The Evolution of Social Commerce

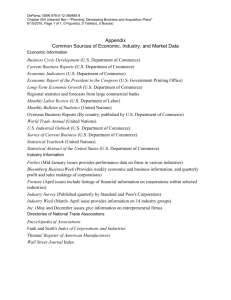

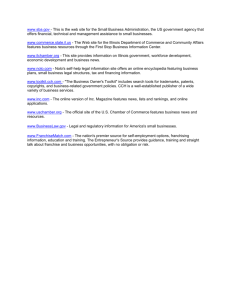

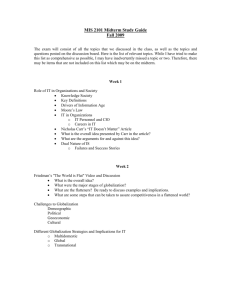

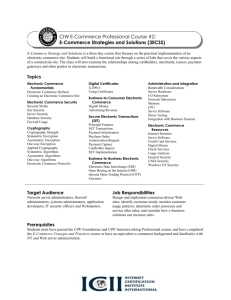

advertisement