity

Intercompany transaction adjustments

Partially eliminated

Eliminated in full

Eliminated in full

(different impact of upstream/ downstream transaction on minority interests)

Eliminated in full

(different impact of upstream/ downstream transaction on minority interests) roots in the past (Moonitz, 1961). More recently, the debate has highlighted two opposite views on the measurement bases for financial reporting: FVA and historical cost accounting (HCA). The contraposition is based on how differently they meet the relevance and the reliability principles in financial statements (Penman, 2007;

Ronen, 2008).

324 GARDINI & GROSSI

The rationale supporting the predominance of FVA (e.g. Barlev &

Haddad, 2003; Bradbury, 2008; Power, 2010) is linked to its greater ability to reflect the true economic substance and the real financial position of the company. This helps avoid any possible manipulations in determining the economic income that HCA could allow, which is due to the fact that FVA is not affected by factors that are specific to a particular entity since it is market-based: “accordingly, it represents an unbiased measurement that is consistent from period to period and across entities” (Walton, 2006, p. 338).

On the other hand, numerous criticisms have been raised against

FVA also by proponents of other alternative measurement bases for financial statements such as deprival value (e.g. Van Zijl &

Whittington, 2006; Whittington, 2010, 2008; Macve, 2010) and replacement costs (Lennard, 2010). Whittington’s attack (2008) against FVA as a universal measurement basis for financial reporting arose from market issues. Markets should provide an independent and objective measure of fair value for assets and liabilities, but they are in fact imperfect, and moreover, information asymmetries persist between the players involved in a business transaction that are able to influence and mislead the assessment of fair value. Precisely for this reason, accounting information needs to exist, since – as stated by Beaver and Demski (1979, p. 40) – in a world with a perfect and complete market, prices are well-know by everyone and therefore “no one would pay an agent to report this measure”, hence, exposing the inadequacy of FVA in an imperfect market (Hitz, 2007; Plantin, Sapra,

& Shin, 2008).

On May 2011, IFRS 13 defined fair value as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or pay to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date”

(IFRS 13, par. 9). This definition emphasizes fair value as a marketbased measurement, setting fair value as an exit price instead of an entry price.

Only a few studies have been conducted in this arena and these focus on the role and appropriateness of FVA as a measurement basis for LG financial reporting for New Public Management purposes.

According to Bolìvar and Galera (2007b), FVA is more appropriate than HCA to assess the solvency and liquidity of a LG. Moreover, FVA could enhance government accountability by increasing the

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 325 transparency of government financial statements and comparability among public organizations. Therefore, FVA implementation in the public sector has a positive effect on understanding government financial statements since “unlike HCA, FVA takes into account current market circumstances to evaluate public sector assets”

(Bolìvar & Galera, 2012, p. 22).

However, empirical results do not clearly lead in this direction when the market conditions necessary for an estimate of fair value are absent. In the presence of a high amount of non-financial assets, such as property, plants and equipment, and in the absence of an active and liquid market for these, FVA has some implementation problems linked to the reliability principle, so that it becomes a measurement with little relevance. The presence of an active and liquid market to measure fair value in a verifiable and objective way is therefore considered crucial for a positive effect on government accountability. Despite the potential benefits of FVA also in the public sector, problems related to the introduction of FVA in this sector essentially relate to the type of assets (financial or non-financial) and to the presence of an active market, which are circumstances that affect the benefits of FVA for the purposes of NPM, and this applies to both transitional and emerging economies (Bolìvar & Galera, 2007a,

2011).

RESEARCH METHOD AND DATA

Research Method

Given these theoretical assumptions, the aim of this paper is to understand the role of FVA in the CFS of local governments in light of the Italian experience. To verify this, two specific research questions are addressed:

RQ1: According to which consolidation theory and method are CFSs compiled in Italian LGs?

RQ2: Is the CFS a stimulus to recognizing the assets of a subsidiary at their acquisition-date fair value?

The decision to focus on the Italian context allows us to observe voluntary behaviour in the preparation of the CFS. LGs that have voluntarily chosen to compile CFSs have had ample discretion in terms of accounting techniques, including the choice of accounting

326 GARDINI & GROSSI standards for the consolidation, the consolidation method and how to allocate the purchase price.

The article is based on multiple-case studies (Yin, 2003) of Italian

LGs on the drafting of the CFS, while the collection of information took place through a combined analysis of documents and semistructured interviews with the Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) of the

LGs. The documental analysis and interviews allowed us to define the state of the art of the implementation of CFSs in Italian local governments and to answer our research questions.

