how welfare states care

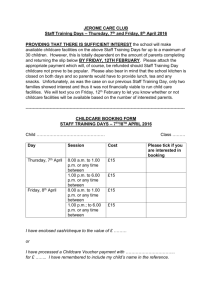

advertisement