Persuasion: Proposals and Progress Reports

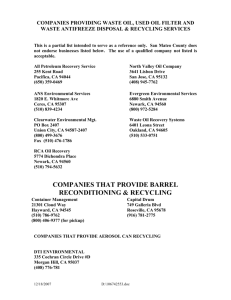

advertisement