Overview of Cases

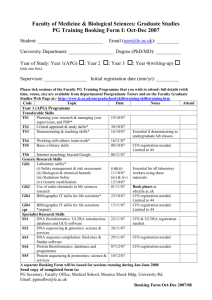

In the last ten years, some LGs have begun to feel the need to experiment with the use of the CFS as a financial reporting tool of the new entity as a corporate group, despite the absence of any ad hoc rules. Consequently, the case studies are voluntary pilot projects in which LGs could choose the most appropriate consolidation accounting standards. Table 2 shows LGs that have experimentally adopted the CFS, highlighting an increase in adoption since 2009.

The list of LGs in descending order by size emphasizes that the first

LGs taking the experimentation path are medium sized (e.g., Pisa), followed more recently by smaller and larger authorities (e.g., Siena,

Torino, Reggio Emilia).

TABLE 2

Timing of Voluntary Adoption of CFS by Italian LGs

LGs Inhabitants

Torino 907,090 -

R. Emilia 170,110 -

Pistoia 90,259 -

Year of publication of CFS

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

- - 2008 2009 2010

- - - 2009 -

Siena 54,634 -

Sesto F. 47,689 - total 1

-

-

2

2007 2008 2009 2010

- - 2009 2010

3 4 6 5

Notes: Source of inhabitants: Istat, Jan. 2011. For reasons of space, “R.

Emilia” and “Sesto F.” are the abbreviation of “Reggio Emilia” and

“Sesto Fiorentino”. This also applies to the following tables.

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 327

The cases were firstly analysed according to five areas of investigation about the technical characteristics of CFSs implemented by Italian LGs. The first refers to the set of accounting standards adopted for the definition of the area of consolidation. This information provides us with an indication on the level of LG openness to the IPSASs (the choice is between Italian private sector accounting standards, Italian public sector experimental accounting standards, IAS/IFRSs, IPSASs). The second area concerns the method used for controlled entities (the choice is between the full method and the proportional method). This information is strongly linked to what is required in the subsequent third area of inquiry on the consolidation theory used as a paradigm for the preparation of the

CFS. The fourth area investigates how to account for differences in consolidation, that are the excess (or deficit) of the purchase price for the subsidiary over the LG’s interest in the subsidiary’s net assets. In the case of excess, the consolidation difference could be recognized as goodwill or loss in income statement, while in the case of deficit, the consolidation difference could be allocated as profit in income statement or equity reserve or contingent liability for badwill. Finally, the fifth area deals with the fair value recognition of subsidiaries in the CFS. The aim is to investigate whether the controlled entities’ assets (both financial and non-financial), intangibles and liabilities were measured at their fair value according to the consolidation procedure.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In all cases, the full line-by-line consolidation method is applied for investments in subsidiaries while the view of the corporate group is consistent with parent company theory, similar to the private sector. Table 3 shows substantial implementation of IPSASs by Italian

LGs. The results show a discrete openness towards the IPSASs world as 4 of 6 LGs implement that set of accounting standards. However, this opening takes place only with reference to the definition of the area of consolidation and not also for the accounting technique of consolidation, as the accounting approach is not consistent with the parent company extension theory provided by the IPSASs. The accounting technique of consolidation implemented, instead, is consistent with the parent company theory, thereby remaining at a less advanced stage with respect to the substance over form principle. Likewise, accounting for differences in consolidation is not

328 GARDINI & GROSSI consistent with the IPSASs approach. In fact, 5 of 6 LGs allow the allocation of the differences in consolidation as equity reserves or directly as loss in income statement, rather than as goodwill or profit in income statement.

TABLE 3

Technical Characteristics of CFSs Implemented by Italian LGs

Area of investigation and Alternatives

1) Accounting Standards for designing area of consolidation

D.Lgs. 127/91 and OIC 17 1

IAS/IFRS 2

IPSASs 3 x 1

0

x x x x 4

PCEL 4 or MEF 4 4 x 1

2) Method of consolidation for controlled entities

Proportional 0

Full x x x x x x 6

3) Theory of consolidation

Proprietary

Parent Company

Parent Company Extention

Entity

4) Accounting for differences in consolidation 5

0 x x x x x x 6

0

0

Goodwill x x 2

Loss in income statement x 1

Equity reserve

Contingent liability for badwill

Profit in income statement x x x x 4

0

0

5) Recognition of subsidiaries' assets at their Fair Value

Yes 0

No x x x x x x 6

Notes: 1 Italian accounting standards for the private sector

(experimental).

2 IAS/IFRS issued by the IASB.

3 IPSAS issued by the IPSASB of the IFAC.

4 Italian accounting standards for the public sector (experimental).

5 Possibility of multiple choice.

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 329

About the FVA for subsidiaries’ assets in CFS, firstly should be noted the significant weight that non-financial fixed assets, as property plant and equipment (PPE) and intangible assets (Int), hold on the consolidated total assets. Based on the latest available CFSs information, Table 4 highlights that PPE represents, on average,

67.34% of the total assets while intangibles represent only a small percentage that amounts on average to 3.96% of the total assets.

The two items together cover over two-thirds of the value of the consolidated total assets.

TABLE 4

Percentage Weight of PPE and Intangibles on the Total Assets

LGs Total Assets

%PPE/total

Torino 12,486,424,000 64.68%

R. Emilia

Assets

1,588,123,861 69.42%

Pistoia 2,035,344,705 59.86%

Pisa 853,340,689 66.82%

Siena 706,730,485 75.17%

Sesto F. 241,076,730 68.07%

Mean 67.34%

%Int/total

Assets

7.95%

1.78%

9.44%

2.07%

0.71%

1.80%

3.96%

%PPE+Int/ total Assets

72.63%

71.20%

69.30%

68.89%

75.88%

69.87%

71.29%

Moreover, Table 5 highlights the LG’s separate financial statements contribution to the CFSs for non-financial fixed assets, like PPE and intangibles, in the latest available CFSs and the contribution from the set of controlled entities, by difference. In particular, an average of 68.93% of the PPE shown in the CFS comes from the LG’s separate financial statement. Accordingly, the contribution from the set of controlled entities is the remaining

31.07%.

About the PPE item, therefore, on average, approximately one third of consolidated total assets comes from controlled entities, and this is the PPE portion that is subject to any revaluation at fair value as a result of the consolidation process, while the portion attributable to the holding would still be recognized in the CFS at the book value basis. About the intangibles item, instead, the contribution coming

330 GARDINI & GROSSI

TABLE 5

Municipality’s Separate Financial Statements Contribution to the

CFSs for PPE and Intangibles

Property, plant and equipment

(Int)

Pisa

Municipal Municip Municipa % total

LGs

Torino

Municipality (M) th/€

Group

(MG) th/€

%

PPE M/

PPE MG ality (M) th/€ l Group

(MG) th/€

%

Int M/

Int MG

Assets subject to FVA

R.

Emilia 713,926

Pistoia

5,318,113 8,075,980 65.85% 5,177 992,764 0.52% 30.00%

232,908 1,218,409 19.12% 528 192,105 0.27% 57.83%

0 17,681 0.00% 19.56%

Siena

0 5,023 6.70%

Sesto F.

199 4,339 3.10%

Mean

68.93% 6.89% 23.80%

Note: The percentages shown in the last column are calculated as follows: [(PPE MG -

PPE M) + (Int MG – Int M)] / total Asset %. It represents the amount of PPE + Int coming from the controlled entities that is subject to revaluation at the acquisition-date fair value. This is the minimum amount on the total Asset that can hide latent surplus as we consider in this piece of analysis only the nonfinancial fixed assets. from the LG’s separate financial statements is very small, on average equal to 6.89%. The formation of this item is due very largely to the contribution of controlled entities and therefore for this item there is a wide margin to operate any revaluations to fair value for the purposes of the consolidation process.

In sum, the process of consolidation would restate at their acquisition-date fair value an average share of 23.80% of the total consolidated assets. However, the cases provide a differentiated margin to play the revaluation (see latest column in Table 4). In some

LGs, generally those of highest size (e.g., Reggio Emilia, Torino), the share of the non-financial fixed assets coming from the subsidiaries subject to the revaluation at their fair value is about 25-30%; in other

LGs of lowest size (e.g., Siena, Sesto Fiorentino), the share of the nonfinancial fixed assets coming from the subsidiaries subject to the revaluation at their fair value drops significantly to about 3-6%. The range of fair value exposure in CFSs (about the non-financial fixed

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 331 assets) is inversely related to the contribution coming from the LG to the formation of the consolidated total assets. The municipal group in which the majority of non-financial assets comes from the LG’s separate financial statement will have less opportunity to highlight the latent surpluses and the fair values. The municipal group in which the majority of non-financial assets comes from the controlled entities’ separate financial statement will have more opportunity to highlight any latent surpluses and the fair values.

In relation to the results about the acquisition-date fair value recognition of the net assets of subsidiaries already shown in Table 2, neither financial assets nor non-financial assets were measured at their fair value. The differences in consolidation remain an indistinct item entered in the balance sheet as goodwill if positive, or within consolidated equity if negative. Accordingly, the surplus the holding company paid is not divided and allocated to assets and liabilities, thus preventing their recognition at the acquisition-date fair value.

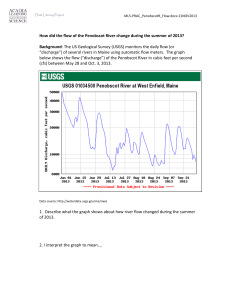

The cases were secondly analysed in order to deepen the specific role of FVA in CFS in the light of the results coming from the fifth area of investigation that deals with the subsidiaries’ assets and liabilities recognition at their acquisition-date fair value. First, we tried to investigate the reasons why no revaluation of assets was made on the occasion of the consolidation process for any of the cases analyzed, although for some of them there were also discrete margins to do so. Second, we tried to grasp the views of CFOs of LGs on the expected potential benefits of FVA in the public sector and in the specific case of the CFS for the municipal group. The information was obtained through the submission of a questionnaire with Likert scale from 1 to 4, in order to verify the degree of agreement / disagreement with the propositions established.

With regard to the reasons leading to the non-recognition of the fair value in CFSs, Figure 1 shows that the failure is neither due to the absence of substantial differences between book values and fair values of subsidiaries’ assets (with the exception of a position in the

“tend to agree” measurement), nor to a specific requirement imposed by the accounting standards applied (with the exception of a position that matches with the entity that has applied the PCEL 4). The motivation is not even due to the possible belief in a limited information usefulness of the fair values (only one position tends to agree with this proposition). All the cases agree that the main reasons

332 GARDINI & GROSSI are linked with the difficulties in estimating fair values and the need to simplify the process of consolidation. The high costs for estimating fair values are also seen as a deterrent to the revaluation process

(only one position is in contrast).

FIGURE 1

Motivation for not Disclose Fair Values in CFSs

Need to simplify the process of consolidation

Not required by the standards applied

Limited information usefulness of fair values

High costs for estimating fair values

Difficulties in estimating fair values

No substantial differences between book values and fair values

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

strongly

disagree tend

to

disagree tend

to

agree strongly

agree

About the CFOs’ opinion on the expected potential benefits of

FVA for CFSs of the municipal group, Figure 2 shows a widespread adherence with respect to propositions proposed, therefore indicating a favored position to the fair values in the CFS. In particular, all entities are in agreement that fair value increases the transparency, the verifiability and the objectivity of the financial results of the municipal group (40% tend to agree and 60% strongly agree). They also consider that fair value provides a picture of the municipal group consistent with the substance over form principle. The belief seems to be less strong, but always so, of the capacity of fair value in order to increase the value relevance of the financial results of the municipal group, in order to provide a more true and fair picture of the municipal group and in order to improve the external reporting in

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 333 supporting the accountability (67% tend to agree and 34% strongly agree). Views differ on the capability of fair value to improve the comparability of the financial results of the municipal group with those of other public administrations. A dissenting opinion is shown that tends to disagree. This happens also about the capability of fair value to improve the internal reporting in supporting the decision making.

FIGURE 2

Potential Benefits of FVA for CFSs of Municipal Group

Increase the value relevance of the MG financial results

Increase the transparency of the MG financial results

Increase the verifiability and objectivity of the MG financial results

Improve the comparability of the MG financial results with those of other public administrations

Provide a more true and fair picture of the MG

Provide a picture of the MG consistent with the substance over form approach

Improve the internal reporting in supporting the decision ‐ making

Improve the external reporting in supporting the accountability

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% strongly disagree tend to disagree tend to agree strongly agree

CONCLUSIONS

Pending international standard-setting switching from a “mixed measurement accounting system” (e.g., lower of cost and market accounting) to a “one-measurement accounting system” with preference for FVA, today the CFS is the financial report where assets and liabilities attributable to controlled entities are recognized at their fair value. This is possible through a different intensity based on the

334 GARDINI & GROSSI accepted consolidation theory (e.g. purchased FV or full FV at the date of acquisition).

In light of the recent debate on the potential benefits of FVA in the public sector to meet the requirements of NPM, such as transparency and accountability (Bolivar & Galera, 2012), and given the increasing attention to CFS, both on a national and international level for local public groups (Grossi, 2009), the research question addressed in this paper is whether the public sector has been paying particular attention to the FVA in the drafting of their CFS.

The analysis of the national case studies enables us to conclude that when the opportunity to depart from HCA is provided and the possibility to restate net assets at their fair value is encouraged, LGs behave differently. In the cases analyzed, no adjustments of assets to their fair value, nor any recognition of intangibles other than goodwill, are made, maintaining the view of the municipal corporate group based on historical costs. This lack of recognition also creates distortion, since the goodwill amount carried on the CFS, together with the equity reserves from the consolidation process, have varying economic implications as this encompasses not only any goodwill but also any intangibles other than goodwill and any surplus value on some assets belonging to the controlled entities. The item therefore becomes insignificant in terms of its understanding and the CFS loses the opportunity to represent the corporate group according to the current market value paid by the parent company to acquire (or establish) it.

The behaviour outlined above concerning the failure to re-assess net assets at their fair value underlies the lack of attention to FVA by

LGs, opting instead for a system that continues to be based on HCA.

The need for FVA in financial reporting as a tool to meet the NPM, hypothesised as advocated by some prior research (Bolìvard &

Galera, 2012, 2011, 2007a, 2007b) does not appear to be confirmed in practice.

However, our results suggest that this failure is not due to a certain lack of confidence in the FVA as a basis for measuring assets, as LGs agree that the fair value plays a crucial role in order to increase the transparency, the verifiability and the objectivity of the financial results of the municipal group, and this is consistent with prior literature. Rather, the non-application of fair value is mainly due to reasons related to the difficulties in estimating fair values and to

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 335 the high costs for estimating it. These difficulties may find their justification in some specific circumstances at least linked to (1) the characteristics of the assets that constitute corporate groups at the local level, which often include large portions of non-financial assets such as property, plants and equipment (e.g., gas and water pipes, and heritage assets), and (2) the absence of an active and liquid market for these specific assets. These features render the quantitative determination of fair value technically difficult. But that is not all. The measurement of fair value in the public sector is not only impossible in certain extreme circumstances, but is also expensive, whether the assessment is implemented in-house or is obtained with the help of external consultants. However, the costs for the measurement of fair value are likely to have inhibited the benefits of

FVA, leading to the conclusion that LGs are compelled to maintain the status quo with regard to HCA.

The results highlighted on the CFS in the Italian cases seem to be consistent with international literature in private and public sector accounting, emphasizing some problems in the FVA application for non-financial assets in an imperfect market world (Beaver & Demsky,

1979; Hitz, 2007; Whittington, 2008, 2010; Plantin et al., 2008;

Bolìvard & Galera, 2012).

Some other critical remarks should be put forward on the current and joint shift in international standard-setting towards an approach to the financial statement that is closer to entity theory and towards fair value measurement. This move has the declared intent of providing information that is relevant and useful for users of financial statements. The concept of the relevance of financial information cannot be separated from the identification of internal as well as external users of CFSs in the public sector (such as politicians, top managers, rating agencies, financial institutions, and especially citizens). This issue cannot be underestimated in a municipal corporate group since citizens in this case are both owners and users of services and in some case also creditors.

Therefore, we believe that this shift, also inevitably required by

IPSASs, should be monitored to assess the effectiveness of the desired benefits for the purposes of NPM. Along with this critical recommendation, further research ideas have emerged on the role of the goodwill item in the public sector. Since municipal corporate groups add value through the supply of public services in accordance

336 GARDINI & GROSSI with minimal economic criteria, without a strong focus on profit, we ask ourselves (a) whether it makes sense to recognize assets at their sale price (in accordance with the new definition of fair value provided by IFRS 13) when they will probably never be sold as a result of their nature, and (b) whether it makes sense to recognize any goodwill amount when the ability to generate future income or cash flows for their own sake clearly cannot be regarded as the main objective of a municipal corporate group.

REFERENCES

Alfredson, K., Leo, K., Picker, R., Loftus, J., Clark, K., & Wise, V.

(2009). Applying International Financial Reporting Standards (2 th ed.). Milton, Qld., Australia: Wiley & Sons.

Anessi-Pessina, E., Nasi, G., & Steccolini, I. (2010). “Accounting

Innovations: A Contingent View on Italian Local Governments.”

Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial

Management, 22 (2): 250-271.

Antony, R.N. (2000). “The Fatal Defect in the Federal Accounting

System.” Public Budgeting and Finance, 20 (4): 1-10.

Argento, D., Grossi, G., Tagesson, T., & Collin, S. (2010). “The

“Externalisation” of Local Public Services Delivery: Experience in

Italy and Sweden.” International Journal of Public Policy, 5 (1):

41-56.

Baluch, C., Burgess, D., Cohen, R., Kushi, E., Tucker, P.J., & Volkan, A.

(2010). “Consolidation Theories and Push-Down Accounting:

Achieving Global Convergence.” Journal of Finance and

Accountancy, 3 (2): 1-12.

Barlev, B. & Haddad, J.R. (2003). “Fair Value Accounting and the

Management of the Firm.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 14

(4): 383-415.

Baxter, G.C. & Spinney, J.C. (1975). “A Closer Look at Financial

Statement Theory.” CA Magazine, 106 (1): 31–36.

Beaver, W.H. & Demski, J.S. (1979). “The nature of income measurement.” The Accounting Review, 54 (1): 38-46.

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 337

Benito, B.L. & Brusca, I. (2004). “International Classification of Local

Government Accounting System.” Journal of Comparative Policy

Analysis, 6 (1): 57-80.

Benito, B.L., Brusca, I., & Montesinos, V. (2002). “The IPSAS

Approach: a Useful Tool for Accounting Reform in Europe.” In V.

Montesinos and J.M. Vela (Eds.), Innovations in Governmental

Accounting (pp. 85-98). Kluver Academic Publishers.

Bird, F.A., Davidson, L.F., & Smith, C.H. (1974). “Perceptions of

External Accounting Transfers under Entity and Proprietary

Theory.” The Accounting Review, 49 (2): 233-244.

Bolivar, M.P.R. & Galera, A.N. (2007a). “The Contribution of

International Accounting Standards to Implementing NPM in

Developing and Developed Countries.” Public Administration and

Development, 27 : 413-425.

Bolivar, M.P.R. & Galera, A.N. (2007b). “Could Fair Value Accounting be Useful, under NPM Models, for Users of Financial

Information?” International Review of Administrative Sciences,

73 (3): 473-502.

Bolivar, M.P.R. & Galera, A.N. (2011). “Modernizing Governments in

Transitional and Emerging Economies through Financial Reporting based on International Standards.” International Review of

Administrative Sciences, 77 (3): 609-640.

Bolivar, M.P.R. & Galera, A.N. (2012). “The Role of Fair Value

Accounting in Promoting Government Accountability.” Abacus, 48

(3): 414-437.

Bradbury, M. (2008). “Discussion of Whittington.” Abacus, 44 (2):

169-180.

Broadbent, J. & Laughlin R. (1998). “Resisting the New Public

Management: Absorption and Absorbing Groups in Schools and

GP Practices in the U.K.” Accounting, Auditing and Accountability

Journal, 11 (4): 403-435.

Broadbent, J., Dietrich, M., & Laughlin, R. (1996). “The Development of Principal-Agent, Contracting and Accountability Relationships in the Public Sector: Conceptual and Cultural Problems.” Critical

Perspectives on Accounting, 7 (3): 259-284.

338 GARDINI & GROSSI

Broadbent, J., Jacobs, K., & Laughlin, R. (2001). “Organizational

Resistance Strategies to Unwanted Accounting and Finance

Changes.” Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1 (5):

565-586.

Brusca, I. & Condor, V. (2002). “Towards the Harmonisation of Local

Accounting Systems in the International Context.” Financial

Accountability & Management, 18 (2): 129-162.

Brusca, I. & Montesinos, V. (2010). “Developments in Financial

Information by Local Entities in Europe.” Journal of Public

Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 22 (3): 299-

324.

Caperchione, E. (2003). “Local Government Accounting System

Reform in Italy: A Critical Analysis.” Journal of Public Budgeting,

Accounting & Financial Management, 15 (1): 110-145.

Carlin, T. & Guthrie, J. (2003). “Accrual Output Based Budgeting

Systems in Australia: The Rhetoric–Reality Gap.” Public

Management Review, 5 (2): 145-162.

Carlin, T.M. (2006). “Victoria’s Accrual Output Based Budgeting

System—Delivering as Promised? Some empirical evidence.”

Financial Accountability and Management, 22 (1): 1-19.

Chan, J. (2003). “Government Accounting: an Assessment of Theory,

Purposes and Standards.” Public Money and Management, 23

(1): 13-20.

Chen, M. & Chen, R.D. (2009). “Economic Entity Theory: Non-

Controlling Interests and Goodwill Valuation.” Journal of Finance and Accountancy, 1 (1): 61-68.

Childs, W.E. (1949). Consolidated Financial Statements. Principles and Procedures . New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

Chow, D., Humphrey, C., & Moll, J. (2007). “Developing Whole of

Government Accounting in the UK: Grand Claims, Practical

Complexities and a Suggested Future Research Agenda.”

Financial Accountability and Management, 23 (1): 27–54.

Chow, Y.C. (1942). “The Doctrine of Proprietorship.” The Accounting

Review, 17 (2): 157–163.

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 339

Christensen, T., & Laegraid, P. (2007). Transcending New Public

Management. The transformation of Public Sector Reforms.

Furnham: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Christiaens, J., Reyniers, B., & Rollè, C. (2010). “Impact of IPSAS in

Reforming Governmental Financial Information Systems: A

Comparative Study.” International Review of Administrative

Sciences, 76 (3): 537-554.

Davis, M. & Largay, J. (2008). “Consolidated Financial Statements.”

The CPA Journal, 78 (2): 26-31.

Ezzamel, M., Hyndman, N., Johnsen, A., Lapsley I., & Pallot J. (2007).

“Experiencing Institutionalization: The Development of New

Budgets in the U.K. Devolved Bodies.” Accounting, Auditing and

Accountability Journal, 20 (1): 11-40.

Grossi, G. (2009). “New Development: Consolidated Financial

Reporting as a Stimulus for Change in Italian Local Government.”

Public Money & Management, 29 (4): 261-264.

Grossi, G. & Mussari, R. (2009). “The Effects of Corporatisation on

Financial Reporting: The Experience of the Italian Local

Governments.” International Journal of Public Policy, 4 (3/4):

268-282.

Grossi, G. & Reichard, C. (2008). “Municipal Corporatization in

Germany and Italy.” Public Management Review, 10 (5): 597–

617.

Grossi, G. & Steccolini, I. (2009). “ IPSAS: Accountability or Colonizing

Tool? The Case of Consolidation .” paper presented at Critical

Management Study 2009 on Accountability and Accounterability,

Warwick, 13–15 July.

Grossi, G. & Soverchia, M. (2011). “European Commission Adoption of IPSAS to Reform Financial Reporting.” Abacus, 47 (4): 525-

552.

Grossi, G. & Thomasson (2011), “Jointly owned companies as instruments of local government: comparative evidences from

Swedish and Italian water sector”, Policy Studies , 32(3), pp. 277-

289.

Guthrie, J. & Humphrey, C. (1996). “Public Sector Financial

Management Developments in Australia and Britain: Trends and

340 GARDINI & GROSSI

Contradictions.” Research in Governmental and Nonprofit

Accounting, 9 : 283-302.

Guthrie, J., Olson, O., & Humphrey, C. (1999). “Debating

Developments in new Public Financial Management: The Limits of

Global Theorising and Some New Ways Forward.” Financial

Accountability & Management, 15 (3/4): 209-228.

Hatfield, H.R. (1909). Modern Accounting: Its Principles and Some of its Problems . New York: D. Appleton.

Helad, D. & Georgiou, G. (2000). “Consolidation Principles and

Practices for UK Government Sector.” Accounting and Business

Research, 30 (2): 153-167.

Hendriksen, E.S. & Van Breda, M.F. (1992). Accounting Theory (5 th ed.). Homewood and Boston: Richard D. Irwin.

Hitz, J.-M. (2007). “The Decision Usefulness of Fair Value Accounting

– A Theoretical Perspective.” European Accounting Review, 16

(2): 323-362.

Hood, C. (1991). “A Public Management for All Seasons?” Public

Administration, 69 (1): 3-19.

Hood, C. (1995). “The “New Public Management” in the 1980s:

Variations on a Theme.” Accounting, Organizations and Society,

20 (2/3): 93-109.

Husband, G.R. (1954). “The Entity Concept in Accounting.” The

Accounting Review, 29 (4): 552-563.

IASB (2005). “Measurement Bases for Financial Accounting –

Measurement on Initial Recognition.” Discussion Paper prepared by staff of the Canadian Accounting Standards Board, November.

Jones, L., Guthrie, J., & Steane P. (2001). Learning from International

Public Management Reform.

Oxford: Elsevier Science.

Kettl, D.F. (2005). The Global Public Management Revolution (2 th ed.). Washington: Brookings Institution.

Kothari, J. & Barone E. (2010). Advanced Financial Accounting: An

International Approach . Financial Times Prentice Hall.

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 341

Lapsley, I. (1999). “Accounting and the New Public Management:

Instruments of Substantive Efficiency or Rationalizing Modernity?”

Financial Accountability and Management, 15 (3/4): 201-207.

Lennard, A. (2010). “The Case for Entry Values: A Defence of

Replacement Cost.” Abacus, 46 (1): 97-103.

Li, D.H. (1964). “The Objectives of the Corporation under the Entity

Concept.” The Accounting Review, 39 (3): 946–950.

Macve, R. (2010). “The Case for Deprival Value.” Abacus, 46 (1):

111-119.

Martin, J., & Scorsone, E.A. (2011). “Cost Ramifications of Municipal

Consolidation: A Comparative Analysis.” Journal of Public

Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 23 (3): 311-

337.

Micallef, F. & Pierson, G. (1997). “Financial Reporting of Cultural,

Heritage, Scientific and Community Collections.” Australian

Accounting Review, 7 (1): 31-37.

Moonitz, M. (1942). “The Entity Approach to Consolidated

Statements.” The Accounting Review, 17 (3): 236-242.

Moonitz, M. (1951). The Entity Theory of Consolidated Statements.

Brooklyn: The Foundation Press Inc.

Moonitz, M. (1961). Accounting Research Study No. 1: The Basic

Postulates of Accounting.

New York, NY: American Institute of

Certified Public Accountants (AICIPA).

Nasi, G. & Steccolini, I. (2008). “Implementation of Accounting

Reforms: An Empirical Investigation into Italian Local

Governments.” Public Management Review, 10 (2): 175-196.

Olson, O., Humphrey, C., & Guthrie, J. (1998). “International

Experiences With “New” Public Financial Management (NPFM)

Reforms: New World? Small World? Better World?” In O. Olson, C.

Humphrey & J. Guthrie (Eds.). Global Warning: Debating

International Developments in New Public Financial Management

(pp. 17-48). Bergen, Norway: Cappelen Akademisk Forlag As.

Osborne, D. & Gaebler, T. (1992). Re-inventing Government.

Reading,

MA: Addison Wesley.

342 GARDINI & GROSSI

Pallot, J. (1992). “Elements of a Theoretical Framework for Public

Sector Accounts.” Accounting, Auditing and Accountability

Journal, 5 (1): 38-59.

Pallot, J. (1999). “Beyond NPM: Developing Strategic Capacity.”

Financial Accountability and Management, 15 (3/4): 419-426.

Paton, W.A. (1922). Accounting Theory.

New York, NY: Ronald Press.

Paton, W.A. & Littleton, A.C. (1940). An Introduction to Corporate

Accounting Standards (Monograph No. 3) . New York, NY:

American Accounting Association.

Penman, S.H. (2007). “Financial Reporting Quality: Is Fair Value a

Plus or a Minus.?” Accounting and Business Research , Special

Issue: International Accounting Policy Forum: 33-44.

Pilcher, R. (2005). “Financial Reporting and Local Government

Reform – A (Mis)Match?” Qualitative Research in Accounting &

Management, 2 (2): 171-192.

Pilcher, R. & Dean, G. (2009). “Implementing IFRS in Local

Government: Value Adding or Additional Pain?” Qualitative

Research in Accounting & Management, 6 (3): 180-196.

Plantin, G., Sapra, H., & Shin, H.S. (2008). “Marking-to-market:

Panacea or Pandora’s Box?” Journal of Accounting Research, 46

(2): 435-460.

Pollitt, C. & Bouckaert, G. (2004). Public Management Reform: A

Comparative Analysis.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Power, M. (2010). “Fair Value Accounting, Financial Economics and the Transformation of Reliability.” Accounting and Business

Research, 40 (3): 197-210.

Reichard, C. (2002). “Marketisation of Public Services in Germany.”

International Public Management Review, 3 (2): 63-79.

Reichard, C. (2006). “Strengthening Competitiveness of Local Public

Services Providers in Germany.” International Review of

Administrative Science, 72 (4): 473-492.

Ricchiute, D.N. (1979). “Standard Setting and the Entity-Proprietary

Debate.” Accounting, Organizations and Society, 4 (1/2): 67-76.

ADOPTION OF THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING 343

Ronen, J. (2008). “To Fair Value or not to Fair Value: A Broader

Perspective.” Abacus, 44 (2): 181-208.

Rosenfield, P. (2005). “The Focus of Attention in Financial Reporting.”

Abacus, 42 (1): 1-20.

Ryan, C., Guthrie, J., & Day, R. (2007). “Politics of Financial Reporting and the Consequences for the Public Sector.” Abacus, 43 (4):

474-487.

Sapienza, S.R. (1960). “The Divided House of Consolidations.” The

Accounting Review, 35 (3): 503-510.

Schroeder, R.G., Clark, M.W., & Cathey, J.M. (2001). Financial

Accounting Theory and Analysis: Text Readings and Cases (7 th ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley.

Sciulli, N. (2004). “The Use of Management Accounting Information to support Contracting Out Decision Making in the Public Sector.”

Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 1 (2): 43-67.

Sprague, C.E. (1913). The Philosophy of Accounts . New York, NY:

Ronald Press.

Staubus, G.J. (1959). “The Residual Equity Point of View in

Accounting.” The Accounting Review, 34 (1): 3-13.

Suojanen, W.W. (1954). “Accounting Theory and the Large

Corporation.” The Accounting Review, 29 (3): 391-398.

Suojanen, W.W. (1958). “Enterprise Theory and Corporate Balance

Sheets.” The Accounting Review, 33 (1): 56-65.

Taylor, P. (1996). Consolidated Financial Reporting. London: Paul

Chapman Publishing Ltd. ter Bogt, H.J., & van Helden, G.J. (2000). “Accounting Change in

Dutch Government: Exploring the Gap between Expectations and

Realizations.” Management Accounting Research, 11 (2): 263-

279.

Torres, L. & Pina, V. (2002). “Changes in Public Service Delivery in the

EU Countries.” Public Money & Management, 22 (4): 41-48.

Van Mourik, C. (2010). “The Equity Theories and Financial Reporting:

An Analysis.” Accounting in Europe, 7 (2): 191-211.

344 GARDINI & GROSSI

Van Zijl, A. & Whittington, G. (2006). “Deprival Value and Fair Value: A

Reconciliation.” Accounting and Business Research, 36 (2): 121-

130.

Walker, R.G. (1978a). Consolidated Statements: A History and

Analysis.

New York, NY: Arno Press.

Walker, R.G. (1978b). “International Accounting Compromises: The

Case of Consolidation Accounting.” Abacus, 14 (2): 97-111.

Walton, P. (2006) “Fair Value and Executory Contracts: Moving the

Boundaries in International Financial Reporting.” Accounting and

Business Research, 36 (4): 337-343.

Whittington, G. (2008). “Fair Value and the IASB/FASB Conceptual

Framework Project: An Alternative View.” Abacus, 44 (2): 139-

168.

Whittington, G. (2010). “Measurement in Financial Reporting.”

Abacus, 46 (1): 104-110.

Yin, R.K. (2003). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (3 th ed.).

CA: Sage Publications.